Bone stress injuries (BSI) in the young athlete can cause significant time loss, and impact their training at a key developmental phase of bone maturation. Return to play timelines at this age are variable, depending on the site and metabolic potential for the injury to heal, and any associated medical or psychosocial comorbidities. Risk factors for recurrent BSI, or prolonged time loss include relative energy deficiency syndrome (RED-S), eating disorders, metabolic bone disease, and overtraining syndrome. A BSI may also represent a “warning shot” in at risk individuals, that the affected athlete is at risk of low bone mineral density. Given the complexity of medical risk factors, and the potential for a BSI to indicate acute and long-term impacts of athletes; we outline a novel diagnostic pathway to help risk stratify patients in this age group and when to consider further metabolic health work up following a BSI.

Introduction

Bone stress injuries (BSI), are part of a spectrum of overuse injuries that can impact athletes due to repetitive mechanical loading of bone causing structural fatigue and inadequate remodelling. Clinically they are usually detected by localised pain, or swelling (oedema) or radiating pain from common sites that is made worse with loading (1). Imaging modalities such as MRI, can detect early BSI’s, before they develop into a more significant stress fracture, where a cortical defect has now developed and has the potential to develop into a full fracture.

BSI in the young athlete is associated with significant time loss and restriction from training and matches (2). They most commonly occur during periods of intense training demands, and can occur in academy level and elite athletes during their adolescent and early adult years. This period of physical, and biological development occurs alongside two inter-related development landmarks (pubertal growth – peak high velocity) and the development of Peak Bone Mass (PBM). Recent advances in bone scanning, have demonstrated that the adolescent years are a key window for bone health with (90% of bone mineral density (BMD) accrued by age 18), and PBM achieved early in the third decade of life (3).

After an athlete has passed this developmental phase, BMD will decline over adult life with low bone mineral density at this stage a major predictor of long-term (osteoporotic) fracture risk (3). When a BSI occurs, often a key diagnostic challenge for sports physicians is to understand whether this injury is due to explainable acute risk factors (training overload) affecting a single site bone injury with good prognosis, or whether it may part of a wider multisystem presentation (e.g. a relative energy deficiency), sub optimal bone mineral density or a metabolic bone disease. As a sports physician looking after adolescent athletes, there is also a duty of care and ethical obligation to promote long term bone health and to be vigilant of medical conditions, or training environments that may impact athletes long term health.

In view of this, there is a need for a joint-up approach by medical teams looking after young athletes following a BSI. This needs to take into account the clinical features, developmental history, sports specific considerations and appropriate follow up.

Table 1: Considerations for the sports physician when assessing young athletes with a bone stress injury

| Clinical history features to assess | Developmental history features to assess | Sports specific considerations |

| Fracture history

Medication history Mental Health history / disordered eating history Non joint related symptoms – (Bowel, skin, hypothyroidism, anaemia, low iron status, low testosterone – male) Coeliac status Body Mass Index (BMI Smoking/ alcohol status |

Period status for females

Growth trajectory Onset of peak height velocity Pubertal development stage Family history (osteogenesis imperfecta, early onset osteoporosis, parental fracture history) |

Training load

Supplement history Aesthetic or weight based sport requirements Recovery periods Weight bearing or non weight bearing sport. |

Bone stress injuries in young adults

Athletes have an estimated 10% lifetime risk of sustaining bone stress injuries (4), with the incidence in the adolescent athlete population to be between 0.8 to 19% (5–8). Lower limb injuries are the most reported stress fractures with recurrence occurring in up to 22% of cases (9). Recent literature has started to clinically define BSI into (high and low risk injuries), according to a site with return to play timelines reported to be variable (44-155 days) (10). The acute management of BSI has been well defined in the medical literature, based on clinical and imaging scoring tools (11,12), however there is no validated criteria on how we should be investigating the underlying bone health in this population (13).

Clinical follow up pathways after a BSI vary significantly according to the healthcare resources, imaging modalities and clinical expertise available to athletes. There is an understanding that where an underlying medical, nutritional, or metabolic disorder is present, that a longitudinal approach to monitoring bone health is required to reduce the risk of recurrence or low bone mineral density in the future. Measurement of bone mineral density by dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) has traditionally been adopted after fragility fracture in older adults. The use and interpretations of DEXA scans in young athletes however is more nuanced and should only be performed after taking into account a sports specific medical, fracture & clinical history specific to the athlete (14).

There are currently no validated reference values for BMD in athlete populations, with standard DEXA scans reporting bone mineral density for interpretation relative to Z-scores (age/sex matched) or T-scores (30-year-old reference) non athlete populations. Z-score are the preferred reporting values to interpret in athletes <21 years old, but their values must be interpreted with caution (15), and by clinicians with experience in interpreting these. Studies have reported that athletes in weight bearing sports, have approximately 10% higher average total BMD than sedentary controls, and that these increases are higher in specific weight bearing areas such as the femur. There therefore has the potential to underestimate the BMD in this population, if referencing results to standard Z-values in DEXA reports without the training context of the athlete.

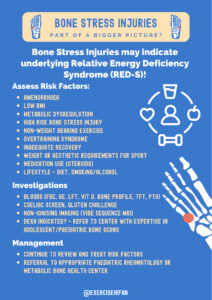

Bone stress injuries – “a warning shot” for Relative Energy Deficiency Syndrome (RED-S)

A bone stress injury may also be the first presentation of an underlying multi-system condition, that is part of a wider relative energy deficiency syndrome, that can impact athlete health and wellbeing. The recent IOC consensus statements on RED-S, have defined key criterion to assess and diagnose RED-S in the athlete, and that are associated with increased risk of BSI (16). These include risk factors for low energy availability such as, amenorrhoea, low BMI, evidence of metabolic dysregulation, high risk bone stress injuries (15). Further exercise related risk factors include, non-weight bearing exercise, overtraining syndrome, inadequate recovery, weight or aesthetic requirements for sport, medication use (steroid equivalent of prednisolone >2.5mg for 3 months), diet and lifestyle factors (smoking status and excess alcohol intake).

Early identification and treatment of these exercise and medical factors can help to safeguard athletes long term bone health (figure 1). A proactive approach to detection of these risk factors in training environments, can help to promote athlete welfare and supervised progression of training loads appropriate for their stage of development, age, and sporting aspirations in the academy of collegiate systems.

Figure 1: Multi-faceted approach to managing an acute bone stress injury

A risk stratification approach to bone stress injuries

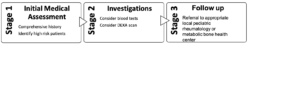

Given that a BSI may either be an isolated injury or part of a wider medical presentation, we propose a pragmatic 3 stage approach to the assessment of BSI in adolescent athletes (figure 2). This pathway consists of an initial medical assessment (stage 1), performed by a sports medicine physician to highlight high risk (diet, medical, fracture history and developmental) risk factors. If indicated then laboratory blood tests +/- assessment of bone mineral density (DXA scan) should be considered (stage 2) , followed by longitudinal follow up and links to local paediatric rheumatology or metabolic bone health centre (stage 3). The proposed pathways include criteria from the: IOC consensus statement on RED-S (16), the paediatric position statement on DXA scanning (14) and clinical reasoning developed in conjunction with paediatric rheumatology bone health experts. (Figure 3).

Figure 2: Pragmatic 3 stage approach to the assessment of a bone stress injury in adolescent athletes

Table 2: Suggested criteria to activate patient referrals from stage 2 to stage 3

| Suggested Criteria for referral to specialist bone centre in athletes with BSI | |

| 1 | History of ≥1 high-risk (femoral neck, sacrum, pelvis) |

| History of ≥2 low-risk BSI (all other BSI locations) within the previous 2 years or absence of ≥6 months from training due to BSI in the previous 2 years | |

| 2 | Lowest Z score ≤ -2 on DXA scan |

| 3 | Family history of osteogenesis imperfecta |

| 4 | Menarche >15 year old or prolonged secondary amenorrhoea |

| 5 | Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (RED-S) identified on Clinical Assessment Tool (CAT2) |

| 6 | Confirmed coeliac disease |

| 7 | Low energy availability (below 30 kcal/kg/Fat Free Mass) |

| 8 | Other co-morbidities/ significant oral glucocorticoid use |

Taking a longitudinal approach to bone health

When a DEXA is performed in athletes, the results should be interpreted in the context of sports specific consideration. The interpretation and results of BMD should be undertaken by clinicians with experience in managing patients following a BSI (stage 3 as outlined above). There is currently no consensus on the use of bone turnover markers (e.g. CTX-1 and P1NP), or their interpretation in athletes, and the use of medications for bone protection is not advised outside of specialist bone centres. Whilst challenging, the identification of low bone mineral density in young athletes provides a window of opportunity to intervene and maximise conditions to achieve an adequate peak bone mass to protects athletes long term bone health.

Multi-disciplinary approach to bone stress Injuries

Making sure that adolescent athletes, achieve appropriate bone health density requires the input and co-ordination of multiple stakeholders. This includes supporting a culture of healthy training environments, where early recognition of medical concerns regarding an athlete from parents or coaches can easily occur. This is particularly important in weight class, aesthetic and non weight bearing sports where the drive to have a competitive advantage, can lead to under fuelling or overtraining.

There is a lack of awareness of nutritional guidance and support reported by some athletes, and coaches, with many reporting that non medical resources such as social media or online content are being used to guide nutritional intake. Inaccurate information, or dogmatic approaches to training that do not factors in recovery or drops in performance as potential indicator for injury are a concern. Medical staff working with athletes must be aware of these pressures, and build in close medical review, monitoring and wellbeing support to promote athlete welfare. These years are a key stage in adolescent development and early warning signs should prompt appropriate investigations for underlying health conditions that may compromise their long-term bone health.

Conclusion

The adolescent athlete presenting to the sport physician with a BSI, presents numerous challenges that need to be addressed in order to manage both their immediate and long-term welfare. In particular, a holistic assessment of the athlete’s overall bone health and investigating any underlying driving factors is crucial. In this paper, we have proposed a novel diagnostic pathway on how to investigate bone health in this specific population, and have provided guidance to health care practitioners on the rationale behind this. By doing so, we hope to improve the standard of care provided to the adolescent population across professional sport.

Authors : Dr Raj Amarnani, Ms Rachel Bower, Mr Ryan Linn, Dr Peter Bale, Dr Irfan Ahmed.

Dr Raj Amarnani

Sport and Exercise Medicine Registrar

UCLH

@DrRajAmar

Ms Rachel Bower

Head Coach Rathbone Amateur Boxing Club

England Boxing Talent Pathway coach

Twitter: @RachelBower6

Ryan Linn

Foundation year Doctor

NHS

Twitter: @Ryan_Linn_

Dr Peter Bale

Consultant Paediatric Rheumatologist

Cambridge University Hospital (Addenbrookes)

Dr Irfan Ahmed

Consultant in MSK, Sport and Exercise Medicine

Twitter : @exerciseirfan

www.mskplaybook.com

Conflict of Interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Competing interests – Nil

Funding – Nil

Ethical Approval – None needed

References

- Song SH, Koo JH. Bone Stress Injuries in Runners: a Review for Raising Interest in Stress Fractures in Korea. J Korean Med Sci [Internet]. 2020 Mar 2;35(8):e38. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32103643

- Goolsby MA, Boniquit N. Bone Health in Athletes. Sports Health [Internet]. 9(2):108–17. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27821574

- Lu J, Shin Y, Yen M-S, Sun SS. Peak Bone Mass and Patterns of Change in Total Bone Mineral Density and Bone Mineral Contents From Childhood Into Young Adulthood. J Clin Densitom [Internet]. 2016;19(2):180–91. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25440183

- Bennell KL, Malcolm SA, Thomas SA, Reid SJ, Brukner PD, Ebeling PR, et al. Risk Factors for Stress Fractures in Track and Field Athletes. Am J Sports Med [Internet]. 1996 Nov 23;24(6):810–8. Available from: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/036354659602400617

- TENFORDE AS, SAYRES LC, McCURDY ML, SAINANI KL, FREDERICSON M. Identifying Sex-Specific Risk Factors for Stress Fractures in Adolescent Runners. Med Sci Sport Exerc [Internet]. 2013 Oct;45(10):1843–51. Available from: https://journals.lww.com/00005768-201310000-00001

- Ekegren CL, Quested R, Brodrick A. Injuries in pre-professional ballet dancers: Incidence, characteristics and consequences. J Sci Med Sport [Internet]. 2014 May;17(3):271–5. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1440244013001783

- Changstrom BG, Brou L, Khodaee M, Braund C, Comstock RD. Epidemiology of Stress Fracture Injuries Among US High School Athletes, 2005-2006 Through 2012-2013. Am J Sports Med [Internet]. 2015 Jan 5;43(1):26–33. Available from: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0363546514562739

- Rizzone KH, Ackerman KE, Roos KG, Dompier TP, Kerr ZY. The Epidemiology of Stress Fractures in Collegiate Student-Athletes, 2004–2005 Through 2013–2014 Academic Years. J Athl Train [Internet]. 2017 Oct 1;52(10):966–75. Available from: https://meridian.allenpress.com/jat/article/52/10/966/112548/The-Epidemiology-of-Stress-Fractures-in-Collegiate

- Beck B, Drysdale L. Risk Factors, Diagnosis and Management of Bone Stress Injuries in Adolescent Athletes: A Narrative Review. Sport (Basel, Switzerland) [Internet]. 2021 Apr 16;9(4). Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33923520

- Hoenig T, Eissele J, Strahl A, Popp KL, Stürznickel J, Ackerman KE, et al. Return to sport following low-risk and high-risk bone stress injuries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med [Internet]. 2023 Jan 31;bjsports-2022-106328. Available from: https://bjsm.bmj.com/lookup/doi/10.1136/bjsports-2022-106328

- Fredericson M, Bergman AG, Hoffman KL, Dillingham MS. Tibial Stress Reaction in Runners. Am J Sports Med [Internet]. 1995 Jul 23;23(4):472–81. Available from: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/036354659502300418

- Nattiv A, Kennedy G, Barrack MT, Abdelkerim A, Goolsby MA, Arends JC, et al. Correlation of MRI Grading of Bone Stress Injuries With Clinical Risk Factors and Return to Play. Am J Sports Med [Internet]. 2013 Aug 3;41(8):1930–41. Available from: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0363546513490645

- Amarnani R, Ahmed I, Fisher C. Bone health in the young athlete – part of the new UK SEM Trainee Blog Series [Blog] [Internet]. British Journal of Sports Medicine. [cited 2022 Apr 20]. Available from: https://blogs.bmj.com/bjsm/2021/12/23/bone-health-in-the-young-athlete-part-of-the-new-uk-sem-trainee-blog-series/

- Skeletal Health Assessment In Children from Infancy to Adolescence [Internet]. International Society for Clinical Densitometry. 2019 [cited 2023 Feb 10]. Available from: https://iscd.org/learn/official-positions/pediatric-positions/

- Hagman M, Helge EW, Hornstrup T, Fristrup B, Nielsen JJ, Jørgensen NR, et al. Bone mineral density in lifelong trained male football players compared with young and elderly untrained men. J Sport Heal Sci [Internet]. 2018 Apr;7(2):159–68. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30356456

- Mountjoy M, Sundgot-Borgen JK, Burke LM, Ackerman KE, Blauwet C, Constantini N, et al. IOC consensus statement on relative energy deficiency in sport (RED-S): 2018 update. Br J Sports Med [Internet]. 2018 Jun 17;52(11):687–97. Available from: https://bjsm.bmj.com/lookup/doi/10.1136/bjsports-2018-099193