Part of the BJSM Knowledge translation series. *This is a plain language translation of a non-BJSM article. Any concerns about the scientific content of the original paper should be directed towards the publishing journal.

Why does this question need to be asked?

Women’s football is booming. Increased professionalism of football clubs, investment and commercial interest continues to drive performance expectations, resulting in a demanding training and match schedule for players. Although injuries rates amongst female footballers are similar to their male counterparts, the proportion of serious injuries is far higher in the female game; leading to significant cost implications.

Whether the menstrual cycle has an influence on injuries occurring in female athletes has long been a subject of scrutiny. Previous studies have demonstrated an increased risk of certain injuries occurring in the late follicular and ovulatory phase of the menstrual cycle; suggesting in particular a greater incidence of ACL injuries, however data has not always been consistent.

This study aimed to assess whether the menstrual cycle phase and extended cycle length had an influence on the incidence of injuries in international footballers

Some brief menstrual physiology

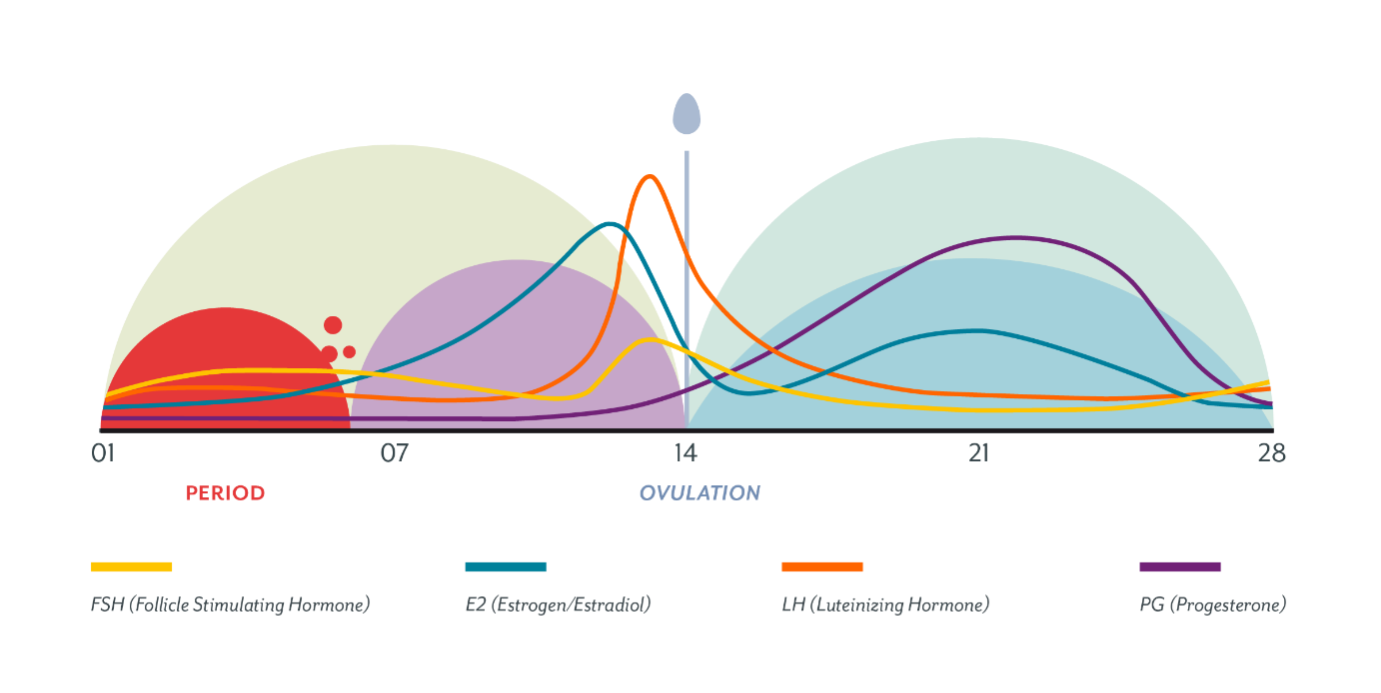

The image above demonstrates the hormonal fluctuations that occur throughout the average menstrual cycle of 28 days (21 -35). The cycle is separated by ovulation at around day 14, into the follicular and luteal phases. Ovulation itself occurs following a surge in LH and oestrogen levels; the 3 days prior to ovulation are deemed the late follicular phase. Extended menstrual cycles are those that are overdue whereupon menstruation is deemed to be ‘late’.

What did they do in this study?

Players from 8 England national squads (Under 15’s-senior level) were recruited for the study. Data was collected over a 4-year period (2012-2016) whilst players were representing their country in either training camps or match play, injuries outside of these periods were excluded. Self-reported menstrual data was provided by players to Football Association support staff at the time of injury. Peak luteal concentration was estimated using a regression equation (Mcintosh et al, (1980)) and injuries in eumenorrheic players were subsequently categorized into early follicular/ late follicular/ luteal phase or delayed menstruation. 156 eligible injuries from 113 players were included in the analysis.

Injury definition: an occurrence which prevented a player from taking part in training or match play for one or more days following the injury.

Exclusion criteria: pre-menarchal athletes, hormonal contraceptive use, self-reported irregular menstrual cycles.

Main findings

- Injury incidence rates (per 1,000-person days) were 47 and 32 % greater in the late follicular phase compared with follicular and luteal phases.

- Data also suggests that muscle and tendon injuries may occur approximately twice as often in the late follicular phase. (muscle rupture, tear, strain, cramps and tendon injuries/ ruptures)

- 20% of all injuries in this study occurred after the expected date of menstruation.

Main limitations

- Participant numbers were relatively small.

- Self-reported menstrual cycle length was used to predict the time in the cycle at which the injury occurred which can be inaccurate (blood tests and ovulation kits would be more precise). A regression equation was used to allocate a menstrual cycle phase.

Take away message – should we be monitoring menstrual cycles to prevent injuries in female athletes?

This study adds further weight to the premise that monitoring athlete menstrual cycles may be useful to identify points within the cycle that athletes are at increased risk of injuries. In particular extended menstrual cycles are easily identified and it may be worthwhile modifying training during this period.

Overall more studies need to be undertaken, with larger participant numbers, more accurate prediction of menstrual data (blood tests/ ovulation indicators) before this research can be used to inform specific exercise practice; further studies will hopefully be able to build on this data and provide further clarification.

Authors and Affiliations:

Dr Emma Jane Lunan @emma_lunan

Sports Physician/ GP/Honorary Lecturer University of Glasgow/SWNT doctor/Chair of Movement for Health

References:

- Martin D, Timmins K, Cowie C, Alty J, Mehta R, Tang A and Varley I. Injury Incidence Across the Menstrual Cycle in International Footballers. Front. Sports Act. Living. 2021 Mar 1;3:616999. doi: 10.3389/fspor.2021.616999. eCollection 2021.

Other content you might enjoy:

McIntosh J. E. A., Matthews C. D., Crocker J. M., Broom T. J., Cox L. W. (1980). Predicting the luteinizing hormone surge: relationship between the duration of the follicular and luteal phases and the length of the human menstrual cycle. Fertil. Steril. 34, 125–130. 10.1016/S0015-0282(16)44894-6 – DOI – PubMed

Fuller C. W., Ekstrand J., Junge A., Andersen T. E., Bahr R., Dvorak J., et al. . (2006). Consensus statement on injury definitions and data collection procedures in studies of football (soccer) injuries. Br. J. Sports Med. 40, 193–201. 10.1136/bjsm.2005.025270 – DOI – PMC – PubMed

Datson N., Hulton A., Andersson H., Lewis T., Weston M., Drust B., et al. . (2014). Applied physiology of female soccer: an update. Sports Med. 44, 1225–1240. 10.1007/s40279-014-0199-1 – DOI – PubMed

Roos K. G., Wasserman E. B., Dalton S. L., Gray A., Djoko A., Dompier T. P., et al. . (2017). Epidemiology of 3825 injuries sustained in six seasons of National Collegiate Athletic Association men’s and women’s soccer (2009/2010-2014/2015). Br. J. Sports Med. 51, 1029–1034. 10.1136/bjsports-2015-095718 – DOI – PubMed

Wojtys E. M., Huston L. J., Boynton M. D., Spindler K. P., Lindenfeld T. N. (2002). The effect of the menstrual cycle on anterior cruciate ligament injuries in women as determined by hormone levels. Am. J. Sports Med. 30, 182–188. 10.1177/03635465020300020601 – DOI – PubMed

Möller-Nielsen J., Hammar M. (1989). Women’s soccer injuries in relation to the menstrual cycle and oral contraceptive use. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 21, 126–129. 10.1249/00005768-198904000-00003 – DOI – PubMed

Chidi-Ogbolu N., Baar K. (2019). Effect of estrogen on musculoskeletal performance and injury risk. Front. Physiol. 9:1834. 10.3389/fphys.2018.01834 – DOI – PMC – PubMed