Exercise remains a key component of rehabilitation for patients recovering from covid-19. However, there is limited guidance on how to start and progress exercise in non-athlete populations in the post-acute period of infection. We discuss if specific “return to exercise” protocols could help to solve this problem and return patients in the general population back to normal function.

Why do we need return to exercise guidance post covid-19?

Current data suggests that the majority of patients will have short (<2 weeks) self-limiting covid-19 infections that are managed in the community by primary care physicians. For a small yet significant number of these patients however, the road to recovery is more protracted, with patients suffering from “long covid”. One symptom study app revealed that at 4 weeks (1 in 7 patients), and 8 weeks (1 in 20 patients) are still suffering from at least one debilitating covid-19 related symptom (1). This includes fatigue, dyspnoea, chest pain, muscle pains, amongst other multisystem symptoms that can last for many months (2).

The burden of these “long covid” symptoms can be significant to patients, both physically and economically, as many patients are left unable to work, and at risk of losing their livelihoods. In the absence of clear guidance on safe rehabilitation and how to return to exercise, many first contact practitioners are left advising patients to undertake periods of prolonged rest, which risks physical deconditioning. This is particularly important for patients with pre-existing Long-Term Conditions (LTC) or those living in low/middle income countries disproportionately affected by covid-19 due to fewer healthcare resources (3).

We propose that new “return to exercise” guidelines for the general population (non-athletes) are needed to help return patients back to full function and prevent long term disability post covid-19 infection (4). This will require a shift in perspective from medical and non-medical stakeholders to prioritise rehabilitation alongside survivorship and rapidly expand our existing capacity to supervise physical rehabilitation in the community.

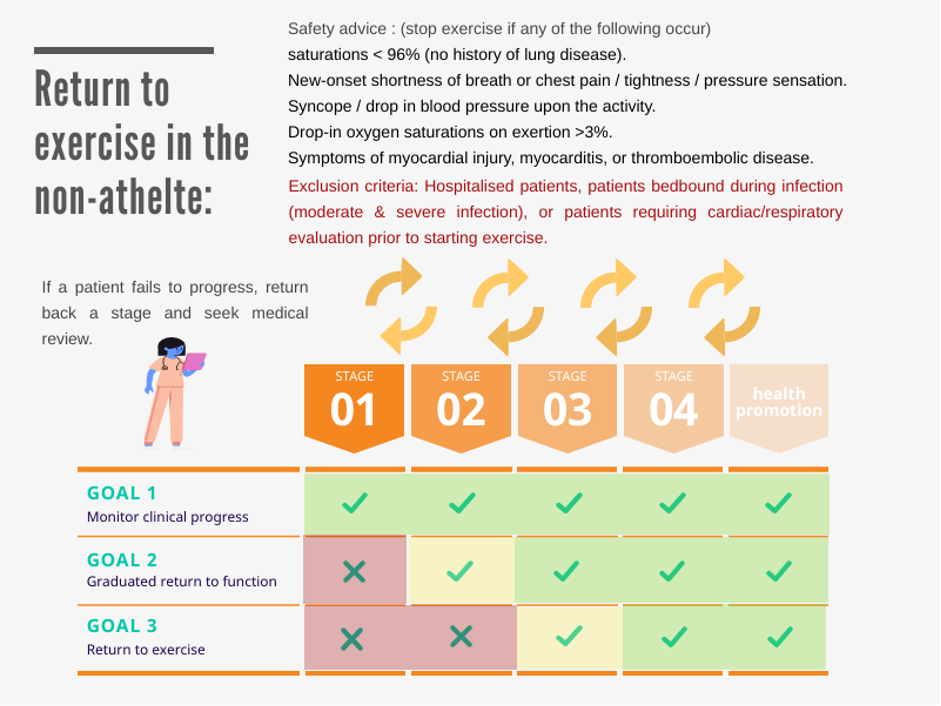

Figure 1. Illustration of the return to exercise model in the non-athlete including safety advice and exclusion criteria.

Return to exercise model

We propose a draft version of a 5-stage protocol to assist clinicians in returning patients to exercise. This protocol aims to bring together time and progress-based intervals during rehabilitation, alongside holistic advice to address; sleep, nutrition, social support strategies, and mental health complaints. Due to the complexity of rehabilitation needs in some subgroups of patients, we propose that the following groups of patients be excluded from the return to exercise protocol:

- Patients hospitalised, or bedridden during the course of illness (moderate and severe illness).

- Patients on long term oxygen, or who require cardiac / respiratory evaluation prior to starting exercise.

Challenges

- We currently have limited data on the clinical course of recovery in patients with mild covid-19 illness. (5)

- Some patients may have prolonged rehabilitation needs in the community for up to 3-6 months after recovery from covid-19 (1,2,6).

- Primary care physicians responsible for managing post covid-19 patients may not have direct access to rehabilitation services, or access to urgent cardiac or respiratory investigations.

- Currently, the majority of suspected covid-19 infections are diagnosed based on symptoms alone due to a lack of PCR swab testing in the community.

- Comprehensive guidelines currently exist for “return to sport” in professional athletes (7), and military personnel (8), but not for non-active patients in the general population.

| Table 1 – NICE & SIGN recommended time-based criteria for defining patients with persistent COVID symptoms (5). | ||

| <4 weeks duration | 4-12 weeks duration | >12 weeks duration |

| Acute phase | Ongoing Symptomatic Phase | Post COVID Syndrome |

Table 1. NICE

Solutions

- The rehabilitation and “Return to Exercise” guidance should focus on activities of daily living (ADL), return to function, and then exercise.

- “Return to Exercise” guidelines are likely to adopt a more cautious and prolonged timeline in non-athletes, which takes into account their baseline health, premorbid function, rehabilitation and occupational needs.

- For complex or protracted rehabilitation needs, a regional multi-disciplinary team (MDT) rehabilitation service could be provided via referral (9). The MDT would provide input from SEM, physiotherapy, OT, rehabilitation, respiratory, and cardiology physicians.

- Exercise clinicians may be able to offer unique skills and help act as a “quarter back” to co-ordinate individualised rehabilitation plans for patients (10). This could involve undertaking biomechanical assessments, prescribing exercise and reviewing patients holistically in a multisystem approach.

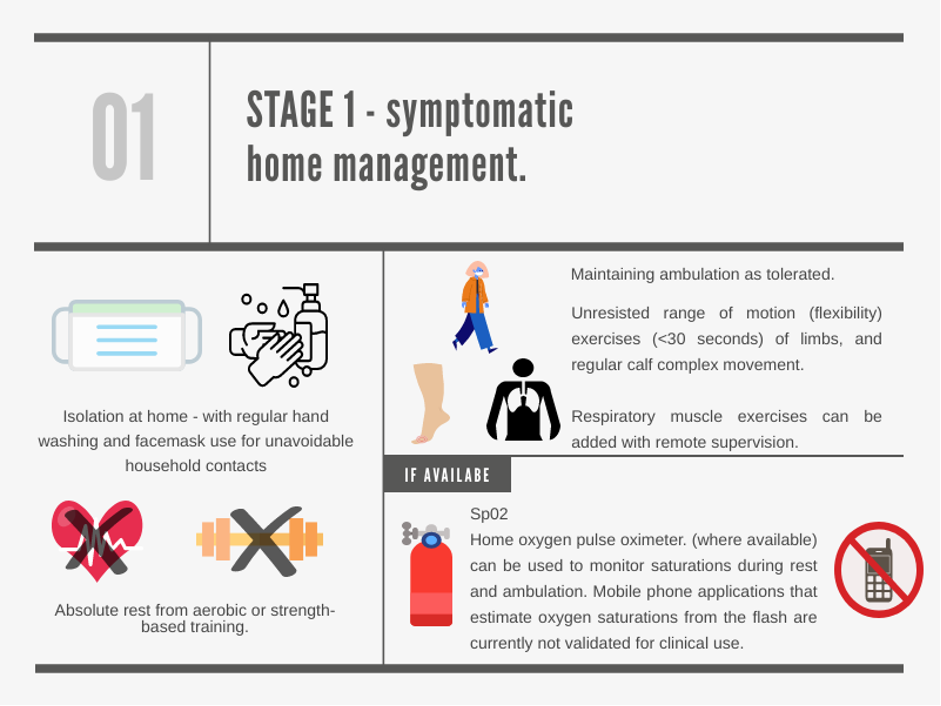

Stage 1 – Rest from exercise

- All exercises focused on aerobic or strength training should stop whilst patients are symptomatic in the acute phase of infection.

- Where available, pulse oximetry can help to guide ambulation, though oxygen saturation monitors on phones are not yet validated for clinical use. (2,11).

- Controlled and paced breathing techniques can be used to aid ambulation and ease breathlessness (12).

- Hygiene measures are advised to prevent indoor transmission of the virus to close contacts (<6 feet) (13). There have been several outbreaks in care homes, collegiate and university campus facilities where communal areas are utilised (14).

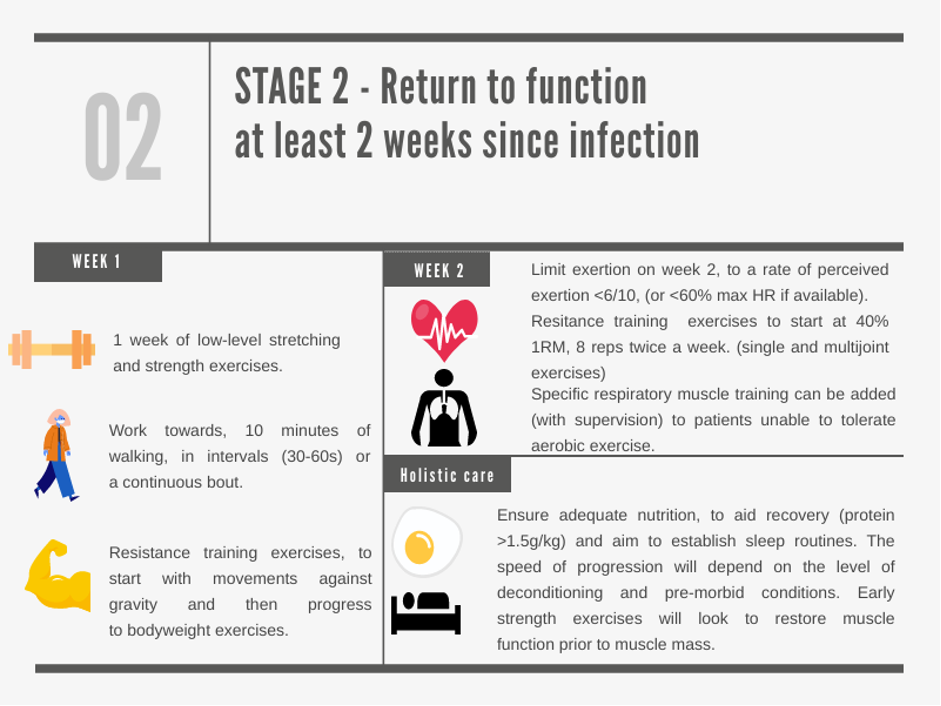

Stage 2 – Graduated return to function

- Initially, limit aerobic exercise to walking and carrying out ADL’s. Begin low level stretching and strength exercise; flexibility and strength exercises can minimise further physical deconditioning (8,9).

- Gradual increase in aerobic exercise, limited to 6/10 on a scale of rate of perceived exertion, and strength exercises up to 40% one repetition maximum (1RM) beginning with bodyweight exercises (7,17). Even modest improvement in fitness can reduce symptoms of breathlessness and can aid recovery post covid-19 (12).

- For patients who are unable to tolerate aerobic exercise due to respiratory muscle weakness, or chronic lung disease consider referral for specialist pulmonary rehabilitation or supervised respiratory muscle training.

- Consider targeted nutritional interventions (caloric supplementation or protein intake >1.5 k/kg) in high risk groups. These include patients at risk of a catabolic state, who are elderly, frail or exhibit sarcopenia (15).

Stage 3 – Graduated return to exercise

- Increase volume of aerobic exercise with shorter intervals (30-60s) or continuous bouts of exercise working toward the WHO recommended levels of physical activity (16).

- Aim to increase muscle strength as well as function; resistance training load can be increased gradually up to 70% of 1RM (8-12 reps, 2-3 sets) to increase muscle strength (17).

- Progression may take longer for patients who have a low baseline fitness (premorbid condition) or whom demonstrate significant post infection deconditioning. Consider referral to a regional MDT rehabilitation clinic where available in secondary care (6).

- Where available, pulse oximeters and heart rate responses to exercise can be used alongside ratings of perceived exertion to monitor exercise intensity.

Stage 4 – Health promotion and patient centred goals

- Patients at risk of significant deconditioning, such as those who were bedbound, may benefit from an individualised exercise prescription or secondary care input to prevent further deconditioning (18).

- Exercise programs online or via apps may be used to promote continued physical activity and improve motivation through progress tracking. Group based exercise may also be delivered online and increase motivation when exercising at home (12).

- Consider screening high risk patients to identify risk factors such as obesity, sarcopenia or frailty. Targeted interventions such as exercise prescription, nutritional supplementation, or specialist physiotherapy may improve long-term outcomes.

- Covid-19 may adversely affect the mental health of patients both directly and indirectly (19, 20). If appropriate, offer psychological support, sleep hygiene interventions and consider referral to psychological services through local pathways.

Key points

- There is limited guidance available on how to return non-athlete patients to exercise post covid-19.

- “Return to Exercise” guidelines for non-athletes may help to prevent physical deconditioning and reduce disability post covid-19.

- Patients with prolonged symptoms (“long covid”), or who fail to progress during a “return to exercise” protocol may benefit from an MDT approach to rehabilitation.

- Exercise physicians could play a key role, in initiating and supervising structured exercise programs for patients with complex rehabilitation needs.

Authors and Affiliations:

Dr Aessa Mahmud Tumi1, Dr Irfan Ahmed2

Corresponding authors email : aessa.tumi@nhs.net. Twitter: @Aessa_Tumi

- Dr Aessa Tumi – GP Trainee on the St Mary’s VTS, London. He has an interest in musculoskeletal, sport & exercise medicine.

- Dr Irfan Ahmed – Sport & Exercise Medicine Registrar and General Practitioner

References:

- Long Covid: Who is more likely to get it? [Internet]. BBC News. 2020 [cited 21 October 2020]. Available from: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/health-54622059

- Greenhalgh T, Knight M, A’Court C, Buxton M, Husain L. Management of post-acute covid-19 in primary care. BMJ. 2020;:m3026.

- Carter C, Thi Lan Anh N, Notter J. COVID-19 disease: perspectives in low- and middle-income countries. Clinics in Integrated Care. 2020;1:100005.

- Do we need new COVID-19 specific ‘return to exercise’ protocols? | BJSM blog – social media’s leading SEM voice [Internet]. BJSM blog – social media’s leading SEM voice. 2020 [cited 29 September 2020]. Available from: https://blogs.bmj.com/bjsm/2020/09/13/do-we-need-new-covid-19-specific-return-to-exercise-protocols/

- https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/gid-ng10179/documents/final-scope

- Faghy M, Ashton R, Maden-Wilkinson T, Copeland R, Bewick T, Smith A et al. Integrated sports and respiratory medicine in the aftermath of COVID-19. The Lancet Respiratory Medicine. 2020;8(9):852.

- Wilson M, Hull J, Rogers J, Pollock N, Dodd M, Haines J et al. Cardiorespiratory considerations for return-to-play in elite athletes after COVID-19 infection: a practical guide for sport and exercise medicine physicians. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2020;54(19):1157-1161.

- Barker-Davies R, O’Sullivan O, Senaratne K, Baker P, Cranley M, Dharm-Datta S et al. The Stanford Hall consensus statement for post-COVID-19 rehabilitation. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2020;54(16):949-959.

- Nabavi N. Long covid: How to define it and how to manage it. BMJ. 2020;:m3489.

- NIHR Evidence – Living with Covid19 – Informative and accessible health and care research [Internet]. Evidence.nihr.ac.uk. 2020 [cited 17 October 2020]. Available from: https://evidence.nihr.ac.uk/themedreview/living-with-covid19/

- Question: Should smartphone apps be used clinically as oximeters? Answer: No. – CEBM [Internet]. CEBM. 2020 [cited 30 September 2020]. Available from: https://www.cebm.net/covid-19/question-should-smartphone-apps-be-used-as-oximeters-answer-no/

- Support for Rehabilitation: Self-Management after COVID-19 Related Illness [Internet]. WHO. 2020 [cited 25 September 2020]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/support-for-rehabilitation-self-management-after-covid-19-related-illness

- How COVID-19 spreads [Internet]. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2020 [cited 21 Sep 2020]. Available from:https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/how-covid-spreads.html

- About 40 universities report coronavirus cases [Internet]. BBC News. 2020 [cited 29 September 2020]. Available from: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-54322935

- Caccialanza R, Laviano A, Lobascio F, Montagna E, Bruno R, Ludovisi S et al. Early nutritional supplementation in non-critically ill patients hospitalized for the 2019 novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19): Rationale and feasibility of a shared pragmatic protocol. Nutrition. 2020;74:110835.

- Bull FC, Al-Ansari SS, Biddle S, et al. World Health Organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. British Journal of Sports Medicine 2020;54:1451-1462.

- Kravitz L. DEVELOPING A LIFELONG RESISTANCE TRAINING PROGRAM. ACSMʼs Health & Fitness Journal. 2019;23(1):9-15.

- After-care needs of inpatients recovering from COVID-19 [Internet] NHS England. 2020 [cited 29 September 2020]. Available from: https://madeinheene.hee.nhs.uk/Portals/0/C0705_Aftercare%20needs%20of%20inpatients%20recovering%20from%20COVID-19_3Aug%20-%20Copy.pdf

- Serafini G, Parmigiani B, Amerio A, Aguglia A, Sher L, Amore M. The psychological impact of COVID-19 on the mental health in the general population. QJM: An International Journal of Medicine. 2020;113(8):531-537.

- Rogers J, Chesney E, Oliver D, Pollak T, McGuire P, Fusar-Poli P et al. Psychiatric and neuropsychiatric presentations associated with severe coronavirus infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis with comparison to the COVID-19 pandemic. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(7):611-627.