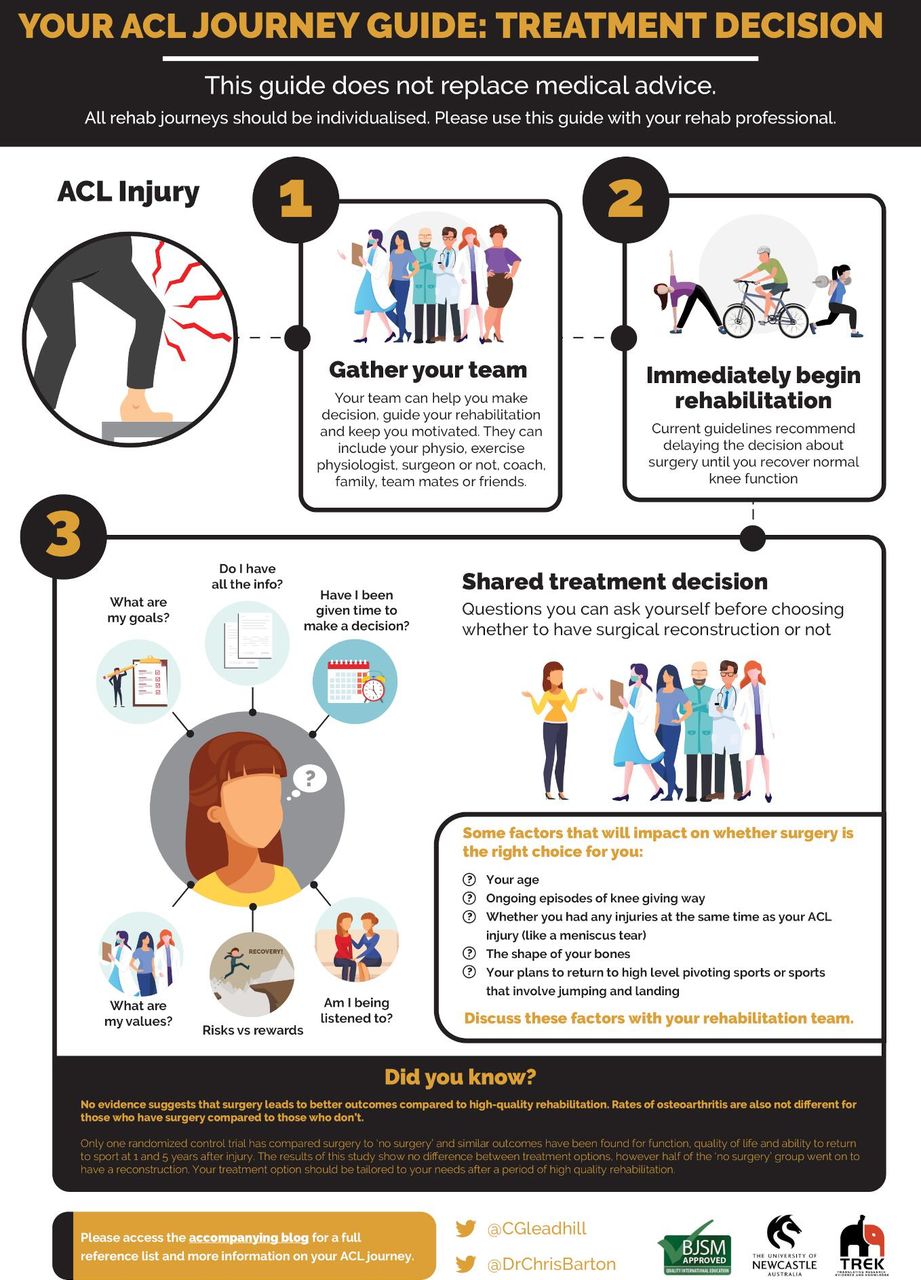

This blog accompanies two infographics – published in British Journal of Sports Medicine – presenting the best available evidence, and designed with input from people who have experienced ACL injury. Both authors of the infographics are clinicians and researchers who work with many people of all ages and levels of sport after ACL injury. These infographics are designed to be used with your health professional, help guide your decisions and rehabilitation process.

Part 1: Treatment decision

Gathering your rehab team

After an ACL injury, it is common to feel angry, depressed, frustrated and uncertain about your future (1). First, you should gather members of your rehab team to help you make decisions, guide your rehabilitation and keep you motivated. Members of your team can include exercise professionals (e.g. physiotherapist), a surgeon, a sports doctor, your coach, team-mates, your family, and your friends.

Starting rehabilitation straight away

You should begin high-quality rehabilitation immediately after an ACL injury (2). Most experts agree that after your ACL injury, the best course of action is to try to return normal knee function and delay the decision about whether to have surgery or not until after a period of rehabilitation (3).

Deciding whether to have surgery (or not)

Younger, more active patients are more likely to re-injure their knee but this is probably unrelated to whether you have surgery or not (4, 5). Returning to high level pivoting sports is associated with more risk than running in straight lines, for example. Having other knee injuries, like meniscal tears, at the same time as your ACL injury is associated with worse outcomes but again the choice about surgery doesn’t seem to impact this outcome (6, 7). However, some injuries may need to be repaired and this will be an individual decision. It is important to discuss factors like your age, other injuries and your plans to return to high level pivoting sports because you can talk with your rehabilitation team how to reduce your future injury risk (8). Remaining happy, healthy and active is a key consideration for anyone following ACL injury and this may or may not involve surgery.

There is no clear evidence that surgery is superior to undertaking high quality rehabilitation alone. There is only one published randomised trial comparing the two options (9). This reported no difference in pain, function or return to pre-injury activity levels at 1-, 2- and 5-years after an ACL injury (9). Current evidence suggests that, in the long-term, there is no difference in how many people develop osteoarthritis between people who have their ACL surgically reconstructed and people who don’t have surgery (10). It is clear that some people can cope without surgery following an ACL injury (9,10). Some people may even be able to return to high level pivoting sports without an ACL reconstruction (11). We recommend you think about the following things when talking to your rehab team and making your decision:

- Do I have all the information?

- What are my goals?

- What are my values? (Time with kids, playing with friends)

- What are the risk versus rewards for having surgery now?

- Am I being listened to?

- Have I been given enough time to make this decision?

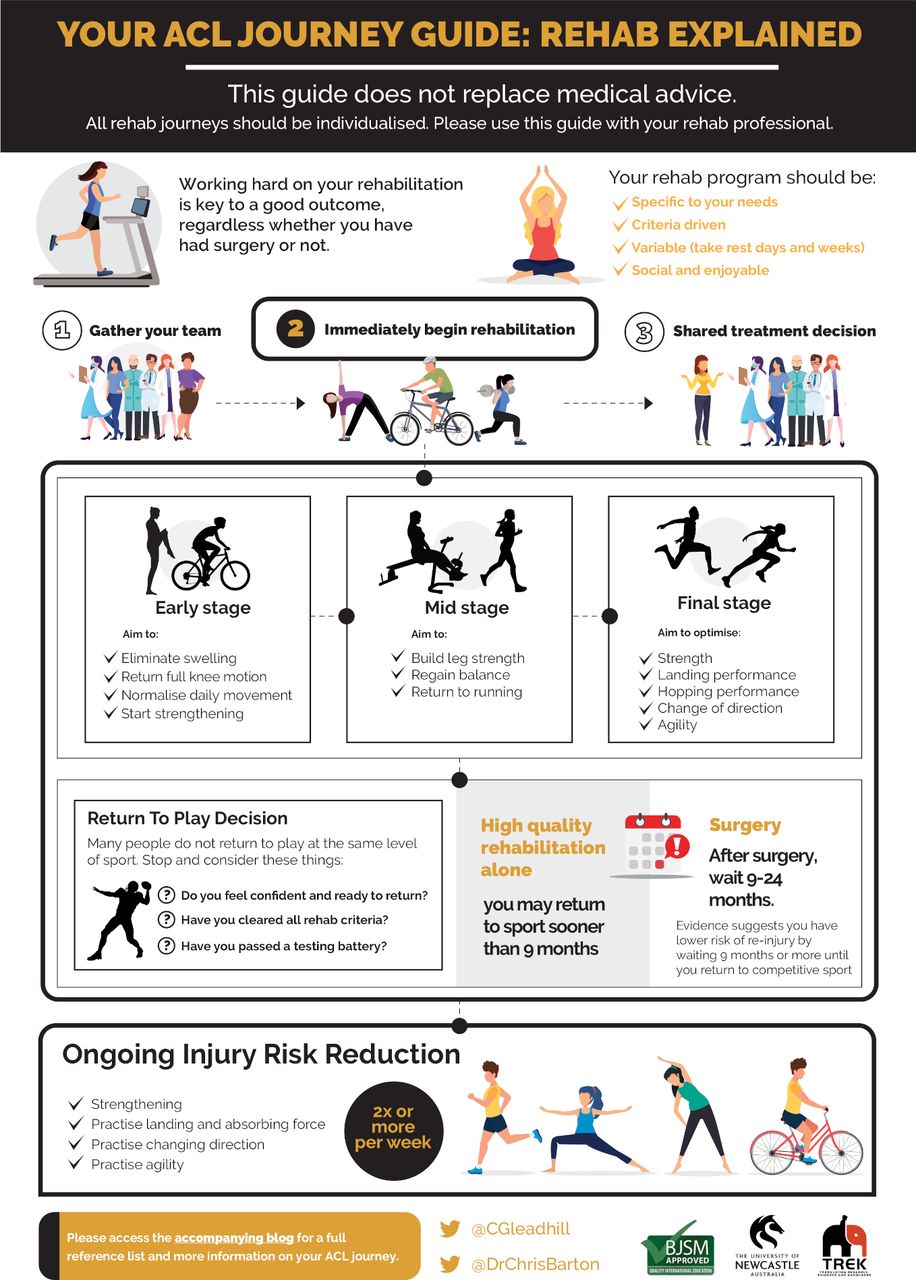

Part 2: Rehab Explained

Working hard on your rehabilitation

Whether you have surgery or not, completing quality rehabilitation is the key to restoring normal knee function, preventing further knee injury and optimising your long-term quality of life (2). You should progress through an individualised, criterion based program, involving 3 distinct ‘phases’ (early, mid and late) (12). Exercises you can think about performing in these stages are as follows (remember to perform these exercises with the guidance of a health professional):

- Early:

- Exercises to straighten and bend the knee like using your front leg muscles to straighten the knee and an exercise bike to improve your bending.

- Exercises to strengthen your front leg muscles like leg extensions.

- Practising weight bearing and walking evenly on both sides.

- Middle:

- Exercises to improve your single leg balance and control (like standing on one leg or standing on one leg on an uneven surface)

- Exercises to improve your general leg strength with squats, lunges, and deadlifts.

- Exercises to improve your single leg strength with single leg extension, single leg squats.

- Practising running.

- Late:

- Exercises to improve your landing ability (like hopping and landing practice)

- Exercises to improve your ability to change direction.

- Practising unexpected change of direction or agility (like sport-related drills with a ball, other unexpected challenges).

- Gradually returning to sport-related activities.

You need to work hard during each phase in order to optimise outcomes. People with better functional performance have lower chance of re-injury and better long term outcomes, including lower rates of osteoarthritis (13, 14, 15, 16).

When to return to play

During the final stage of rehab, people often face a difficult decision – when are you ready to return to sport? Some sobering news is that 56% of people do not return to competitive sport after an ACL injury (17). Additionally, evidence suggests up to 24% of people can re-injure their knee after returning to sport, however this risk is significantly reduced in people who pass important return to sport criteria (18). You can optimise your chances of returning to sport and reduce your risk of re-injury by considering the following:

- Work hard on your rehabilitation, and if possible, work with a qualified professional to provide you with the most up-to-date guidance.

- You should wait at least 9 months before returning to sport if you have had ACL reconstruction surgery (2). The longer your wait, the lower your chances are of re-injury. If you have not had a surgical reconstruction, the optimal timeframe to return to play is not clear, but you may be able to return to sport sooner.

- Before returning to sport, you should include sport-specific training as part of your rehabilitation, and you should pass a battery of performance tests (e.g. hop tests) (1, 12, 18).

- Ensure you are confident to return to sport before actually returning (1). Time and quality rehabilitation can help with confidence. In some circumstances, consulting with a sports psychologist might be beneficial.

How to reduce the likelihood of injury

Exercise based injury reduction programs can reduce the incidence of ACL injuries (19). These programs are important to undertake, whether you have had an ACL injury or not. Completing these programs is an important consideration as you near the final stages of your ACL journey and should be front and centre of your mind long after you return to sport. There are many injury reduction programs to choose from, including the FIFA 11+ program, the Netball KNEE Program, the Prevent injury and Enhance Performance (PEP) Program, the ACTIVATE World Rugby program, and it can be a confusing time choosing the best option for you and your sport. There are a few key components of effective programs, including regular strengthening and neuromuscular challenges like landing and agility practice (19). Remember to involve your coach and teammates when you are performing these programs – it’s everybody’s business to reduce the risk of injuries.

Authors:

Connor P Gleadhill

Christian J Barton

REFERENCES

- Ardern CL, Kvist J, Webster K. Psychological aspects of anterior cruciate ligament injuries. Operative Tech in Sports Med 2016;24:77-83. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.otsm.2015.09.006.

- Filbay SJ, Grindem H. Evidence-based recommendations for the management of anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) rupture. Best Practice & Research Clin Rheum 2019;33:33-47. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.berh.2019.01.018.

- Diermeier T, Rothrauff B, Engebretsen L et al. Treatment after Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury: Panther Symposium ACL Treatement Consensus Group. The Orthop J Sports Med published online first June 24, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F2325967120931097.

- Grindem H, Eitzen I, Engebretsen L. Nonsurgical or surgical treatment of ACL injuries: knee function, sports participation, and knee reinjury: The Delaware-Oslo Cohort Study. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2014;96(15):1233-1241. https://doi.org/10.2106/jbjs.m.01054.

- Webster K, Feller J. Exploring the high reinjury rate in younger patients undergoing Anterior Cruciate Ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med 2016;44(11):2827-2832. https://doi.org/10.1177/0363546516651845.

- Claes S, Hermie L, Verdonk R et al. Is osteoarthritis an inevitable consequence of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction? A meta-analysis. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2013;21(9):1967-1976. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-012-2251-8.

- Van Yperen D, Reijman M, van Es E et al. Twenty-year follow-up study comparing operative versus nonoperative treatment of anterior cruciate ligament ruptures in high-level athletes. Am J Sports Med 2018;46(5):1129-1136. https://doi.org/10.1177/0363546517751683.

- Diermeier T, Rothrauff B, Engebretsen L et al. Treatment after anterior cruciate ligament injury: Panther Sympsosium ACL Treatment Consensus Group. Orthop J Sports Med published online first June 24 2020;https://doi.org/10.1177%2F2325967120931097.

- Frobell RB, Roos HP, Roos EM et al. Treatment for acute anterior cruciate ligament tear: five year outcome of randomised trial. BMJ 2013;346:f232 https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.f232.

- Chalmers PN, Mall NA, Moric M et al. Does ACL reconstruction alter natural history; A systematic literature review of long-term outcomes. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2014;96A(4):292-300. https://doi.org/10.2106/jbjs.l.01713.

- Weiler R, Monte-Colombo M, Mitchell A et al. Non-operative management of a complete anterior cruciate ligament injury in an English Premier League football player with return to play in less than 8 weeks: applying common sense in the absence of evidence. BMJ Case Rep 2015 Apr 26. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2014-208012.

- Van Melick N, van Cingel REH, Broojimans F et al. Evidence-based clinical practice update: practice guidelines for anterior cruciate ligament rehabilitation based on a systematic review and multidisciplinary consensus. Br J Sports Med 2016;50:1506-15. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2015-095898.

- Pinczewski LA, Lyman J, Salmon, LJ. A 10-year comparison of anterior cruciate ligament reconstructions with hamstring tendon and patellar tendon autograft: A controlled, prospective trial. Am J Sports Med 2007;35(4):564-574. https://doi.org/10.1177/0363546506296042.

- Grindem H, Risberg MA, Eitzen I. Two factors that may underpin outstanding outcomes after ACL rehabilitation. Br J Sports Med Published Online First: 14 July 2015. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2015-095194.

- Toole AR, Ithurburn MP, Rauh MJ et al. Young athletes cleared for sports participation after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: How many actually meet recommended return-to-sport criterion cutoffs? J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2017;47(11):825-833. https://doi.org/10.2519/jospt.2017.7227.

- Patterson B, Culvenor A, Barton C et al. Poor functional performance 1 year after ACL reconstruction increases the risk of early osteoarthritis progression. Br J Sports Med 2020;54:546-553. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2019-101503.

- Ardern CA, Webster KE, Taylor NF et al. Return to sport following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the state of play. Br J Sports Med 2011; 45: 596-606. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bjsm.2010.076364.

- Grindem H, Snyder-Mackler L, Moksnes H et al. Simple decision rules can reduce reinjury risk by 84% after ACL reconstruction: the Delaware-Oslo ACL cohort study. Br J Sports Med 2016;50:804-808. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2016-096031.

- Arundale AJH, Bizzini M, Giordano A et al. Exercise-based knee and anterior cruciate ligament injury prevention clinical practice guidelines linked to the international classification of functioning, disability and health from the Academy of Orthopaedic Physical Therapy and the American Academy of Sports Physical Therapy. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2018;48:A1-A42. https://doi.org/10.2519/jospt.2018.0303.

-