Follow-up to BJSM podcast episode #322. Haven’t heard it yet? Listen here.

By Erin Macri @Erin_Macri, Simon Kristoffer Johansen, Michael Rathleff @MichaelRathleff

After interviewing Dr. Michael Rathleff, I was thinking about how best to introduce Michael’s education slides to the clinic. Rather than simply uploading them to the site, I have collaborated here with Michael and his PhD student, Simon (who is doing qualitative research on adolescent knee pain), to walk us through the education slides and offer evidence-informed insights on how to optimize our education efforts for adolescents with patellofemoral pain.

Pointers for including the slides as a tool for supporting behaviour change in a clinic setting.

If only showing a few educational slides were enough to facilitate behaviour change in a clinical setting! Dr. Rathleff acknowledges that knowing WHAT to educate on is only the first step. As a clinician, I need to know HOW to meaningfully use the slides in a way that makes sense to the adolescent and their parents/coaches, but also empowers and motivates the adolescent. Also, WHEN should I use the slides and WHO will benefit most from these slides?

One model of behaviour change, The Fogg Behavior Model identifies three critical components to elicit a new behaviour: (i) motivation, (ii) ability, and (iii) a triggering event. Your patient may be more inclined to undertake a hard task (one that requires high ability) if their motivation is equally high when triggered (by your educational slides and their life situation). On the other hand, in a patient with low motivation, how we choose to share our knowledge about patellofemoral pain with the patient could make or break whether or not the adolescent will make choices towards better self-management.

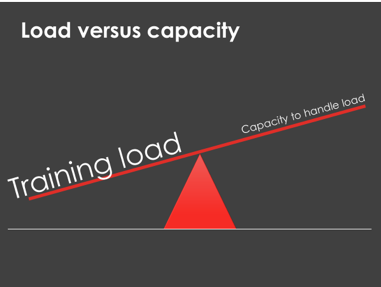

Slide 1. The See Saw

FRONT SLIDE: Show the patient that if they keep fully participating in their sports (with the same training errors) during a patellofemoral pain episode, the capacity to handle that training load may be compromised.

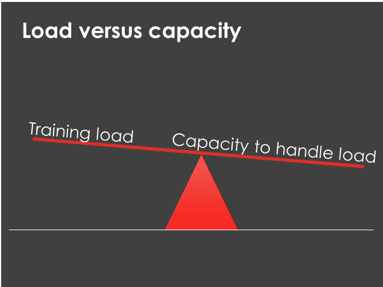

BACK SLIDE: Their goal during the painful episode, as well as in the future, should be to balance (and self-manage) their training loads with current capacity to handle these loads. Capacity can encompass both tissue capacity of the knee, but also all relevant physiological features (e.g. kinetic chain strength) and psychological features (e.g. depression) that can influence their condition and symptoms.

Slide 2. The See Saw in Action

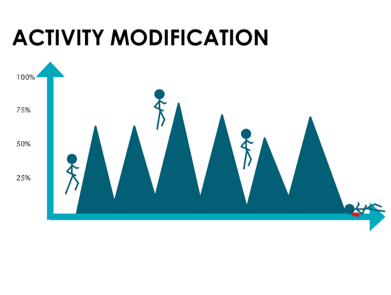

FRONT SLIDE: Our athlete enthusiastically jumps into their sports or activities with abandon, not considering their current tissue capacity or fitness level. With each ‘mountain’ they climb (an analogy for a bout of training, whether acute or chronic overload), the See Saw (above slide) tips in response to the heavy training load. They feel pain, but either tough it out until the sport ends, or they simply stop. Either way, they follow their overtraining with rest and never gradually build capacity before experiencing a new episode of pain. As soon as the pain decreases, they jump back into their activities full bore. The cycle repeats.

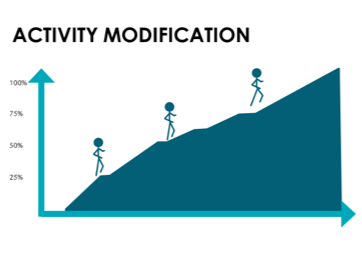

BACK SLIDE: Our athlete considers their knee and what they need to get stronger and more able to withstand load. They modify their activities accordingly, playing sports and treating their knee in a way that slowly builds their load capacity as well as their abilities to manage pain when it emerges. They balance the See Saw. By the end of treatment, their capacity is far greater than it ever was when they were on the See Saw!

MOTIVATION: By illustrating the relationship between training load and capacity for handling load in a way that is relatable to adolescents, slides 1 & 2 connect the target behaviour (load management to balance the See Saw) to the adolescents’ pain experience. Their knee pain becomes a trigger for behavioural change. The education gives them actionable information: they now have choice, and slide 3 gives them a path of action.

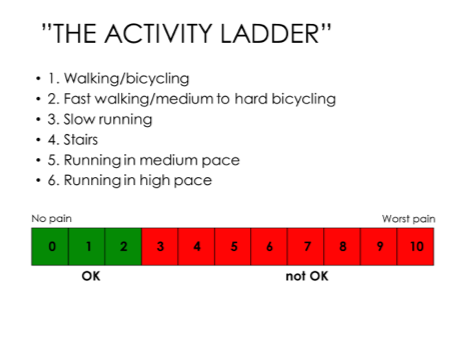

Slide 3. The Activity Ladder

Rest does not cure patellofemoral pain! It is critical for the adolescent to stay active, but to learn to self-manage their activities and modify loads accordingly. Moreover, it is ok – even important – to work into some pain when managing patellofemoral pain. The slide below offers a visual guideline for knowing when it is ok to keep moving, and when to modify activities. It also offers a progressive list of types of activities to help guide activity modifications: for example, if slow running is tolerated with no more than 2/10 pain, then it is ok to start doing stairs for activities and after step 6, they are encouraged to go back to sport. The activity ladder is designed to give adolescents (and parents) a simple framework on how to progress activities and when to return back to sport.

MOTIVATION: This slide aims to RAISE motivation to adhere to their treatment by harnessing the adolescent’s hopes and desires (e.g. participating in sports requires running). It also gives a concrete breakdown of tasks to help them set achievable sub-goals. By using the ladder and pain-scale, the adolescent’s focus gradually shifts from pain avoidance towards pain-management and functional goals.

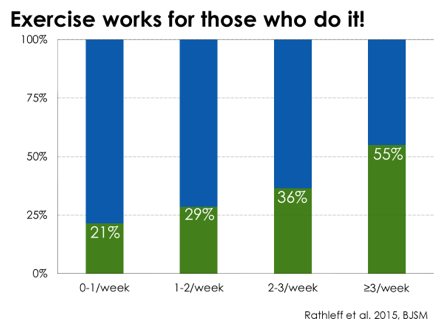

Slide 4. Diligence is key

The below graphic shows the % of participants who recovered from patellofemoral pain with an exercise-based intervention. Importantly, those who did their therapeutic exercises at least 3 days per week were more likely to improve compared to those less adherent to the exercises. The take home message: recovery hinges upon your own commitment to self-management.

MOTIVATION: This slide visualizes the importance of adherence, reaffirms the credibility of the treatment plan by highlighting the success of others. This makes the adolescent aware of their personal role in rehabilitation.

Pointers:

The role of the clinician is: (i) to design treatments that enhance the adolescents’ ability to maintain performance and acquire skills, (ii) to help motivate the adolescent by understanding their individual needs, and (iii) provide feedback and correct misconceptions to optimize their self-management.

Through the research conducted at the Research Unit for General Practice in Aalborg, we present a few tips for clinicians to optimize the use of these slides. We encourage you to be reflective in your approach to see what works best for your patients!

Get to know the patient and their supporters: Adolescents are not small adults and clinicians must remember this when educating adolescents. Despite the fact that knee pain often manifests in similar ways, the adolescents experiencing the pain have unique needs and expectations in terms of treatment and recovery. While the tool relies on motivation for behavioural change, understanding what my adolescent patient is passionate about and willing to work for (e.g. returning to soccer practice) and their pitfalls (e.g. too much activity at once) is critical for establishing shared goals and building a strong clinician-patient relationship with both the adolescent and their parents. Engaging the parents from the beginning is vital –their support is critical when the adolescent is trying to integrate what they have learned into their daily lives.

Plan on multiple sessions: Learning how to manage knee pain is like learning a new language. While you consult professionals for vocabulary and pronunciation, the bulk of learning happens when you regularly practice speaking the language. As with language, managing knee pain requires in-field experimentation before it becomes fully understood and integrated into everyday life. It is impossible to learn the entire language of self-management in one session. It will require experimentation by the adolescent with clinician feedback to understand their symptoms and gain control of their pain.

Ask, listen and correct false beliefs: Ongoing qualitative interviews with adolescents and young adults tells us that adolescents, prior to consulting with a clinician, will form theories on why their pain emerges and how to best deal with it. They may believe that ‘pain is part of adult life’, ‘I have to lose weight’, or ‘it only hurts when I climb stairs’. Since some beliefs can negatively influence treatment and reinforce worries and fear, asking adolescents why they believe they get pain may inform the clinician’s role in educating their patient.

Build a vocabulary for self-management: Words are powerful. They can reveal how we perceive our world. Listen to how your patient uses words when describing their pain (e.g. ‘hitting the wall’, ‘there was nothing I could do’). Try to find metaphors that align with the specific behaviour you want to influence (e.g. balancing the See Saw, finding the limit, saving up points) – this can powerfully support the adolescent in remembering to use the slides between consultations.

Be present, fair and constructive: Adolescents generally perceive feedback from clinicians as credible and important for guiding their self-management decisions. Still, they may doubt whether their knee pain merits seeing a clinician. As a clinician, avoid behaviors like downplaying the adolescent’s experience or criticizing them for making wrong decisions – this may reinforce the belief that they should not seek treatment. Be mindful and constructive. Use active listening strategies, recognize their efforts, and make their performance the object of your feedback.

Encourage them to search out tools on their own: Mobile self-tracking apps, step-counters, and other self-management tools require meta-reflection and can both motivate and empower your patient. As the adolescent gains control over their condition, they will discover and reflect on new ways to manage their pain. As a clinician, stay open minded to what the adolescent brings to their treatment. Encourage their engagement and desire to take ownership of their goals and treatment process. Just make sure that the tools included do not introduce new misconceptions, and that they carry over from the clinical setting into the adolescents´ everyday life.

Erin Macri is a physical therapist and postdoctoral researcher at the University of Delaware with a special interest in patellofemoral pain and osteoarthritis.![]() @Erin_Macri

@Erin_Macri

Simon Kristoffer Johansen is a Master of Arts in Human-Centered Informatics and PhD student at the University of Alborg in Denmark. His interest lies in Health Informatics, Patient education, Learning theory and Participatory design. He is currently studying use of pain stories to explore learning in adolescents with knee pain via semi-structured interviews.

Michael Skovdal Rathleff is an associate professor and head of the OptiYouth research group that works towards improving musculoskeletal health in adolescents. ![]() @MichaelRathleff

@MichaelRathleff