Last week I discussed how the Medicines Act 1968 enabled the promulgation of the Human Medicines Regulations 2012, which replaced the Act and about 200 other pieces of secondary legislation.

Last week I discussed how the Medicines Act 1968 enabled the promulgation of the Human Medicines Regulations 2012, which replaced the Act and about 200 other pieces of secondary legislation.

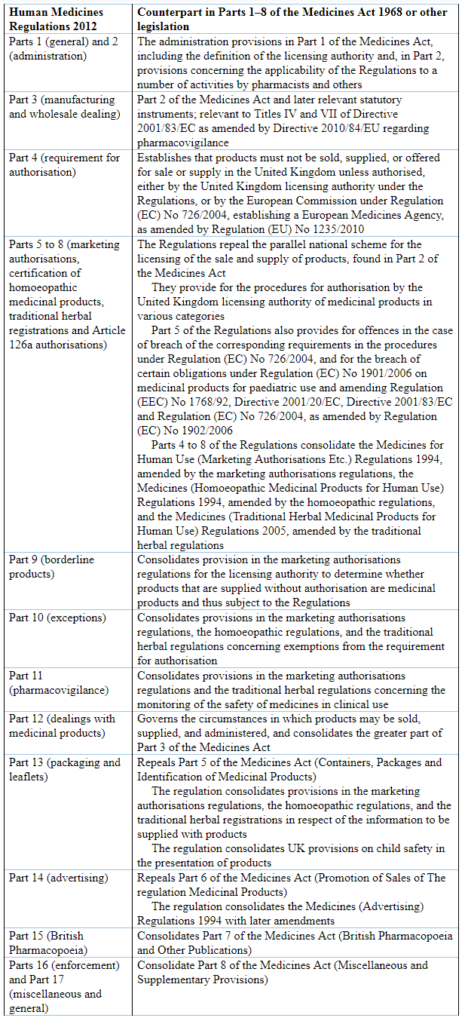

The Medicines Act contained 136 sections in eight parts plus eight appended schedules. In contrast, the Human Medicines Regulations contains 349 sections in 17 parts plus 35 appended schedules. The general correspondences between the two are shown in Table 1 below. I do not intend to make a detailed direct comparison between the two. I have previously discussed the licensing of medicines and how they are advertised and described in the light of the Medicines Act 1968. Here I shall describe how the major parts of the 2012 Regulations deal with advertising, to exemplify the similarities and differences.

Table 1. A brief comparison of the contents of the Human Medicines Regulations 2012 and the Medicines Act 1968; for complete details see the Explanatory Note at the end of the former

The Medicines Act 1968 (§92–97) made it illegal to give false or misleading information and to advertise unauthorized (i.e. “off-label”) recommendations. The Act also empowered the licensing authority to require copies of any advertisements and data sheets relating to medicinal products to be provided, and to ensure that they contained adequate information, did not include misleading information, and promoted safety.

These provisions are retained in the 2012 Regulations (§282–303) but the Regulations are more extensive and include additional provisions, such as those relating to advertisements wholly or mainly directed at members of the public (§283–292), proscribing, for example:

- advertisements likely to lead to the use of a medicinal product for the purpose of inducing an abortion;

- advertisements for prescription only medicines and for substances listed in Schedules I, II, or IV to the Narcotic Drugs Convention or in Schedules I to IV to the Psychotropic Substances Convention;

- advertisements that state or imply that a medical consultation or surgical operation is unnecessary, that offer to provide a diagnosis or suggest a treatment by post or by means of an electronic communications network, or that might, by a description or detailed representation of a case history, lead to erroneous self-diagnosis;

- advertisements that suggest that the effects of taking the medicinal product are guaranteed, are better than or equivalent to those of another identified treatment or product, or are not accompanied by any adverse reaction;

- advertisements that use misleading or alarming pictorial representations of changes in the human body caused by disease or injury or that misleadingly or alarmingly refer to claims of recovery;

- advertisements that suggest that health in the absence of disease or injury could be enhanced by taking the product or affected by not taking it;

- advertisements directed principally at children

These Regulations do not apply to advertisements for approved vaccines or sera in vaccination campaigns.

The Regulations proscribe abbreviated advertisements, which in essence means that they must contain information about adverse reactions, precautions, contraindications, and method of use, or at least a statement that the information can be found at a given website address.

Other provisions relate to:

- promotion of medicinal products by medical sales representatives;

- free samples for persons qualified to prescribe or supply medicinal products;

- inducements and hospitality, although without defining the meaning of “inexpensive”;

- advertisements for registered homoeopathic medicinal products;

- advertisements for traditional herbal medicinal products.

I have previously suggested that the provisions in the Medicines Act 1968 may have contributed to the decline in advertising of medicinal products that occurred during the 1970s and 1980s. It is too soon to say what effect the 2012 Regulations will have.

Jeffrey Aronson is a clinical pharmacologist, working in the Centre for Evidence Based Medicine in Oxford’s Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences. He is also president emeritus of the British Pharmacological Society.

Competing interests: None declared.