As I discussed last week, Clinical Pharmacology Month, currently in progress, is a good occasion during which to reflect on the 50th anniversary of the Medicines Act 1968 and its ramifications. Part II of the Act (§§6–50) dealt with licensing.

As I discussed last week, Clinical Pharmacology Month, currently in progress, is a good occasion during which to reflect on the 50th anniversary of the Medicines Act 1968 and its ramifications. Part II of the Act (§§6–50) dealt with licensing.

The IndoEuropean root LĒ, to let go or slacken, gives us let (Old English lǽtan), liege and allegiance (Old High German ledig, free), lenient and lenity (Latin lenis, soft or gentle), and lassitude and alas (Latin lassus, weary). “Licence” derives from the Latin word licentia, the freedom to act as one pleases, lack of restraint, permission, or opportunity. Licence originally, when it entered English in the 14th century, meant leave, permission, or liberty to do something, typically to depart. By the 15th century this non-count noun had also become a count noun, a licence, “a formal, usually a printed or written permission from a constituted authority to do something, e.g. to marry, to print or publish a book, to preach, to carry on some trade, etc” (Oxford English Dictionary), or “the document embodying such a permission”. The permission that a licence grants under the Medicines Act, a so-called product licence, now called a Marketing Authorization, is permission to the manufacturer to market a compound as a medicinal product.

Marketing Authorizations are granted to the manufacturer, who is licensed, not the product. Nevertheless, shorthand terms such as “licensed drug”, “licensed medicine”, and “licensed product”, which are not strictly accurate, are commonly used colloquially. Thus, in the UK, a licensed product is one whose manufacturer has been granted a licence to market it for specified indications and in specified ways, the description of which is called the label; an unlicensed product is one for which no licence has been issued for any indication.

The IndoEuropean root AUG, to increase, gives us the Old English word eke and hence an ekename or a nickname. Auxesis, plant growth, and auxins, plant growth hormones, are from the Greek word αὔξειν, to increase; auxesis is also a rhetorical figure like hyperbole. Other derivatives, related to the Latin word augēre, to increase, include auction, augment, augur and inaugurate, august, and auxiliary. Auctor, also from augēre, was someone with authority (auctoritas) to take action or make a decision; an actor was originally someone who instigated or was involved in a legal action. And someone with authority could give authorization.

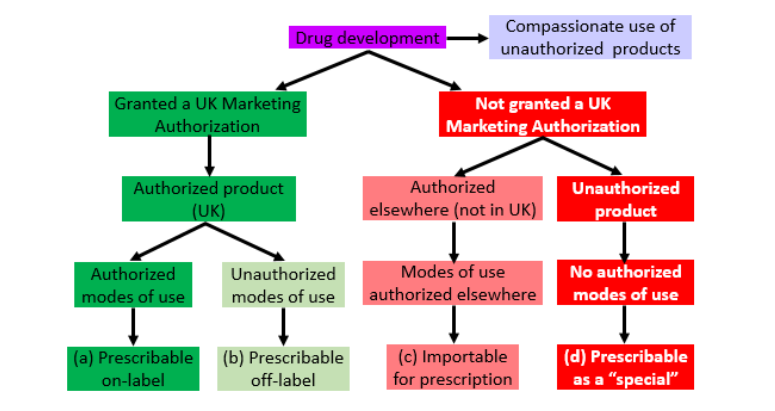

Since product licences are now called Marketing Authorizations, the different types of licensing are better thought of as different types of authorization. These different types are shown in Figure 1. The main varieties are shown in the bottom line.

Figure 1. Different types of marketing authorization awarded to manufacturers of medicinal products (adapted from Aronson & Ferner, Br J Clin Pharmacol 2017; 83: 2615–25)

Authorized products can be prescribed either on-label (i.e. in complete accordance with the terms of the authorization; dark green) or off-label (i.e. differing in some way from the terms of the authorization; light green). For example, ranibizumab (Lucentis®), an anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (“anti-VEGF”) agent, is authorized for the treatment of age-related macular degeneration and is used for that purpose on-label. Bevacizumab (Avastin®), on the other hand is licensed to treat a range of cancers (including those affecting the colon or rectum and, in combination with other drugs, breast cancer, non-small cell lung cancers, renal cell cancer, epithelial ovarian, fallopian tube, or primary peritoneal cancers, and carcinoma of the uterine cervix), but not age-related macular degeneration; however, bevacizumab, as effective and safe as ranibizumab, is used off-label.

Recently, in the Queen’s Bench Division of the High Court of Justice, Mrs Justice Whipple dismissed a claim made by the pharmaceutical companies Bayer plc and Novartis Pharmaceuticals UK Limited against a consortium of 12 clinical commissioning groups (CCGs) who are using bevacizumab as the preferred treatment option for age-related macular degeneration, rather than the much more expensive agents ranibizumab and aflibercept. The companies challenged the lawfulness of this. The judge ruled that the use of bevacizumab was not unlawful. An important part of her judgement related to the fact that when bevacizumab is used for ophthalmic treatment, it is usually diluted (or “compounded”), a process that the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) had declared converted its use from licensed off-label to unlicensed (Figure 1, red boxes). The judge invited the MHRA to review this guidance, in other words to authorize off-label use of the compounded formulation. The financial savings to the NHS as result of this judgement should be large.

Jeffrey Aronson is a clinical pharmacologist, working in the Centre for Evidence Based Medicine in Oxford’s Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences. He is also president emeritus of the British Pharmacological Society.

Competing interests: None declared.