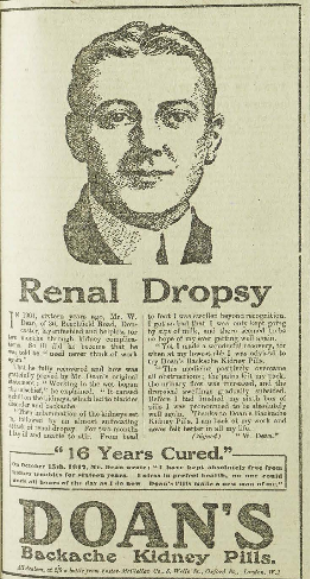

During the years spanning the 100th anniversary of the 1914–18 war, The Daily Telegraph has, day by day, been publishing facsimiles of issues of the paper that appeared 100 years ago. This advert appeared in the issue of Friday 7 December 1917.

Doan’s Backache Kidney Pills came in boxes of 40 kidney pills and 4 “dinner” pills. They would “Cure Backache, Weak Back, Rheumatism, Diabetes, Congestion of the Kidneys, Inflammation of the bladder, Gravel, Bright’s Disease, Scalding Urine, and all Urinary troubles.” Before you started taking the kidney pills, you took the dinner pills, which were also available separately for a range of other conditions, such as “Constipation, Sick Headache, Biliousness, Dizziness”. Customers were advised to keep taking them for weeks (“30 [boxes may be] required”), because resolution could be slow, and they should not feel discouraged. Indeed, feeling discouraged was asserted to be one of the symptoms of the disease!

The dinner pills contained, as far as the authors of Secret Remedies (BMA, 1909) could discover, oil of peppermint, podophyllin, aloin, jalap resin, powdered capsicum, powdered liquorice, maize starch, acacia gum, and extract of henbane. The materials for 50 pills cost one old penny—price, one and three ha’pence (about 6p).

The kidney pills contained oil of juniper, podophyllin, hemlock pitch, potassium nitrate, powdered fenugreek, wheat flour, and maize starch. The materials for 40 pills cost a ha’penny—price, two and ninepence.

Overcharging for pharmaceutical products has been with us for a long time.

“Dropsy” is an abbreviated form of hydropsy, Greek ὕδρωψ, from ὕδωρ, water, from which we get words such as hydrocele and dehydration. Elision with the definite article, by which “the hydropsy” became “th’ idropsy”, was followed by metanalysis, giving “the dropsy”.

In addition to the extensive dropsy called anasarca (ἀνά up + σάρξ flesh), Hippocrates described ὕδρωψ ξηρός, dry dropsy (gaseous distension of the belly), of two types: ὕδρωψ ὑποσαρκίδιος, hyposarca, and ὕδρωψ μετ’ ἐμϕυσημάτων, emphysematous dropsy. Galen referred to τυμπανίας ὕδρωψ, tympanitic or tight drum-like distension of the belly, due to either ascites or tympanites (distension by gas rather than liquid, also called meteorism, from the Greek μετεωρισμός lifting up, swelling), for which Pliny recommended hellebore (which contains cardiac glycosides). And Galen called diabetes ὕδρωψ εἰς ἀμίδα (pisspot dropsy).

The term later came to be used for many different forms of fluid accumulation: dropsy of the legs (peripheral oedema); hydrops abdominis (ascites); hydrops pectoris (pleural effusion); hydrops pericardii (pericardial effusion); meningeal hydrops (hydrocephalus); hydrops amnii (hydramnios); ovarium dropsy (ovarian cyst); and renal dropsy (nephrotic syndrome). Various sources, including Volume 1 of Frank Shaw’s “Lern Yerself Scouse” (Scouse Press, 1966), list “dropsy” as slang for a tip or a bribe (“Give der doorman is dropsy”), a diminutive of “drop”.

When I searched for dropsy and hydrops as textwords in PubMed I got over 7400 hits. About 40% were to do with hydrops fetalis. Endolymphatic hydrops, hydrops labyrinthi, and cochlear hydrops, other names for Menière’s disease, accounted for about 20%. Corneal hydrops (presumably not to be confused with eye drops) accounted for 2% and gallbladder hydrops for 0.7%. Hydrops was sometimes used to refer to a joint effusion and there were a few cases of hydrops tubae profluens (intermittent hydrosalpinx or hydrorrhoea tubae intermittens), when a blocked Fallopian tube swells, bursts, and drains into the vagina, giving what looks like urinary incontinence, which can occur through carcinoma of a Fallopian tube or after hysterectomy.

Epidemic dropsy, which is seen mostly in India, but has also been reported in Mauritius, Fiji, South Africa, and Nepal, accounted for 2.4% of my hits. It is due to ingestion of mustard oil or ghee adulterated with oil from the seeds of Argemone mexicana (the Mexican poppy), which contain a toxin called sanguinarine, so called because it was first identified in Sanguinaria canadensis, the blood-root. Epidemic dropsy presents with gastrointestinal symptoms a week or so before the onset of pitting oedema of the legs, fever, and darkening of the skin, often with local erythema and tenderness. Perianal itching is common, and myocarditis and congestive cardiac failure can occur. Other features include anaemia, hepatomegaly, pneumonia, ascites, glaucoma, alopecia, and sarcoid-like skin changes.

Eight papers from my search dealt with renal dropsy. The earliest, from 1871, reported on a case of syphilitic renal dropsy, with epithelial and granular casts and albuminuria. In passing, the author criticized Aristotelian logic, in the form that was invented long after Aristotle—drawing deductions from unproven hypotheses. He recommended mercury in treatment, effective for the syphilis perhaps, but itself a possible cause of the nephrotic syndrome.

In 1918, contemporaneous with the advert for Doan’s pills, Sir Clifford Allbutt, published an account of a case of renal dropsy in The BMJ: “body and legs enormously swollen—face, back, loins, legs, and private parts—and pitting deeply on pressure everywhere…huge anasarca.” He treated it successfully with a low fat, high protein diet.

Of words beginning with hydro- listed in the Oxford English Dictionary hydrotic is the odd one out, being a misspelling for hidrotic, which comes from another Greek word, ἱδρώς, meaning sweat. The Greek word ὕδρωψ came from the Indo-European root AUE, which also eventually gave rise to such diverse words as hydra, urology, undulate, and water itself. On the other hand, ἱδρώς came from the root SUEID, which gave sudorific, exude, sauna, and of course sweat. But this is an understandable error—confusing sweat with water.

Jeffrey Aronson is a clinical pharmacologist, working in the Centre for Evidence Based Medicine in Oxford’s Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences. He is also president emeritus of the British Pharmacological Society.

Jeffrey Aronson is a clinical pharmacologist, working in the Centre for Evidence Based Medicine in Oxford’s Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences. He is also president emeritus of the British Pharmacological Society.

Competing interests: None declared.