Magazines have a long and distinguished history.

Magazines have a long and distinguished history.

The Oxford English Dictionary defines a magazine as “a periodical publication containing articles by various writers; esp. one with stories, articles on general subjects, etc., and illustrated with pictures, or a similar publication prepared for a special interest readership.” A periodical is “a magazine or journal issued at regular or stated intervals (usually weekly, monthly, or quarterly).” To each of these definitions the dictionary adds a note to the effect that “periodical” is now usually reserved for academic journals and “magazine” for more popular publications. “Magazine” dates from about the 1730s, “periodical” from the 1780s.

The earliest literary periodical published in England was Mercurius Librarius, a booksellers’ trade journal, founded in 1668 by two stationers, John Starkey and Robert Clavell. It lasted until 1709, the year in which The Tatler was first published by Richard Steele, using the pseudonym Isaac Bickerstaff. Steele and Joseph Addison replaced The Tatler in 1711 with The Spectator, which continued off and on until 1714. Several other later publications also took the name Tatler; the modern version was first published in 1901 by Clement Shorter. The modern Spectator was founded in 1828 by Robert Stephen Rintoul.

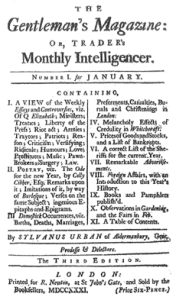

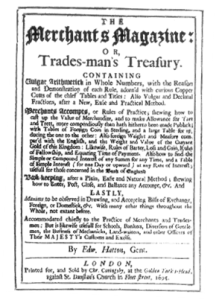

The Gentleman’s Journal, edited by Pierre Antoine Motteux, translator of Rabelais and Don Quixote, first appeared in 1692 and contained news, poetry, and prose; however, it lasted only until 1694. Edward Cave revived it in January 1731, as The Gentleman’s Magazine (picture), the first periodical to use the term “magazine”, although the term had already been used in the titles of books, such as The Merchant’s Magazine: or, Trades Man’s Treasury (1695) by Edward Hatton (picture). Other magazines followed at intervals: The London Magazine in 1732, The Royal Female Magazine in 1760, The Town and Country Magazine in 1769, The New Monthly Magazine in 1814 (founded in political opposition to The Monthly Magazine), and Blackwood’s Magazine in 1817 (founded as a rival of The Edinburgh Review). Some titles did not bear the word “magazine”, but they were magazines nevertheless: Fielding’s The Champion (1739), Johnson’s The Rambler (1750), Smollett’s Critical Review (1756), Coleridge’s The Watchman (1796), Bentley’s Miscellany (1837).

Images: Left: The title page of the first issue of The Gentleman’s Magazine, January 1731; the Latin tag “prodesse et delectare” (“to serve and entertain”) was borrowed from The Gentleman’s Journal and is a paraphrase of a line in Horace’s Ars Poetica, “Aut prodesse volunt aut delectare poetae” (“poets want either to serve or entertain”)

Right: The title page of The Merchant’s Magazine (1695)

Magazine is from a Semitic root, ḫsn, strong, giving the Aramaic word ḥassen, to own, since ownership is empowering. Makhsan in Hebrew (מחסן) and Arabic is a storehouse or depot. It gave magazzino in Italian, magasin in French, and, prefixed with the Arabic definite article, almacén in Spanish and armazém in Portuguese. It entered English in the late 16th century, when it meant a general storehouse for goods or merchandise, a warehouse or depot. This meaning was later extended to storehouses for munitions and other military provisions, and figuratively as a store of ideas. Magazine programmes, mixtures of items, first appeared in the 1920s. In French “magasin” is a faux ami—it does not mean a magazine but a shop, retaining the earlier implication of a storehouse; a magazine is périodique or magazine.

In 2002 Richard Smith described how The BMJ was changing from a journal, like Brain, into a magazine, like Cosmopolitan. The sobriquet “British Medical Magazine” that some of us then used was not, I think, particularly well regarded in BMA House. Now, however, it has been fully espoused. In her “Editor’s Choice” column in the print issue dated 24 October, the editor described the changes that have been made to the print issue. “We heard,” she wrote, “that you want something in print that is easier to digest, something you can dip into quickly, . . . fewer words, more pictures. . . The result is this redesigned weekly magazine.” She used similar words in her speech at Wednesday’s BMJ Xmas party (officially known as the “Friends of the Journal drinks reception”). The OED definition quoted above is pertinent.

This has also come about, if I interpret correctly, partly because of the success of BMJ Open as an online academic wing of The BMJ and the decision to issue a monthly academic print version. The new print version of The BMJ is an excellent magazine, greatly welcome.

PS: Thanks to Liz Wager for asking the question.

Jeffrey Aronson is a clinical pharmacologist, working in the Centre for Evidence Based Medicine in Oxford’s Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences. He is also president emeritus of the British Pharmacological Society.

Competing interests: None declared.