Keywords: disability, sport, cerebral palsy

In this blog we explain how we used a novel single-case experimental research design to investigate the therapeutic value of participation in Para sport. Our study enrolled young people with profound cerebral palsy and high support needs in a Para swimming training program called ParaSTART and monitored their training load, sports performance and gross motor function over 4 years [1].

You can watch a brief video on the ParaSTART program here.

Why is this study important?

Young people with profound cerebral palsy and high support needs (CPHSN) are highly inactive and experience meaningful decline in their gross motor function during adolescence [2] [3]. This means that this group gradually has less independence, more challenges in doing activities of daily living and their mobility becomes poorer. Unfortunately, this decline is accepted as inevitable in clinical practice and results in poor health outcomes. It is possible that the relative inactivity of young people with CPHSN contributes to the decline and our study was the first to investigate this premise.

This study was important because the population of focus was a unique, understudied group – young people with CPHSN face great barriers to participation in sport and require significant support to reduce the risk of adverse events. The use of sport as the intervention was also important. The aim of the training intervention was solely to improve sports performance – to help participants be as good as they could be in Para swimming – as opposed to recreational or therapeutic exercise. Lastly, we used a novel research design which allowed us to tailor the training program to meet the unique needs of participants, and longitudinally monitor their gross motor function during a life-stage when decline is expected.

How did the study go about this?

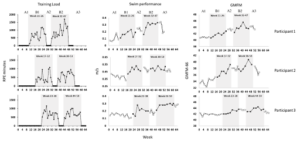

We recruited 3 young people with CPHSN into a multiple-baseline, single-case experimental design (MB-SCED) study comprising five phases (A1-B1-A2-B2-A3) with a 30-month follow-up. ‘A’ phases were baseline or rest periods, and ‘B’ phases were swimming training intervention periods. The training delivery team was multidisciplinary and comprised coaches, physiotherapists, exercise physiologists, medical doctors and psychologists – each were critical in safely and effectively implementing the training program. We conducted repeated measures of motor function throughout the duration of the MB-SCED study (total timepoints = 102). Following this, we monitored participants for a further 3 training seasons over the next 3 years [1].

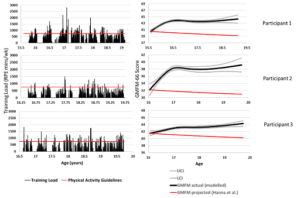

To find out whether their swimming training influenced function, we compared the trajectory of each participants’ gross motor scores against their own baseline, and against the decline predicted by population-based modelling [3].

Methodologically, the MB-SCED offered to us a robust alternative to a Randomised Controlled Trial (RCT) – implementing a safe, effective training program for a sample of sufficient size and homogeneity for an RCT was infeasible in this case. The MB-SCED generated high-level evidence from a small sample and offered many advantages including: permitting the allocation of time and expertise to safely supervise participants in the pool; providing personalised assistance; and permitting us the freedom to individualise training programs without compromising experimental control [4].

What did the study find?

Overall, participants were highly engaged with the program and accumulated training volumes similar to World Health Organisation physical activity recommendations. Engagement was sustained – the participants still train with the ParaSTART program today (7 years later). The improvements we observed in motor function scores in response to training were significant in all participants, and two periods of training withdrawal each resulted in significant motor decline. Participant motor function remained above baseline levels for the study duration, and, importantly, participants did not experience the motor decline typical of other adolescents with CPHSN.

Figure 1: Training Load, swimming performance and GMFM-66 data for each participant throughout the 5-Phase A1-B1-A2-B2-A3 SCED study.

Figure 2: Longitudinal training load and GMFM-66 data. The left panel displays training load data for each participant between the age of 15/16 years and 19/20 years (displayed x-axis; note that the baseline period is not temporally represented). The red horizontal line denotes the RPE-minute value commensurate with national physical activity guidelines (750 RPE mins/wk). The right panel displays modelled GMFM data for each participant, with 95% confidence intervals, and the red line denotes the projected trajectory of motor decline, from the median of baseline GMFM-66 scores.

What are the key take-home points?

Competitive sport provides an age-appropriate, self-directed, sustainable context for young people with profound CP to achieve physical activity guidelines and maintain their gross motor function. These findings are not just relevant for Paralympic athletes. At the commencement of the trial participants in this study were not athletes – in fact they had no swimming training experience at all. Training volume (intensity x frequency x duration) and prolonged engagement appear to be critical. However, this population is clinically complex, and in order to permit safe, effective participation in competitive sport, priority should be placed on the development of programs delivered by skilled multi-professional teams.

Authors: Iain Dutia, Emma Beckman and Sean Tweedy

References:

- Dutia, I.M., et al., The power of Para sport: the effect of performance-focused swimming training on motor function in adolescents with cerebral palsy and high support needs (GMFCS IV) – a single-case experimental design with 30-month follow-up. Br J Sports Med, 2024. 58(14): p. 777-784.

- Verschuren, O., et al., Exercise and physical activity recommendations for people with cerebral palsy. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 2016. 58(8): p. 798-808.

- Hanna, S.E., et al., Stability and decline in gross motor function among children and youth with cerebral palsy aged 2 to 21 years. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 2009. 51(4): p. 295-302.

- Nikles, J. and G. Mitchell, The Essential Guide to N-of-1 Trials in Health. 1st ed. 2015.. ed, ed. P. SpringerLink Content. 2015, Dordrecht: Dordrecht : Springer Netherlands : Imprint: Springer.