Diagnosing, managing & rehabilitating injuries in the Bermuda Triangle

Keywords: Groin Pain; Pubic Pain; Pubalgia; Rehabilitation

Introduction

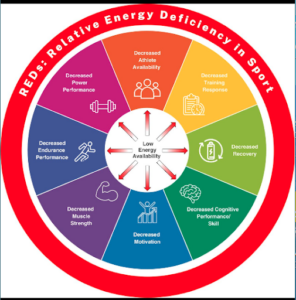

This final blog in the series covers Pubic Related Groin Pain (PRGP) (1). Earlier parts to the series can be found by following: Part 1 Adductor Related Groin Pain (ARGP); Part 2 Iliopsoas Related Groin Pain (IRGP) and Part 3 Inguinal Related Groin Pain (IgRGP). In keeping with most other musculoskeletal (MSK) sporting injuries, history of previous groin injury puts the athlete at greater risk of further episodes (2). For athletes involved in team sports exposed to acceleration, deceleration or dynamic directional changes, overload can result in in PRGP (2), (3), (4), (5), (6), (7), (8), (9), (10), (11), (12), (13), (14), (15), (16), (17) & (18). In endurance, artistic or aesthetic sports PRGP may occur due to Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (REDs) (Figures 1 and 2) (19).

Figure 1 Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (REDs) Health Conceptual Model (Mountjoy M, Ackerman K, Bailey DM, et al. 2023) (19)

Figure 2 Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (REDs) Performance Conceptual Model (Mountjoy M, Ackerman K, Bailey DM, et al. 2023) (19)

Pubic Related Groin Pain (PRGP)

PRGP is defined as local tenderness of the pubic symphysis and the immediately adjacent bone (1). No particular resistance tests specifically test for PRGP, although the “squeeze test” would appear to be most relevant (1) & (20).

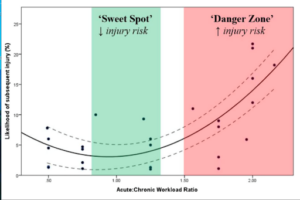

PRGP is effectively an injury to osseous structures due to a reaction (either acute or chronic) which the structures cannot cope with; effectively it is a Bone Stress Injury (BSI) (21). Incorporating a more holistic view of athlete health could well mitigate the progression of a BSI, with gut health emerging as an important risk factor for BSI (22). Monitoring of training load is a complex process, with an element of chronic training load being argued by Gabbett (2016) (23) to avoid injuries from acute increases in load encountered by athletes; for example, during an intense competition schedule such as during a championship. Gabbett (2016) (23) argues for a so-called “sweet-spot” for acute:chronic workload ratio to avoid injury (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Likelihood of Subsequent Injury versus Acute:Chronic Workload Ratio (Gabbett TJ 2016) (23)

A small sample of Australian rules football players, with a clinical diagnosis of PRGP, underwent bone biopsy of an area of the superior pubic ramus which was previously identified from Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) as a region with Bone Marrow Oedema (BMO). New woven bone was found, but poor study methodology did not allow for the researchers to conclude if this new woven bone was pathology related to a stress reaction of the bone, or part of the normal adaptation from training load (24).

The following video summaries some key concepts such as Wolff’s Law, types of bone loading and rate of bone loading relating to BSI:

DPT 7120 Chapter 2 Bone Stress Injuries YouTube (25)

Treatment for PRGP, particularly in relation to the BSI, necessitates unloading of the area followed by graduated return to loading over three to four months (26). Whilst no weight-bearing activities involving running are allowed for three months, stationary cycling can gradually be introduced prior to carefully monitored return to running (26) & (27) . Whilst there is no evidence-based treatment for PRGP, it is possible that interventions for ARGP, with greater evidence-base, could be used as part of the clinical reasoning in rehabilitating PRGP (28), (29), (30), (31), (32), (33), (34), (35) & (36). The Copenhagen Hip and Groin Outcome Score (HAGOS) (37) is a potentially useful tool to monitor athletes’ progress. For those athletes wanting to return to sport the Strategic Assessment of Risk and Risk Tolerance (StARRT) Framework established in 2016 (38) could be a good starting point for making return to play decisions post PRGP. Some sports with repetitive actions, such as bowling in cricket, havee the potential to overload numerous structures and therefore specific interventions for prevention are needed (39).

Conclusions

- PRGP is difficult to diagnose and manage.

- HAGOS is a valid tool to monitor PRGP rehabilitation.

- Most efficacious treatment for PRGP is undefined.

Acknowledgements: Thank you to the Association Chartered Physiotherapists in Sports and Exercise Medicine @physiosinsport and British Journal of Sports Medicine @BJSM_BMJ for their support in publishing this Blog.

Competing Interests: None

Author:

Jim Scanlan NHS Fife Advanced Practitioner Physiotherapist in General Practice

Scottish Rugby Union Faculty of Medicine Member; SCRUMCAPS Tutor.

MSc; BSc (Hons); Pg Dip Ortho Med; Pg Dip Injection Therapy; IRMER Certified;

HCPC; MCSP; ACPSEM: Silver Accreditation.

Twitter: @jim_physio

References

(1) Weir A, Brukner P, Delahunt E, et al. Doha agreement meeting on terminology and definitions in groin pain in athletes. Br J Sports Med 2015;49:768-74. DOI: https://doi:10.1136/bjsports-2015-094869

(2) Hagglund M, Walden M, Ekstrand J. Previous injury as a risk factor for injury in elite football: a prospective study over two consecutive seasons. Br J Sports Med 2006;40:767–72. DOI: https://10.1136/bjsm.2006.026609

(3) Whittaker JL, Small C, Maffey L, et al. Risk factors for groin injury in sport: an updated systematic review. Br J Sports Med 2015;0:1–8 DOI: https://10.1136/bjsports-2014-094287

(4) Werner J, Hagglund M, Walden M, et al. UEFA injury study: a prospective study of hip and groin injuries in professional football over seven consecutive seasons. Br J Sports Med 2009;43:1036–40. DOI: https://10.1136/bjsm.2009.066944

(5) Ekstrand J, Hagglund M, Walden M. Epidemiology of muscle injuries in professional football (soccer). Am J Sports Med 2011;39:1226–32. DOI: https://10.1177/0363546510395879

(6) Anderson DD, Chubinskaya S, Guilak F, et al. Post-traumatic osteoarthritis: improved understanding and opportunities for early intervention. J Orthop Res 2011;29:802–9. DOI: https://10.1002/jor.21359

(7) Arnason A, Sigurdsson SB, Gudmundsson A, et al. Risk factors for injuries in football. Am J Sports Med 2004;32(1 Suppl):5S–16S. DOI: https://10.1177/0363546503258912

(8) Crow JF, Pearce AJ, Veale JP, et al. Hip adductor muscle strength is reduced preceding and during the onset of groin pain in elite junior Australian football players. J Sci Med Sport 2010;13:202–4. DOI: https://10.1016/j.jsams.2009.03.007

(9) Ibrahim A, Murrell GA, Knapman P. Adductor strain and hip range of movement in male professional soccer players. J Orthop Surg 2007;15:46–9. DOI: https://10.1177/230949900701500111

(10) Witvrouw E, Danneels L, Asselman P, et al. Muscle flexibility as a risk factor for developing muscle injuries in male professional soccer players. A prospective study. Am J Sports Med 2003;31:41–6. DOI: https://10.1177/03635465030310011801

(11) Eirale C, Tol JL, Whiteley R, et al. Different injury pattern in goalkeepers compared to field players: a three-year epidemiological study of professional football. J Sci Med Sport 2014;17:34–8. DOI: https://10.1016/j.jsams.2013.05.004

(12) Engebretsen AH, Myklebust G, Holme I, et al. Intrinsic risk factors for groin injuries among male soccer players: a prospective cohort study. Am J Sports Med 2010;38:2051–7. DOI: https://10.1177/0363546510375544

(13) Hagglund M, Walden M, Ekstrand J. Injuries among male and female elite football players. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2009;19:819–27. DOI: https://10.1111/j.1600-0838.2008.00861.x

(14) Paajanen H, Ristolainen L, Turunen H, et al. Prevalence and etiological factors of sport-related groin injuries in top-level soccer compared to non-contact sports. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2011;131:261–6. DOI: https://10.1007/s00402-010-1169-1

(15) O’Connor D. Groin injuries in professional rugby league players: a prospective study. J Sports Sci 2004;22:629–36. DOI: https://10.1080/02640410310001655804

(16) Orchard J, Wood T, Seward H, et al. Comparison of injuries in elite senior and junior Australian football. J Sci Med Sport 1998;1:83–8. DOI: https://10.1016/s1440-2440(98)80016-9

(17) Emery CA, Meeuwisse WH. Risk factors for groin injuries in hockey. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2001;33:1423–33. DOI: https://10.1097/00005768-200109000-00002

(18) Tyler TF, Nicholas SJ, Campbell RJ, et al. The association of hip strength and flexibility with the incidence of adductor muscle strains in professional ice hockey players. Am J Sports Med 2001;29:124–8. DOI: https://10.1177/03635465010290020301

(19) Mountjoy M, Ackerman K, Bailey DM, et al. 2023 International Olympic (IOC) consensus statement on Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (REDs). Br J Sports Med 2023;57:1073-97. DOI: https://10.1136/bjsports-2023-106994

(20) Drew MK, Osmotherly PG and Chiarelli PE. Imaging and Clinical tests for the diagnosis of long-standing groin pain in athletes. A systematic review. Physical Therapy in Sport 2014;15(2):124-29. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ptsp.2013.11.002

(21) Song SH, Koo JH. Bone Stress Injuries in Runners: a Review for Raising Interest in Stress Fractures in Korea. Journal of Korean medical science 2020;35(8):e38. DOI: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4179-3217

(22) Hamstra-Wright KL, Huxel Biven KC, and Napier C. Training Load Capacity, Cumulative Risk, and Bone Stress Injuries: A Narrative Review of a Holistic Approach. Frontiers in Sports and Active Living 2021;3:665683. DOI: https://10.3389/fspor.2021.665683

(23) Gabbett TJ. The training-injury prevention paradox: should athletes be training smarter and harder? Br J Sports Med 2016;50:273-280. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2015-095788

(24) Verrall GM, Henry L, Fazzalari NL, et al. Bone biopsy of the parasymphyseal pubic bone region in athletes with chronic groin injury demonstrates new woven bone formation consistent with a diagnosis of pubic bone stress injury. Am J Sports Med 2008;36(12):2425–31. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/0363546508324690

(25) DPT 7120 (2020) Bone Stress Injuries. 16 June 2020. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Nw-DGdTp-u4

(Accessed: 15 October 2023).

(26) Verrall GM, Slavotinek JP, Fon GT, et al. Outcome of conservative management of athletic chronic groin injury diagnosed as pubic bone stress injury. Am J Sports Med 2007;35(3):467–74. DOI: https://10.1177/0363546506295180

(27) Almeida MO, Silva BNG, Andriolo RB, et al. Conservative interventions for treating exercise-related musculotendinous, ligamentous and osseous groin pain (Review). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2013;6. Art. No.: CD009565. DOI: https://10.1002/14651858.CD009565.pub2

(28) Bisciotti GN, Chamari K, Cena E, et al. The conservative treatment of longstanding adductor-related groin pain syndrome: a critical and systematic review. Biol Sport 2020;38(1):45-63. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5114/biolsport.2020.97669

(29) Mosler AB, Weir A, Eirale C, et al. Epidemiology of time loss groin injuries in a men’s professional football league: a 2-year prospective study of 17 clubs and 606 players. Br J Sports Med 2018;52(5):292–97. DOI: https://10.1136/bjsports-2016-097277

(30) Werner J, Hagglund M, Walden M, et al. UEFA injury study: a prospective study of hip and groin injuries in professional football over seven consecutive seasons. Br J Spots Med 2009;43(13):1036-40. DOI: https://10.1136/bjsm.2009.066944

(31) Taylor R, Vuckovic Z, Mosler A, et al. Multidisciplinary Assessment of 100 Athletes With Groin Pain Using the Doha Agreement: High Prevalence of Adductor-Related Groin Pain in Conjunction With Multiple Causes. Clin J Sport Med 2018;28(4):364-69. DOI: https://10.1097/JSM.0000000000000469

(32) Serner A, van Eijck CH, Beumer BR, et al. Study quality on groin injury management remains low: a systematic review on treatment of groin pain in athletes. Br J Sports Med 2015;49:813-24. DOI: https://10.1136/bjsports-2014-094256

(33) Holmich P, Uhrskou P, Ulnits L, et al. Effectiveness of active physical training as treatment for long-standing adductor-related groin pain in athletes: randomised trial. The Lancet 1999;353:439-43. DOI: https://10.1016/S0140-6736(98)03340-6

(34) Yousefzadeh A, Shadmehr A, Olyaei GR, et al. Effect of Holmich protocol exercise therapy on long-standing adductor-related groin pain in athletes: an objective evaluation. BMJ Open Sport & Exercise Medicine 2018;4:e000343. DOI: https://0.1136/bmjsem-2018-000343

(35) Haroy J, Clarsen B, Wiger EG, et al. The Adductor Strengthening Programme prevents groin problems among male football players: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Br J Sports Med 2019;53:145-52. DOI: https://10.1136/bjsports-2017-098937

(36) King E, Franklyn-Miller A, Richter, C, et al. Clinical and biomechanical outcomes of rehabilitation targeting intersegmental control in athletic groin pain: prospective cohort of 205 patients. Br J Sports Med 2018;52:1054-62. DOI: https://10.1136/bjsports-2016-097089

(37) Thorborg K, Holmich P, Christensen R, et al. The Copenhagen Hip and Groin Outcome Score (HAGOS): development and validation according to the COSMIN checklist. Br J Sports Med 2011;45(6):478-91. DOI: https://10.1136/bjsm.2010.080937

(38) Ardern CL, Glasgow P, Schneiders, et al. 2016 Consensus statement on return to sport from the First World Congress in Sports Physical Therapy, Bern. Br J Sports Med 2016;50:853-64. DOI: https://10.1136/bjsports-2016-096278

(39) Scanlan JA. Cricket Scotland Women’s Twenty-20 International Cricket Council World Cup Qualifier: A Pilot Prospective Cohort Injury Study. J Sports Injr Med 2023;7(2):195-203 DOI: https://10.29011/2576-9596.100195