A view from the emergency department – working up lateral ankle injuries from diagnosis to return to play

Ankle sprains affect anyone and everyone along the activity spectrum, from semi-professional players and athletes to weekend warriors and accidental injuries. There are over 300,000 ankle sprain presentations to ED annually in the UK (1), 85% of which, are accounted for by lateral ankle sprains.

Clinical Work Up

The mechanism of injury is a key factor in helping to unpick injury subtypes in the ED. These can be divided into lateral, medial, and high ankle sprains (Table 1).

| Types of Sprains | Mechanism of Injury |

| Lateral Ankle Sprain | Inversion & Plantarflexion |

| Medial Ankle Sprain | Eversion |

| High Ankle Sprain | External rotation & dorsiflexion |

When a case of LAS is suspected in ED, there are many important factors to consider when taking a history (Table 2).

| Risk Factors for LAS |

Extrinsic (2)

|

Intrinsic (2)

|

Table 2: Risk Factors for Lateral Ankle Sprains

Grading a lateral ankle sprain can be challenging, however there may be features in the history that would point towards a higher grade of injury. This may include a combination of factors including participating in high energy contact sports and previous ankle injuries.

Clinical Based Tests

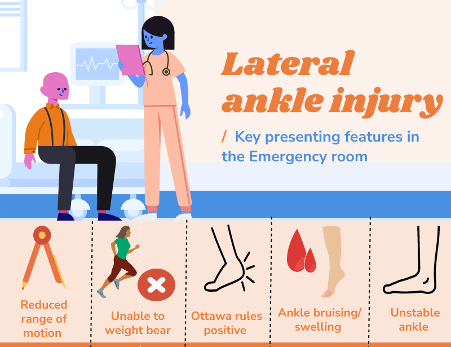

The common clinical features presenting to the ED for a patient with a lateral ankle injury are shown in (Figure 1).

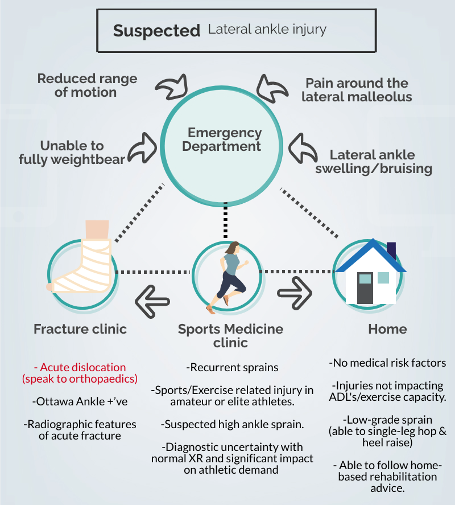

In ED, patients with LAS can be split into two main subgroups:

- Unable to weight bear following an injury

“For patients who can’t weight bear, a visual inspection and palpation using the Ottawa rule can help to rule in patients who need an X-ray. Additional screening tests, should also be performed to assess for syndesmosis, or high ankle injuries, in non-weight bearing patients – or those with bone disorders”

&

- Unstable ankle/ that keeps giving way

“For patients with unstable ankles, it is important to ask about functional or athletic demands, a history of previous ankle injury and special tests to palpate and assess the integrity of the lateral ankle ligaments. If a high-grade lateral ankle ligament injury is suspected, then follow up in a specialist SEM clinic may be needed to consider further imaging” (Figure 2)

On the ED shop floor, a quick screen using symptoms, special tests, and the single leg load test (Table 3), can help to determine which patients can be sent home without follow up. The single leg load test can be performed easily on the shop floor and being able to reach stage 3 or 4 is associated with not having a high-grade lateral ankle injury (4).

| Stage 1 | Difficulty in single leg standing |

| Stage 2 | Able to single-leg stand |

| Stage 3 | Able to single-leg heel raise |

| Stage 4 | Able to single leg hop |

If significant swelling, bruising or pain limits examination, then a repeat examination in 1 week in a specialist follow up clinic, may be advisable. This is based on the idea that as pain and swelling, reduce after the acute injury – the sensitivity and specificity of clinic-based tests improves (Table 4). Immobilisation may be considered in patients where a high-grade LAS, or syndesmosis injury is suspected, up until this review.

| Structure | Test | Specificity | Sensitivity |

| Lateral Ankle | |||

| ATFL | Anterior draw | 0.84 | 0.96 (5) |

| CFL | Talar tilt | 0.75 | 0.67 (6) |

| PTFL | Posterior draw | ||

| Medial Ankle | |||

| Deltoid | Eversion stress | 5 days post injury: 0.84 | 5 days post injury: 0.96 |

| High ankle | |||

| Syndesmosis | Kleiger (external rotation) | 0.85 | 0.20 (7) |

| Syndesmosis | Squeeze | 0.94 | 0.30 (7) |

Table 4: Sensitivity and specificity of common clinical tests of the ankle

What can a Sport and Exercise medicine clinics offer follow up patients from the ED?

- Repeat examination, in a follow up clinic – focussed on function and rehabilitation.

- Point of care ultrasound (with dynamic testing) to evaluate the ankle ligaments and assess ankle stability.

ATFL: https://vimeo.com/692781151

CFL: https://vimeo.com/692781290

AITFL: https://vimeo.com/692783171

- Opportunity to establish early rehab goals and timeline of recovery.

- Referral for targeted imaging (US or MRI) – where required (Table 5).

| Advantages | Disadvantages | |

| Ultrasound | Dynamic views may be obtained

Cost effective Time-efficient (8) |

Reliant on clinician expertise

Reliant on equipment used

|

| MRI | Particularly useful in chronic ankle instability or persisting symptoms

Useful in concomitant injuries |

Expensive

Limited availability False-positive findings (3) |

Table 5: Ultrasound vs MRI imaging for lateral ankle injuries

Conclusion

- The single leg loading test, can be used as a screening test on the ED shop floor, to assess ankle function.

- The sensitivity and specificity of ankle tests, improves after swelling and pain reduces from an acute injury.

- Follow up in a specialist Sports medicine clinic from ED, can help to improve access to imaging and early rehabilitation

No competing interest and no relevant declarations.

Authors

Kos Desilva @DesilvaKos

Sports & Exercise Medicine department, Homerton University Hospital Foundation Trust, London, United Kingdom

Irfan Ahmed @Exerciseirfan

Sports & Exercise Medicine department, Homerton University Hospital Foundation Trust, London, United Kingdom

With thanks to:

Ultrasound video of the lateral ankle provided by Orca Resource & Peter Resteghini.

Orca Resource EdTech streaming platform provides a comprehensive series of high quality videos for the medical industry including musculoskeletal ultrasound

Dr. Peter Resteghini is a Consultant Physiotherapist & Musculoskeletal Sonographer based at Homerton Hospital NHS trust.

He is also the Course Director for the Postgraduate Certificate in Musculoskeletal Ultrasound (University of East London)

References

- Ferran, N.A. and Maffulli, N. (2006). Epidemiology of Sprains of the Lateral Ankle Ligament Complex. Foot and Ankle Clinics, [online] 11(3), pp.659–662. Available at: https://www.foot.theclinics.com/article/S1083-7515(06)00063-5/fulltext [Accessed 20 Jan. 2022].

- Vuurberg, G., Hoorntje, A., Wink, L.M., van der Doelen, B.F.W., van den Bekerom, M.P., Dekker, R., van Dijk, C.N., Krips, R., Loogman, M.C.M., Ridderikhof, M.L., Smithuis, F.F., Stufkens, S.A.S., Verhagen, E.A.L.M., de Bie, R.A. and Kerkhoffs, G.M.M.J. (2018). Diagnosis, treatment and prevention of ankle sprains: update of an evidence-based clinical guideline. British Journal of Sports Medicine, [online] 52(15), pp.956–956. Available at: https://bjsm.bmj.com/content/52/15/956.long [Accessed 20 Jan. 2022].

- Halabchi, F. and Hassabi, M. (2020). Acute ankle sprain in athletes: Clinical aspects and algorithmic approach. World Journal of Orthopedics, [online] 11(12), pp.534–558. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7745493/ [Accessed 20 Jan. 2022].

- Noda, Y., Horibe, S., Hiramatsu, K., Takao, R. and Fujita, K. (2021). Quick and simple test to evaluate severity of acute lateral ankle sprain. Asia-Pacific Journal of Sports Medicine, Arthroscopy, Rehabilitation and Technology, [online] 25(30), pp.30–34. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8180947/ [Accessed 20 Jan. 2022].

- Delahunt, E., Bleakley, C.M., Bossard, D.S., Caulfield, B.M., Docherty, C.L., Doherty, C., Fourchet, F., Fong, D.T., Hertel, J., Hiller, C.E., Kaminski, T.W., McKeon, P.O., Refshauge, K.M., Remus, A., Verhagen, E., Vicenzino, B.T., Wikstrom, E.A. and Gribble, P.A. (2018). Clinical assessment of acute lateral ankle sprain injuries (ROAST): 2019 consensus statement and recommendations of the International Ankle Consortium. British Journal of Sports Medicine, [online] 52(20), pp.1304–1310. Available at: https://bjsm.bmj.com/content/52/20/1304 [Accessed 20 Jan. 2022].

- Wenning, M., Gehring, D., Lange, T., Fuerst-Meroth, D., Streicher, P., Schmal, H. and Gollhofer, A. (2021). Clinical evaluation of manual stress testing, stress ultrasound and 3D stress MRI in chronic mechanical ankle instability. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders, [online] 22(1). Available at: https://bmcmusculoskeletdisord.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12891-021-03998-z [Accessed 20 Jan. 2022].

- de César, P.C., Ávila, E.M. and de Abreu, M.R. (2011). Comparison of Magnetic Resonance Imaging to Physical Examination for Syndesmotic Injury after Lateral Ankle Sprain. Foot & Ankle International, [online] 32(12), pp.1110–1114. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22381194/ [Accessed 20 Jan. 2022].

- Esmailian, M., Ataie, M., Ahmadi, O., Rastegar, S. and Adibi, A. (2021). Sensitivity and specificity of ultrasound in the diagnosis of traumatic ankle injury. Journal of Research in Medical Sciences : The Official Journal of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, [online] 26(14), p.14. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8106407/ [Accessed 20 Jan. 2022].