Why develop a new muscle injury classification?

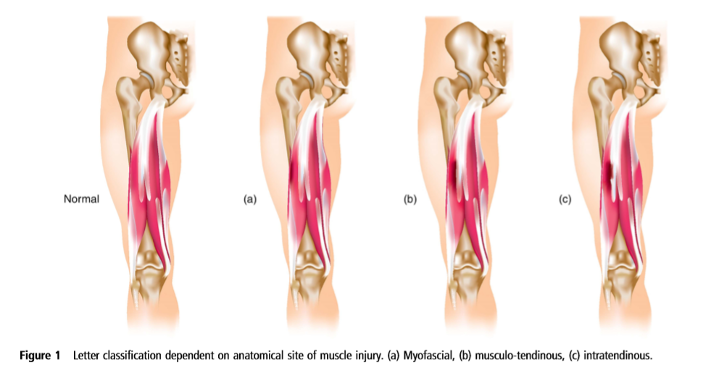

The British Athletics Muscle Injury Classification (BAMIC) was developed in 2014 as part of a hamstring strategy.[1] An internal report in our elite track and field squad established that hamstring injury was the leading cause of missed time from training and competition. The muscle injury grading systems available at that time, had a lack of consistency in terminology and lack of clarity regarding diagnostic entities. In particular, the modified Peetron’s grading system and the Munich consensus did not acknowledge injury to the intramuscular tendon.[2,3] We considered that due to different healing processes within muscular and tendon tissue that outcomes and ideal management may be different depending on the injured structure. The British Athletics Muscle Injury Classification (BAMIC) was developed and is an MRI based diagnostic system, detailing the severity (grades 0–4) and site of injury (myofascial(a), muscle-tendon junction (b) or intratendinous (c). (Figure 1)[1]

What we have learnt from the application of the BAMIC system

The BAMIC system has been applied in both our own and other elite sport settings.

British Athletics outcomes

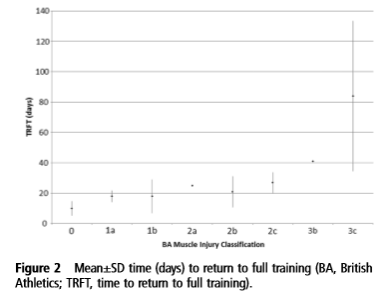

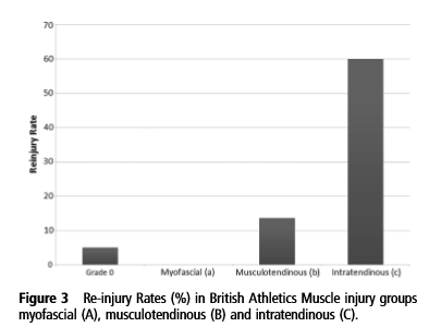

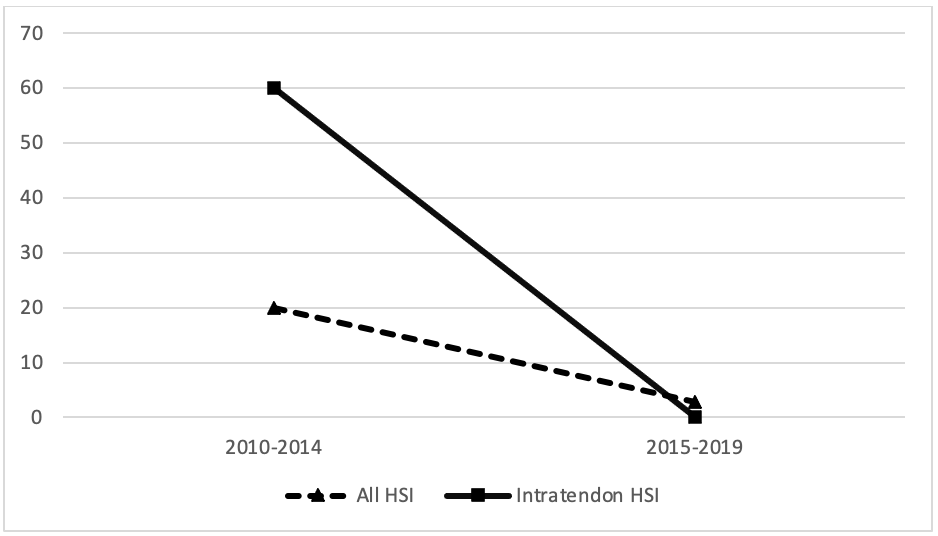

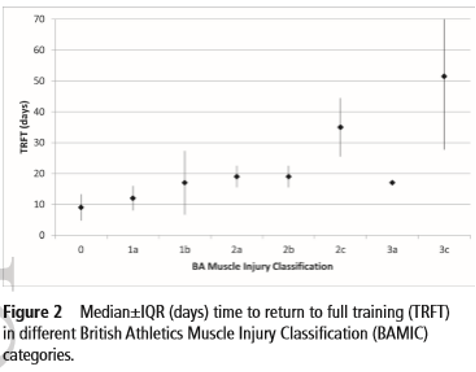

A retrospective study in our track and field group demonstrated time to return to full training (TRFT) was delayed and recurrence rate higher in intratendinous (‘c’) acute hamstring injuries.(Figures 2, 3 and 4)[4] Therefore the recognition and categorisation of intratendon injuries was considered to be important and strategies developed with the intention of improving the rehabilitation and outcomes of these injuries.

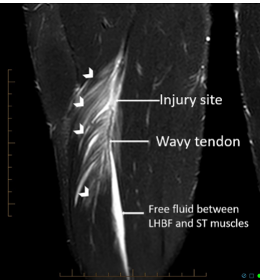

Subsequent studies in elite professional Australian Rules Football[5], football[6–8] and elite rugby[9] have demonstrated significantly longer time to return to play in ‘c’ hamstring injuries. The loss of tension and waviness within the tendon in this type of injury appears most relevant to outcome. However, in a recent study in elite English football, 2c hamstring injuries (i.e. those without loss of tension) were not associated with increased time to RTP or reinjury.[10] These studies also demonstrate the success of non-surgical rehabilitation in intratendon injuries, including high grade 3c intratendon injuries.

How we developed a new way of doing things

A specific and targeted rehabilitation strategy for hamstring injuries, particularly intratendon injuries, based on our classification system was developed.[11] We applied knowledge of both muscle and tendon healing physiology to identify appropriate rehabilitation strategies.(Figure 5) Please note that the suggested healing times in Figure 4 relate to tissue healing and not direct clinical or functional recovery. It is well established that full tissue healing and normal imaging is not required for clinical recovery.[12,13] The principles we applied in rehabilitation included shared decision making with coaches and athletes, nutritional strategies to support healing and an individualised risk factor review. Targeted strengthening programmes were applied for specific injuries. In high grade intratendon injuries, we considered that initial limitation of eccentric contractions and running speed, which produce higher strains on the tendon, was important, before then applying appropriate loads to support tendon healing and adaptation. In all rehabilitations, progressive return to functional movements and high speed running was essential.

Our implementation of the classification system and the principles of rehabilitation helped to: improve the recognition of injuries associated with higher recurrence rates, provide a common language to enhance communication between all stakeholders, facilitate a shared decision making process based on risk between the coach, athlete and support staff and target rehabilitation to the injured tissue and for a specific goal.

What was the outcome?

We recently published our recent hamstring injury outcomes following implementation of our management strategy.[14] We noted a re-injury rate of 2.9% which compares favourably with other published epidemiological studies and our previous work.(Figure 6) Importantly the average TRFT for most injury classes, with the exception of 2c injuries which increased by 1 week, were not higher, demonstrating that our reduced re-injury rates were not caused by simply taking a more cautious approach.(Figures 2 and 7) Our recent work also demonstrated that tendon cross-sectional area involvement and loss of tension was associated with longer TRFT, and longitudinal splits were less important which may be important in future development of the BAMIC system. Our work in hamstring injuries over the last decade has confirmed to us that excellent functional outcomes, including return to medal winning track and field performances at global championships, is reliably possible with rehabilitation and without surgery, even in high grade injuries that involve intramuscular tendons.

Conclusion

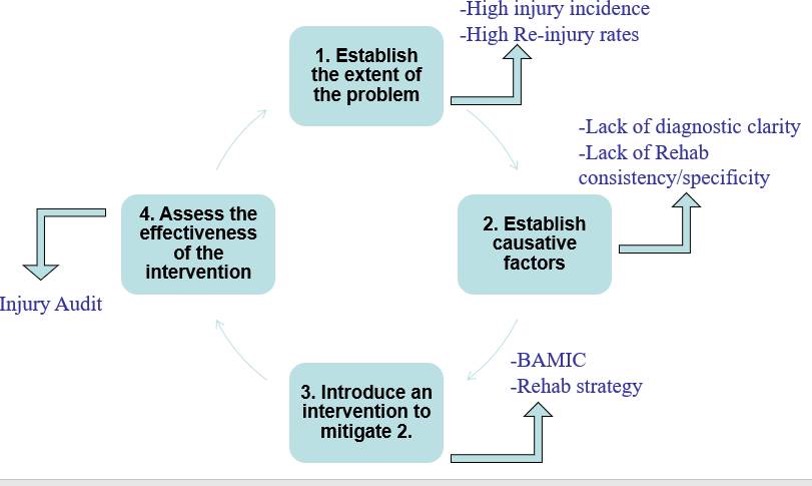

The outcomes in our most recent paper come from working through the van Mechelen ‘sequence of prevention model’ (Fig.8). In this the problem was identified, a potential solution was developed and implemented and its effectiveness was evaluated.[15,16] The use of the BAMIC in elite sporting populations, where the demand on the muscle-tendon unit is significantly greater compared to non-elite populations, indicate that injuries involving intratendon injuries may require longer to successfully return to play than muscular injuries. The rehabilitation of different injuries may be optimised with targeted strategies including exercise prescription and appropriate time for recovery. Further research is required to investigate the clinical correlates of intramuscular tendon injury as these may be difficult to detect clinically[17] and the role of surgery in high grade 3c and 4c injuries is still to be determined. The BAMIC system can help to inform effective decision making on RTP/RTFT and rehabilitation progression.

Take Home Messages:

- Implement a strategic approach to reduce the impact of high burden injuries in your sport

- In muscle injury the BAMIC can enable a common language for stakeholders and identify injuries that require a targeted rehabilitation approach

- High grade intramuscular tendon injuries, in a well-motivated athlete with a structured rehabilitation plan, can return to the highest level of competitive and high demand sport with non-surgical management

- Clinical symptoms and signs of intramuscular tendon injury and the indications for surgery in these injuries requires further research

Authors and Affiliations:

Ben MacDonald1, Michael Giakoumis2, Noel Pollock2,3

1 Wolverhampton Wanderers Football Club, Wolverhampton, UK

2 British Athletics, London, UK

3 Institute of Sport, Exercise and Health, University College London, UK

References:

1 Pollock N, James SLJ, Lee JC, et al. British athletics muscle injury classification: a new grading system. Br J Sports Med 2014;48:1347–51. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2013-093302

2 Mueller-Wohlfahrt H-W, Haensel L, Mithoefer K, et al. Terminology and classification of muscle injuries in sport: The Munich consensus statement. British Journal of Sports Medicine 2012;47:342–50. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2012-091448

3 Peetrons P. Ultrasound of muscles. Eur Radiol 2002;12:35–43. doi:10.1007/s00330-001-1164-6

4 Pollock N, Patel A, Chakraverty J, et al. Time to return to full training is delayed and recurrence rate is higher in intratendinous (‘c’) acute hamstring injury in elite track and field athletes: clinical application of the British Athletics Muscle Injury Classification. Br J Sports Med 2016;50:305–10. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2015-094657

5 Eggleston L, McMeniman M, Engstrom C. High-grade intramuscular tendon disruption in acute hamstring injury and return to play in Australian Football players. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports 2020;30:1073–82. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/sms.13642

6 Rushton A, Khurniawan KA, James S, et al. Return to play and recurrence rate following hamstring injury in elite football: use of the British Athletic Muscle Injury Classification. Physiotherapy 2019;105:e45. doi:10.1016/j.physio.2018.11.293

7 van der Made AD, Almusa E, Whiteley R, et al. Intramuscular tendon involvement on MRI has limited value for predicting time to return to play following acute hamstring injury. Br J Sports Med 2018;52:83–8. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2017-097659

8 Shamji R, James SLJ, Botchu R, et al. Association of the British Athletic Muscle Injury Classification and anatomic location with return to full training and reinjury following hamstring injury in elite football. BMJ Open Sport & Exercise Medicine 2021;7:e001010. doi:10.1136/bmjsem-2020-001010

9 Biglands JD, Grainger AJ, Robinson P, et al. MRI in acute muscle tears in athletes: can quantitative T2 and DTI predict return to play better than visual assessment? Eur Radiol 2020;30:6603–13. doi:10.1007/s00330-020-06999-z

10 McAuley S, Dobbin N, Morgan C, et al. Predictors of time to return to play and re-injury following hamstring injury with and without intramuscular tendon involvement in adult professional footballers: A retrospective cohort study. J Sci Med Sport 2021;:S1440-2440(21)00457-6. doi:10.1016/j.jsams.2021.10.005

11 Macdonald B, McAleer S, Kelly S, et al. Hamstring rehabilitation in elite track and field athletes: applying the British Athletics Muscle Injury Classification in clinical practice. Br J Sports Med 2019;53:1464–73. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2017-098971

12 Reurink G, Goudswaard GJ, Tol JL, et al. MRI observations at return to play of clinically recovered hamstring injuries. Br J Sports Med Published Online First: 19 November 2013. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2013-092450

13 Vermeulen R, Almusa E, Buckens S, et al. Complete resolution of a hamstring intramuscular tendon injury on MRI is not necessary for a clinically successful return to play. Br J Sports Med 2020;:bjsports-2019-101808. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2019-101808

14 Pollock N, Kelly S, Lee J, et al. A 4-year study of hamstring injury outcomes in elite track and field using the British Athletics rehabilitation approach. Br J Sports Med Published Online First: 14 April 2021. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2020-103791

15 Van Tiggelen D, Wickes S, Stevens V, et al. Effective prevention of sports injuries: a model integrating efficacy, efficiency, compliance and risk-taking behaviour. Br J Sports Med 2008;42:648–52. doi:10.1136/bjsm.2008.046441

16 van Mechelen W, Hlobil H, Kemper HC. Incidence, severity, aetiology and prevention of sports injuries. A review of concepts. Sports Med 1992;14:82–99. doi:10.2165/00007256-199214020-00002

17 Crema MD, Guermazi A, Reurink G, et al. Can a Clinical Examination Demonstrate Intramuscular Tendon Involvement in Acute Hamstring Injuries? Orthop J Sports Med 2017;5:2325967117733434. doi:10.1177/2325967117733434