What is the problem?

Sports injury monitoring systems have adopted an increasingly scientific approach to monitoring players’ health through standardised consensus-based guidelines.1 2 Within these systems, athletes are usually instructed to report their injuries based on a delineated injury definition. Then medical staff review the data and determine the required necessary actions. Yet, injury monitoring systems are also ongoing clinical processes that enhance the athlete’s injury management through interaction between all the team members; athletes, coaches and medical practitioners. Following this perspective, there are two main drivers of an injury monitoring system. Firstly, the engagement of all the stakeholders and secondly, the development and fostering of a culture conducive to its implementation.3 This brings us to the question: what role do we, as medical practitioners, have in creating this supportive environment towards user engagement?

Our role as leaders

In developing a supportive culture towards engaging all users with an injury monitoring system, our role as medical practitioners needs to extend beyond the provision of athlete care ‘on demand’. It is our role to engage all the team members and work unitedly in delivering the optimum management for the athlete. To successfully navigate this transition, we need to embody our leadership skills.4

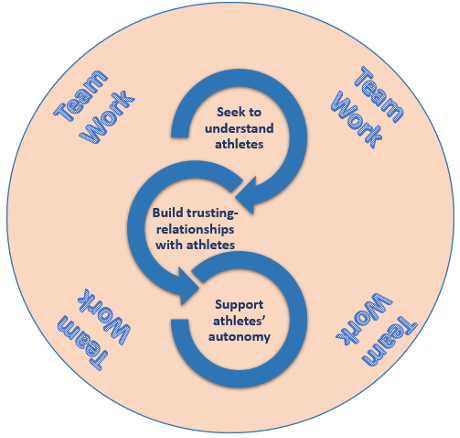

The kind of leadership required is one that enables us to foster an environment whereby, as a team, we:

- Seek to understand athletes’ perceptions of injuries

In the words of Bolling et al. (2018),5, if we want a good wine, we need to harvest the best grapes. In this sense, to develop injury risk mitigation measures relevant to our athletes, we need to start with addressing their injury problem in their context. Therefore, as leaders, we need to listen and validate our athlete’s perception of injuries and their consequences through their ‘eyes’. In doing so, we can obtain meaningful athlete injury data from an injury monitoring system. This will allow us to communicate with athletes through a common language.6

- Build trusting relationships with athletes

Giving a voice to our athletes also serves as an opportunity to build trusting relationships. Our athletes must trust that we have their best interest in mind, value their autonomy and privacy, and care about them as social individuals, and not just team members. This can take place out of the clinic room. For instance, by spending time and having a laugh with them during or after meals or whilst travelling.7 8 Establishing a trusting relationship provides an excellent opportunity to increase athletes’ confidence and willingness in reporting their health problems to us. 9 This allows us to engage all the multidisciplinary staff in the athlete’s care from the early onset of an injury, which may mitigate the risks of further consequences.

- Support athletes’ autonomy

Sports injury prevention is a learning process for athletes and ourselves.10 As leaders in our team, we need to learn how to support our athletes’ autonomy. Our role is to engage athletes in the shared-decision making about reporting health problems. We also need to supply them with the necessary support and information to help them navigate the pros and cons in making decisions regarding risks.9 This process enhances their autonomy. In addition, more positive outcomes in maintaining their engagement with the injury monitoring system can be expected3, because they feel volition in their choices.

Take-home point

We need to inspire a shared team vision in optimising the health of our athletes. As leaders within our team, we can create a supportive environment enhancing engagement with an injury monitoring system. This shared vision is based on understanding our athletes’ perceptions of injuries, allowing us to build trusting relationships with athletes in ways that enhances their autonomy.

Authors

Sandro Vella1 2, Caroline Bolling3 , Evert Verhagen3, Isabel Sarah Moore1

- Cardiff School of Sport and Health Sciences, Cardiff Metropolitan University, Cardiff, UK

- Malta Football Association, Millenium Stand, National Stadium, Ta’ Qali ATD 4000, Malta

- Amsterdam Collaboration for Health and Safety in Sports, Department of Public and Occupational Health, Amsterdam Public Health Research Institute, VU University Medical Center, Van der Boechorstraat 7, 1081 BT Amsterdam, The Netherlands

Conflict of interest: ISM is an Associate Editor for the British Journal of Sports Medicine

References

- Fuller C W, Ekstrand J, Junge A, et al. Consensus statement on injury definitions and data collection procedures in studies of football (soccer) injuries. British Journal of Sports Medicine2006;40:193-201 doi:1136/bjsm.2005.025270

- Bahr R, Clarsen B, Wayne D, et al. International Olympic Committee consensus statement: methods for recording and reporting epidemiological data on injury and illness in sport 2020 (including STROBE Extension for Sports Injury and Illness Surveillance (STROBE- SIIS)). British Journal of Sports Medicine 2020;54:372–389. doi:1136/bjsports-2019-101969

- Saw, A., Kellmann, M., Main, L. C., et al. Athlete Self-Report Measures in Research and Practice: Considerations for the Discerning Reader and Fastidious Practitioner. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance. 2017;12,127–135 doi:10.1123/ijspp.2016-0395

- Verhagen E, Mellette J, Konin J, et al. Taking the lead towards healthy performance: the requirement of leadership to elevate the health and performance teams in elite sports. British Medical Journal Open Sport & Exercise Medicine. 2020;0: e000834. doi:1136/ bmjsem-2020-000834

- Bolling C, van Mechelen W, Pasman H, et al. Context Matters: Revisiting the First Step of the ‘ Sequence of Prevention ’ of Sports Injuries. Sports Medicine 2018;48(10): 2227-223 doi: 10.1007/s40279-018-0953-x

- Bolling C, Delfino Barboza S, van Mechelen W, et al. How elite athletes, coaches, and physiotherapists perceive a sports injury. Translational Sports Medicine 2018;1:17–73. doi:1002/tsm2.53

- Burns L, Weissensteiner M & Cohen M. Supportive interpersonal relationships: A key component to high-performance sport. British Journal of Sports Medicine2019;53(22): 1387-1390. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2018-100312

- Thornton J S. Athlete autonomy, supportive interpersonal environments and clinicians’ duty of care; as leaders in sport and sports medicine, the onus is on us: the clinicians. British Journal of Sports Medicine2020;54:71-72. doi: 1136/bjsports-2019-100783

- Tayne S, Hutchinson M R, O’Connor F G, et al. Leadership for the Team Physician. Current Sports Medicine Reports 2020;19(3): 119-123. doi:1249/JSR.0000000000000696

- Bolling C, Delfino Barboza S, van Mechelen W, et al. Letting the cat out of the bag: athletes, coaches and physiotherapists share their perspectives on injury prevention in elite sports. British Journal of Sports Medicine2020;54:871-877. doi:1136/bjsports-2019-100773