The three-line summary

- The number of new weekly COVID-19 cases in professional rugby appears to be related to community COVID-19 cases.

- When community prevalence is increased, more professional rugby players are likely to have COVID-19.

- Reducing the interactions that professional rugby players and their households have with the wider community may be required during periods of increased COVID-19 prevalence.

What is the issue?

During the COVID-19 pandemic, professional and recreational sports were postponed in the UK.[1] Professional sport returned first, followed by recreational sport, both implementing risk management and mitigation strategies.[2][3]

Sports are tasked with managing and mitigating COVID-19 spread within their clubs. The risks of virus transmission exist beyond the specific sporting activity,[4] including associated social interactions and travel. COVID-19 within the wider community also poses a risk. Elite athletes likely have a limited number of interactions with individuals not in their team, given their day-to-day sporting commitments, although their family and household members may still interact within the wider community (e.g., work and education). They may also undertake daily activities, such as shopping. The association between COVID-19 cases in the community and sport has yet to be evaluated, which may help the implementation of evidence-informed risk mitigation strategies.

COVID-19 Population Prevalence vs. Rugby Prevalence – how did we get the data?

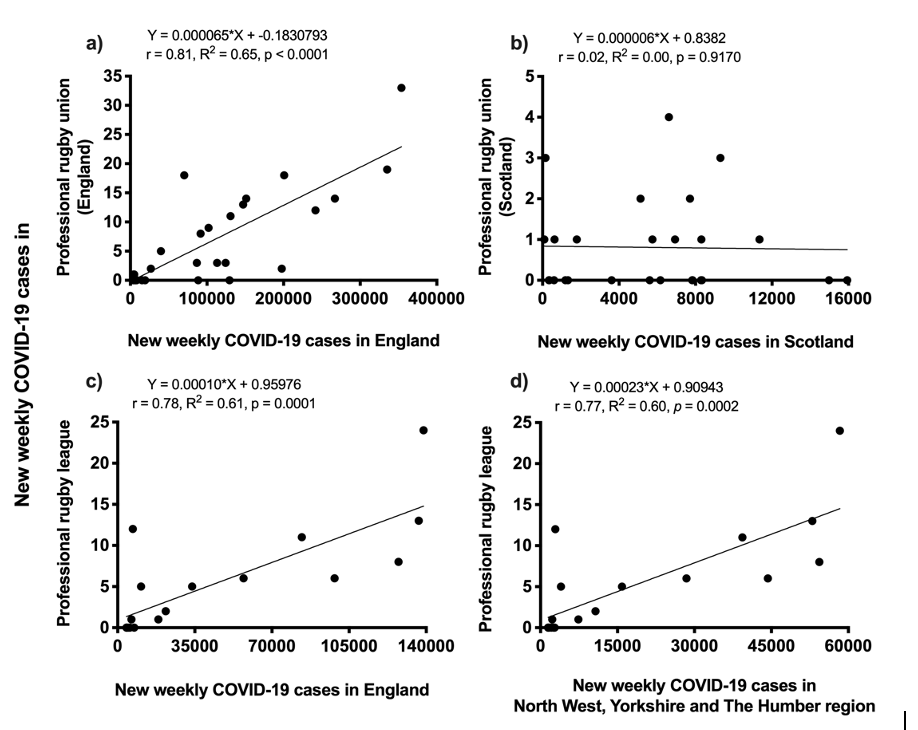

To determine the association between new weekly COVID-19 cases in the community and in professional rugby, new weekly COVID-19 cases within professional rugby were compared with national (England or Scotland) or regional (North West, Yorkshire and the Humber for rugby league only due to geographic location of teams) new weekly cases (https://coronavirus.data.gov.uk) for the same time period. Professional data were from rugby league (Super League [excluding the team based in France]; n=10 teams; w/c 6/7/20–1/11/20) and rugby union in Scotland (n=2 teams; w/c 13/7/20–11/1/21), and England (n=12 teams; w/c 6/7/20–18/1/21) were used.

The number of new positive cases were reported weekly (Monday – Sunday). Positive COVID-19 cases were identified via routine weekly reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) screening for asymptomatic individuals, or RT-PCR tests for symptomatic individuals, reported to the respective governing body.

New positive cases within rugby were subtracted from new weekly COVID-19 community cases, to avoid mathematical coupling between data sets when determining correlations.[5]

Associations were calculated via Pearson correlation coefficients (r) and R2, and significance set at p<0.05. Associations (r) were interpreted as <0.1 trivial, 0.1–0.3 small, 0.3–0.5 moderate, 0.5–0.7 large, 0.7–0.9 very large, 0.9–1 nearly perfect, 1 perfect.[6]

What did we find?

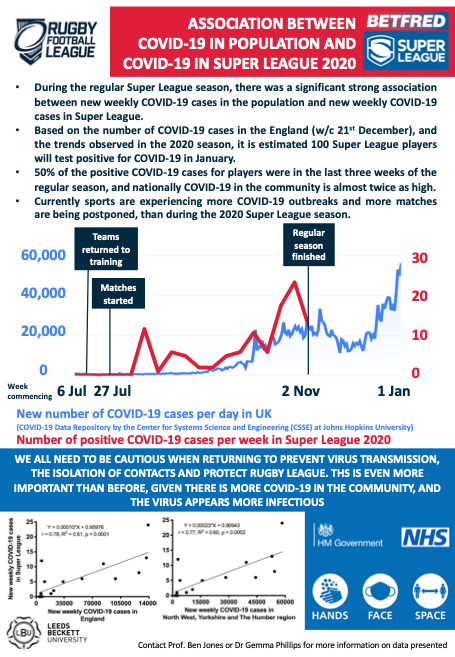

Very large and significant (p < 0.001) associations were observed between new weekly COVID-19 cases in professional rugby (league and union) and the community in England (Figure 1a, 1b), and professional rugby league and regional data (Figure 1d). A trivial association was observed between new weekly COVID-19 cases in professional rugby union and the community in Scotland (Figure 1b).

What does this mean?

The associations between new weekly COVID-19 cases in the community and in professional rugby suggest that in England, the COVID-19 prevalence in sport is reflective of the wider community. Even for elite athletes, new weekly cases follow a similar trend to that in the community. This was not the case for Scotland, which may be due to different community (Government initiatives), sport (Governing body) practices, or simply a reflection of the number of teams (n = 2) observed (e.g., small sample size).

The absence of genomic sequencing makes it difficult to determine the proportion of new COVID-19 cases from the rugby environment or wider community. Nevertheless, during periods of high community COVID-19 prevalence, extra care should be taken by sports.

These data can also be used to support the education of club staff and players, demonstrating their vulnerability to contracting the virus, despite being within COVID-19 (RT-PCR or lateral flow) screening cycles. For example, Figure 2 was shared with Super League clubs by the Rugby Football League on 4/01/21, as they returned to training, following a 6 to 8 week offseason, during a period of high COVID-19 prevalence in the population. Based on the association presented here, it was estimated that 100 positive cases would be observed in January. This was perceived as overzealous at the time, in a population group of approximately 600, when 88 essential staff had previously tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 during the 2020 season (Figure 1c, d). To date (27/01/21), since sharing the infographic, 70 positive COVID-19 cases have been observed in Super League.

Sports can use these data to ensure that they continue during the pandemic, protecting the health of essential staff and supporting the national agenda of reducing COVID-19 in the population and the burden on public health authorities.

Authors and Affiliations:

Ben Jones 1,2,3,4,5, Gemma Phillips 1,2,6, Simon PT Kemp 7,8, Keith A Stokes 7,9, Andy Boyd 10, Richard Wood 10, James Robson 10, Matt Cross 9,11

1 Carnegie Applied Rugby Research (CARR) centre, Carnegie School of Sport, Leeds Beckett University, Leeds, UK

2 England Performance Unit, The Rugby Football League, Leeds, UK

3 Leeds Rhinos Rugby League club, Leeds, UK

4 Division of Exercise Science and Sports Medicine, Department of Human Biology, Faculty of Health Sciences, the University of Cape Town and the Sports Science Institute of South Africa, Cape Town, South Africa

5 School of Science and Technology, University of New England, Armidale, NSW, Australia.

6 Hull Kingston Rovers, Hull, UK

7 Rugby Football Union, Twickenham, UK

8 London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, London, UK

9 University of Bath, Bath, UK

10 Scottish Rugby Union, Murrayfield, UK

11 Premiership Rugby, Twickenham, UK

References:

1: Stokes KA, Jones B, Bennett M, et al. Returning to Play after Prolonged Training Restrictions in Professional Collision Sports. Int J Sports Med Published Online First: 29 May 2020. doi:10.1055/a-1180-3692

2: Kemp S, Cowie CM, Gillett M, et al. Sports medicine leaders working with government and public health to plan a ‘return-to-sport’ during the COVID-19 pandemic: the UK’s collaborative five-stage model for elite sport. Br J Sports Med 2021;55:4–5. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2020-102834

3: Jones B, Phillips G, Kemp S, et al. A Team Sport Risk Exposure Framework to Support the Return to Sport. BJSM Blog – Soc. Medias Lead. SEM Voice. 2020.https://blogs.bmj.com/bjsm/2020/07/01/a-team-sport-risk-exposure-framework-to-support-the-return-to-sport/ (accessed 9 Sep 2020).

4: Jones B, Phillips, G, Kemp, SPT, et al. SARS-CoV-2 transmission during rugby league matches: Do players become infected after participating with SARS-CoV-2 positive players? Br J Sports Med 2021.

5: Pearson K. Mathematical contributions to the theory of evolution.—On a form of spurious correlation which may arise when indices are used in the measurement of organs. Proc R Soc Lond 1897;60:489–98. doi:10.1098/rspl.1896.0076

6: New View of Statistics: Effect Magnitudes. https://www.sportsci.org/resource/stats/effectmag.html (accessed 2 Jan 2021).