There is concern that females take longer to recover than their male counterparts after concussion.1 The evidence, however, is conflicting, with some finding no difference in recovery between the sexes.2 This likely reflects a complex interplay between intrinsic factors, such as biological sex, and extrinsic factors influencing concussion recovery.

How did we do this study

This study was part of the largest cohort study of collegiate athletes to date, the Concussion Assessment, Research and Education (CARE) Consortium Study, including athletes from 30 colleges and universities across the United States.3 Our final study population included 1071 concussions occurring in sports where both single-sex men’s and women’s teams were fielded.

What did we find?

1: Overall, no differences in concussion recovery between sexes:

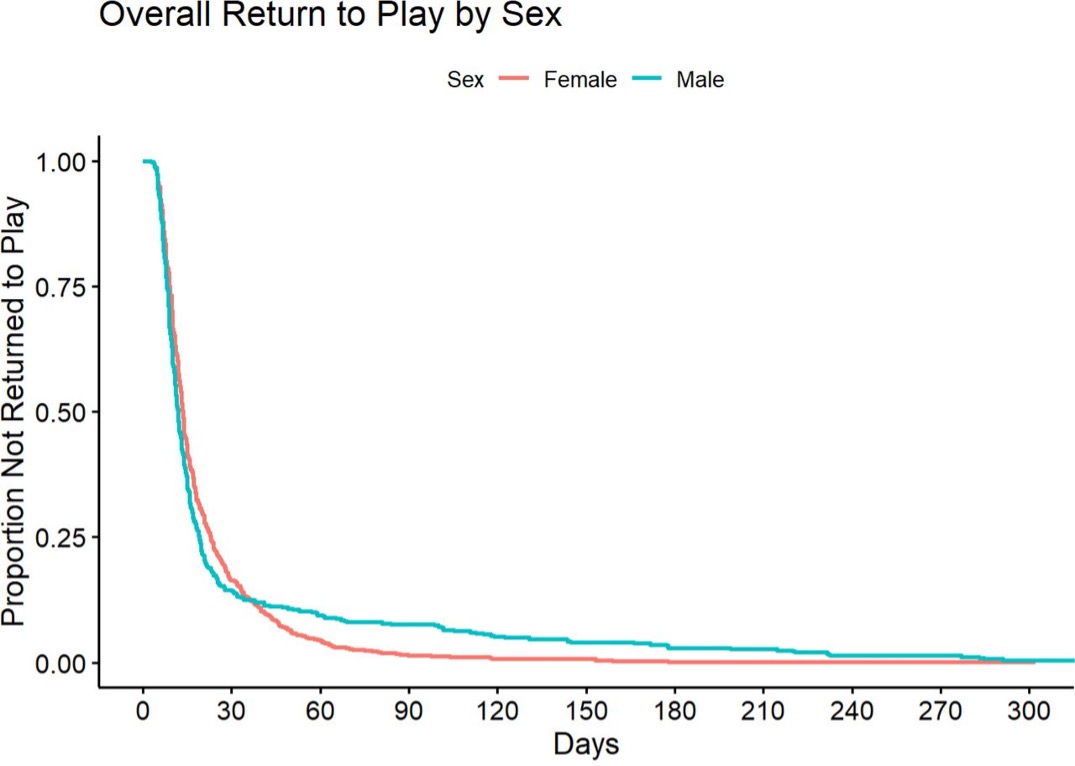

- No difference was found in recovery time to full return to play when comparing female and male concussions.

- When examining subgroups by level of contact, females took longer to recover in contact and noncontact sports, while males took longer to recover in limited contact sports, indicating that recovery is not solely due to biological sex.

- Extrinsic factors, such as Title IX, the historic 1972 US Federal civil rights law prohibiting discrimination based on sex in education programmes receiving US Federal funding, may have had a positive impact resulting in equal access to timely athletic training and sports medical care, which has been shown in other studies to improve outcomes,4,5 effectively closing the gap on any potentially intrinsic, genetically-based disparity in concussion outcomes between the sexes.

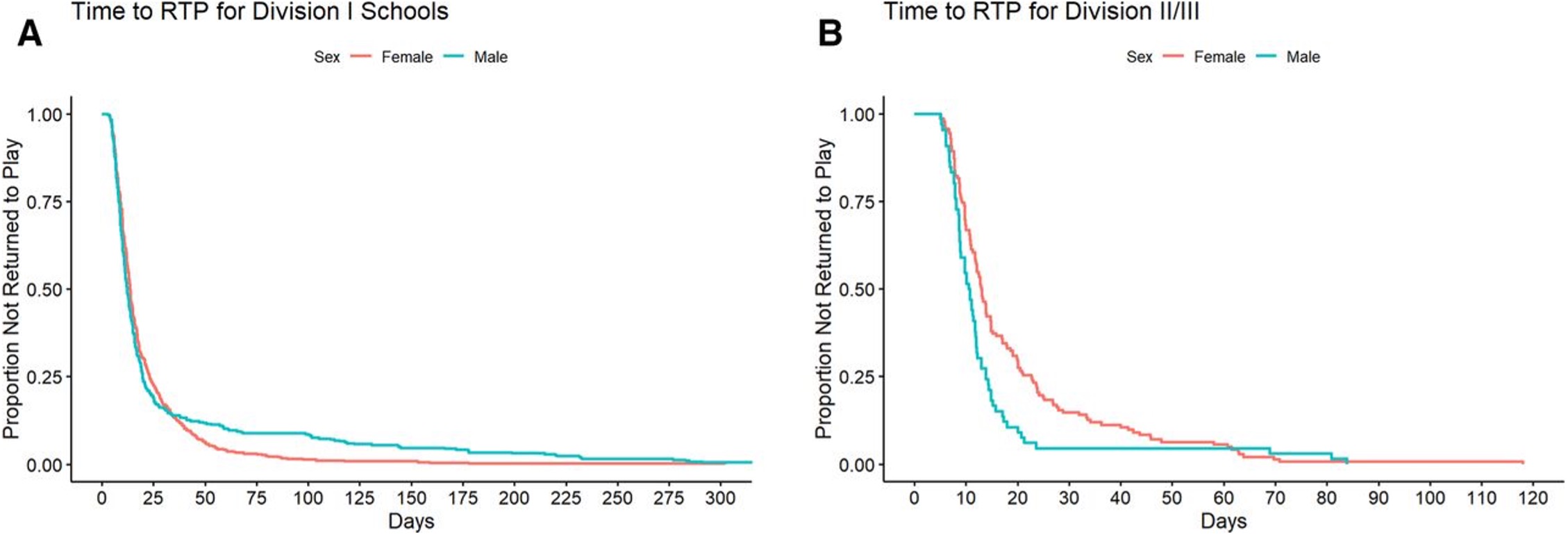

2: Females had longer recovery times at the Division II/III level, but not the Division I level

- When examining concussion recovery times by collegiate Division level of play, we found that females and males recovered at similar time frames at the Division I level, whereas females took longer to recover at the lower Division (II,III) levels.

- Others have reported differences in outcomes for various sports injuries, including concussion, based on Division level of play, related to ratio of athletic training and sports medicine staff to athletes.6-8

- Our findings of longer recovery times in females at lower Division levels of play, may be related to disparities in proportional access to sports medical care after concussion. This might also account for our finding that limited contact men took longer to recover from concussions than their contact male counterparts.

Conclusions

- Despite differences between females and males in risk factors for longer recovery from concussion, such as prior history of migraines or greater symptom burden both before and after injury, overall there were no differences between females and males collegiate athletes in concussion recovery. Genes are not our destiny.

- When comparing by contact level of sports, contact and noncontact females took longer than males to recover from concussion, but limited contact male athletes took longer than females, indicating that biological sex is not the only factor involved.

- There were no differences between females and males in recovery from concussion at the Division I level of play, whereas female athletes took longer to recovery at lower Division levels of play (II/III), indicating that extrinsic factors, such as improving access to athletic training and sports medical care, may improve disparities in concussion recovery outcomes.

Author and Affiliations:

Christina L. Master, MD, FAAP, CAQSM, FACSM

Professor of Clinical Pediatrics

University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine

Co-Director, Minds Matter Concussion Program

Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia

Philadelphia, PA

masterc@chop.edu

Competing interests: None

References:

- Bazarian JJ, Blyth B, Mookerjee S, et al. Sex differences in outcome after mild traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma 2010;27:527–39.

- Covassin T, Swanik CB, Sachs ML. Epidemiological considerations of concussions among intercollegiate athletes. Appl Neuropsychol 2003;10:12–22.

- Broglio SP, McCrea M, McAllister T, et al. A national study on the effects of concussion in collegiate athletes and US military service Academy members: the NCAA- DoD concussion assessment, research and education (care) Consortium structure and methods. Sports Med 2017;47:1437–51.

- Desai N, Wiebe DJ, Corwin DJ, et al. Factors affecting recovery trajectories in pediatric female concussion. Clin J Sport Med 2019;29:361–7.

- Kontos AP, Jorgensen- Wagers K, Trbovich AM, et al. Association of time since injury to the first clinic visit with recovery following concussion. JAMA Neurol 2020;77:435–40.

- Baugh CM, Meehan WP, McGuire TG, et al. Staffing, financial, and administrative oversight models and rates of injury in collegiate athletes. J Athl Train 2020;55:580–6.

- Baugh CM, Kroshus E, Lanser BL, et al. Sports medicine staffing across national collegiate athletic association division I, II, and III schools: evidence for the medical model. J Athl Train 2020.

- Baugh CM, Kerr ZY, Kroshus E, et al. Sports Medicine Staffing Patterns and Incidence of Injury in Collegiate Men’s Ice Hockey. J Athl Train 2020.