By Steffan A Griffin, Amy E Mendham, Peter Krustrup, Andrew Murray, Nick Peirce, Joanne Larkin, Rod Jaques, Charlotte Cowie, Keith A Stokes, Simon PT Kemp

Team sport has been widely hailed as a potential morale-booster for the wider society in the current COVID-19 climate (in both a spectating and participating capacity). However, team sport for most around the world is presently on hold. There is a tangible decrease in physical activity levels across the population(1), and experts predict a profound impact on both physical and mental health as a result of the COVID-19 crisis(2). Team sports increase leisure-time physical activity, and also have psychosocial benefits(3,4). Some patients recovering from COVID-19 require significant rehabilitation, and sport is a great way to help the process(5).

Whilst sporting governing bodies prepare guidelines and policies to comply with social distancing requirements and governmental guidelines, some may feel that such changes threaten the very existence of their sport.

A worrying trend?

At the grassroots level, participation rates of many traditional team sports have been consistently decreasing, especially over the last 5 years (6,7). This contrasts with some data suggesting that physical activity levels actually may be increasing overall across the general population, especially among women and the elderly(6). Are sports losing touch with the general population? Or are they turning to non-traditional sports and individual activities?

Why would people turn away from traditional team sports?

Barriers to participating in sporting activities include: not feeling fit enough to participate; lack of time; poor accessibility, and the cost and fear of injury(8,9). Is it possible to embrace these as challenges and increase the number of people who participate in the general population?

There are ‘bright-spots’ around the world, where these challenges have been met head-on. Both New Zealand Rugby and the Rugby Football Union have announced several significant changes to school and club rugby in an effort to ‘future-proof’ the sport. These include providing flexibility in areas of the game such as team size, game-length, and the degree of contact, with more of a focus on non-contact rugby so players can “enjoy the game without the usual commitment, nor risk of injury”(10,11). In response to concerns around the risks of the developing brain by heading the football, several national football governing bodies have now introduced new guidance around limiting practice of the act for children(12). Walking and mixed-sex versions of multiple team sports (including rugby union and football) now exist to try and overcome some of the aforementioned barriers, and to appeal as sports ‘for life’, similar to the likes of golf and tennis. The Danish Football Association has also introduced recreational football training concepts for untrained women, as well as for patients with prostate cancer and cardiovascular diseases(13).

Paying it forward?

A huge amount of interdisciplinary teamwork has produced COVID-19 sport-specific return-to-training guidelines, demonstrating monumental amounts of flexibility and innovation(14). As such, we know that sports have the ability to adapt (dramatically in certain cases, such as in collision sports), and this could extend to also embrace the important pre-pandemic challenges threatening the future of traditional team sports.

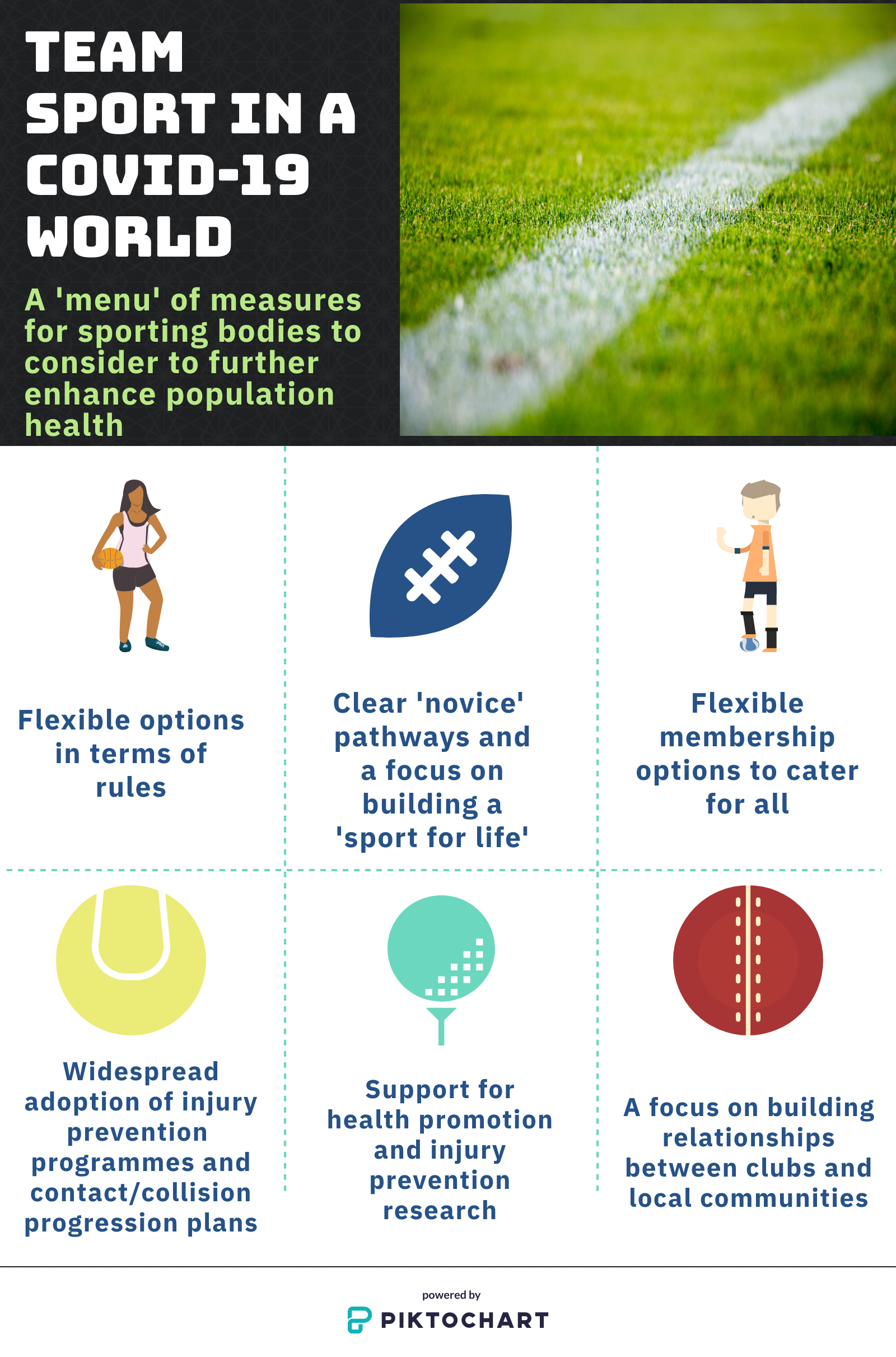

While the impact of any changes on participation are unlikely to be felt (or able to be quantified) for some time, especially given the current landscape, efforts to embrace the views of important stakeholders should be seen as potentially hugely rewarding initiatives. Moving forward, might we see governing bodies focus on overcoming some of the key concerns relating to accessibility, flexibility and risk? Will we see different membership options, activity times, and formats of sports available to the wider population at the ‘coal-face’ of community sport? Will we see a widespread roll-out of evidence-informed injury prevention programmes and more detailed progression plans for contact sports that further embrace the concept of risk-minimisation and health effect-maximisation? Could we see a role for local clubs in the community in encouraging community participation, which could build a wider support-base as a result? All these measures (summarised in Figure 1) might increase the possibility of reaching the World Health Organisation goal to increase physical activity by 15% from 2018 to 2030(15).

Figure one: a ‘menu’ of measures for sporting bodies to consider to further enhance population health.

To quote best-selling author Dave Hollis, “in the rush to return to normal, let’s use this time to consider which parts of normal are worth rushing back to”. The COVID-19 is a crisis that has created challenges that are crushing to certain sports, we should consider the current circumstances as an opportunity to explore new ways to improve health.

***

References

- Comresglobal.com. 2020. Sport England: Survey Into Adult Physical Activity Attitudes And Behaviour « Savanta Comres. [online] Available at: <https://comresglobal.com/polls/sport-england-survey-into-adult-physical-activity-attitudes-and-behaviour/> [Accessed 2 June 2020].

- Holmes EA, O’Connor RC, Perry VH, et al. Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: a call for action for mental health science. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(6):547‐560. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30168-1

- Oja P, Titze S, Kokko S, Kujala UM, Heinonen A, Kelly P, et al. Health benefits of different sport disciplines for adults: systematic review of observational and intervention studies with meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2015;49(7):434-40

- Khan KM, Thompson AM, Blair SN, Sallis JF, Powell KE, Bull FC, et al. Sport and exercise as contributors to the health of nations. The Lancet. 2012;380(9836):59-64

- Barker-Davies RM, O’Sullivan O, Senaratne KPP, et al. The Stanford Hall consensus statement for post-COVID-19 rehabilitation. British Journal of Sports Medicine Published Online First: 31 May 2020. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2020-102596

- Sportengland.org. 2020. Activity Levels At Record High Before Coronavirus Pandemic | Sport England. [online] Available at: <https://www.sportengland.org/activelivesapr20> [Accessed 2 June 2020].

- Statista. 2020. Football Participation England 2016-19 | Statista. [online] Available at: <https://www.statista.com/statistics/934866/football-participation-uk/> [Accessed 2 June 2020].

- Somerset S, Hoare DJ. Barriers to voluntary participation in sport for children: a systematic review. BMC pediatrics. 2018 Dec;18(1):47.

- Gov.Scot. The Scottish Health Survey 2014: Volume 1: Main Report. [online] Available at: <https://www.gov.scot/publications/scottish-health-survey-2014-volume-1-main-report/pages/63/> [Accessed 2 June 2020].

- Immigration New Zealand. 2020. Future-Proofing Our National Game. [online] Available at: <https://www.immigration.govt.nz/about-us/media-centre/newsletters/settlement-actionz/actionz10/future-proofing-our-national-game> [Accessed 2 June 2020].

- England Rugby. 2019. Half Game – Age Hrade Rugby. [online] Available at: https://www.englandrugby.com/participation/coaching/age-grade-rugby/half-game [Accessed 9 June 2020]

- BBC News. 2020. Children To No Longer Head Footballs In Training. [online] Available at: <https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-51614088> [Accessed 2 June 2020].

- Krustrup P, Krustrup BR. Football is medicine: it is time for patients to play! British Journal of Sports Medicine 2018;52:1412-1414.

- BJSM blog – social media’s leading SEM voice. 2020. Working With Government To Plan A ‘Return-To-Sport’ During The COVID-19 Pandemic: The United Kingdom’s Collaborative 5-Stage Model | BJSM Blog – Social Media’s Leading SEM Voice. [online] Available at: <https://blogs.bmj.com/bjsm/2020/05/26/working-with-government-to-plan-a-return-to-sport-during-the-covid-19-pandemic-the-united-kingdoms-collaborative-5-stage-model/> [Accessed 2 June 2020].

- Who.int. 2020. The Global Action Plan On Physical Activity 2018 – 2030. [online] Available at: <https://www.who.int/ncds/prevention/physical-activity/gappa> [Accessed 2 June 2020].

Affiliations/Conflicts of Interest

SG is undertaking a PhD looking into Rugby Union, and Health and Wellbeing at the University of Edinburgh. He also works for the RFU as a Sports Medicine training fellow, and receives financial remuneration for work in professional sport. PK receives financial remuneration for work in professional football, and is a Professor of Sport and Health Sciences at the University of Southern Denmark. AM is the chief medical officer for the European Tour, and receives financial remuneration for work in professional sport. NP is the chief medical officer for the England and Wales Cricket Board. JL is the chief medical officer for the lawn tennis association, and receives financial remuneration for work in professional sport. RJ is the director of medical services for the English Institute of Sport. CC is the head of medicine for the Football Association. KS and SK are both employed by the Rugby Football Union.