By Sean Carmody @seancarmody1

“On every advert you have a bet here and there. You cannot be surprised if people bet. You incite people to bet.” – Arsene Wenger

In March, the sports medicine community traveled to Monaco for their three-yearly pilgrimage.

And the hot topic? Screening in Sport.

Much of the conference debate centred on whether we could screen for (and ultimately, predict) injury in athletes. Largely thanks to Roald Bahr’s keynote (and influential paper here), there was loose consensus that it was not presently possible to accurately screen for future injury, but the screening process was still useful to detect current injury and build rapport with athletes.

Just over a month after the conference closed, the relationship between gambling and professional sport was thrust into the spotlight with the news that Joey Barton had received an 18-month ban for breaking the Football Association’s rules on gambling. Predictably, Barton came out fighting against the ban with a statement which included the following;

“Surely they need to accept there is a huge clash between their rules and the culture that surrounds the modern game, where anyone who watches or follows football on TV or in the stadia is bombarded by marketing, advertising and sponsorship by betting companies, and where much of the coverage now… is intertwined with the broadcasters’ own gambling interests… If the FA is serious about tackling gambling I would urge it to reconsider its own dependence on the gambling industry.”

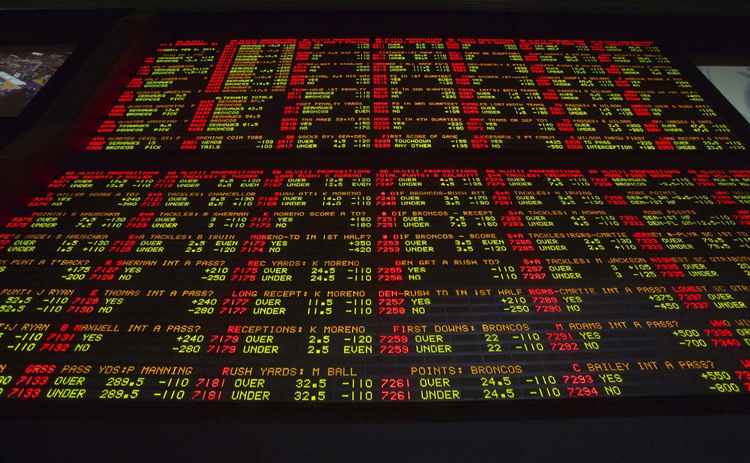

While it doesn’t detract from his offence, Barton has a point. The temptation to gamble is ubiquitous, and few sports are spared from the bombardment. Rugby League, once heralded for their principled rejection of sponsorship money from gambling companies, is now host to competitions such as the BetFred Superleague and the Ladbrokes Challenge Cup. As the late narco-terrorist Pablo Escobar noted; “Everyone has a price, the important thing is to find out what it is”. In this sporting climate, it comes as no surprise that there is a long list of athletes who have succumbed to gambling addiction.

The research on athletes and gambling is relatively limited. However, Michael Calvin (who incidentally co-wrote Joey Barton’s autobiography) sheds further light on the scale of the issue in his excellent new book “No Hunger in Paradise: The Players. The Journey. The Dream”. In interviews with important figures who are combatting the problem, he ascertains that young footballers – specifically targeted due to their premature wealth – are the subject of predatory marketing material by gambling companies. This is concerning considering research which has found that rates of problem gambling are typically highest between the ages of 18 and 24. Calvin also reports that 70% of presentations to the Sporting Chance Clinic relate to gambling addiction. These findings, coupled with the high proportion of athletes who declare bankruptcy soon after retirement (according to a 2009 Sports Illustrated article 78% of NFL players are broke within 2 years of hanging up their cleats), suggests a bleak outlook for the relationship between gambling companies and professional sport.

With this in mind, should we screen our athletes for gambling addiction?

A relatively recent survey carried out in almost 350 footballers and cricketers, found that 6% met the criteria to be classed as ‘problem gamblers’ – more than three times the rate when compared with men in the general population. When you make the rough comparison between that finding and the classical epidemiological studies in football – gambling addiction is nearly as common as quadriceps strains (7%) and much more common than head injuries (2%) (Ekstrand et al., 2011). Perhaps the finding that will make key stakeholders (eg coaches, CEOs) take notice, is the additional evidence that the performance of some players is affected by worries related to their gambling habits, which often take place on the team coach or in hotels, and is (ab)used to soothe their boredom.

In summary, Joey Barton is not the first athlete, and surely won’t be the last, to become a victim of the professional sporting environment which tempts the impulsive to gamble. Further we need more research to better understand the factors which predispose athletes to gambling addiction, and sport-specific screening tools may be required. Moreover, due to its potential to affect performance and result in serious mental health issues, gambling addiction must be considered alongside commonly assessed issues in athletes such as musculoskeletal injury and cardiac screening.

Key Resources:

DSM-5 Diagnostic Criteria for Gambling Disorder.

Sporting Chance Clinic for the treatment of behavioural problems among professional and amateur sports people.

Sean Carmody is a Junior Doctor working in London. He tweets regularly on topics related to sports medicine and performance (@seancarmody1).