#IOCprev2017 Engagement, Evidence & Practice Blog Series

By By Nirmala Perera @Nim_Perera with contributions from @KThorborg and @ryan_timmins

Hamstring injuries

Hamstring injuries are common muscular injuries in athletics1 and in team sports such as football,2, 3 rugby4 and Australian football-5 sports that all involve high-speed running, sudden acceleration and deceleration. These activities increase the eccentric forces within the hamstring muscles, which increases the likelihood for injury.

The long head of biceps femoris (BFIh), one of the four hamstring muscles, is particularly vulnerable to hamstring injury/strain, accounting for 80% of the injuries.6 In sports such as football2 and rugby4, up to 80% of injuries to the BFIh resulted from high-speed running. Greater length changes in BFIh muscle-tendon unit (MTU) at higher sprinting speeds are a likely contributing factor. In addition, age, eccentric hamstring weakness, short BFlh fascicles, increased quadriceps strength (q-strength) and previous injury are also identified risk factors within the sports medicine literature.7

In contrast to the BFIh injuries, the injuries to the medial hamstring muscles are caused by stretching the muscle to the extremes in its range of motion as seen in dancing, gymnastics and tennis for example.8 Reasons for these discrepancies between different types of hamstring injury remains unclear despite growing body of evidence.

The neuromuscular inhibitions post BFIh injury can reduce or hinder the ability to activate the injured muscle effectively, especially during eccentric contractions.9 There are various hypothesized causes for this such as insufficient rehabilitation, impaired nerve conduction and even muscle atrophy. In regards to rehabilitation, some athletes might be cleared to return to play despite the injured/rehabilitated leg still being up to 50% weaker eccentrically than the uninjured leg.10

Hamstring injury prevention strategies

There is promising evidence indicating that the incidence of hamstring injuries can be minimised.11 Nordic eccentric hamstring exercises,11 are effective preventing hamstring injuries. So far, the best available evidence points towards eccentric hamstring strength as the most effective preventive measure in football. For example, when Nordic hamstring exercises were used by male footballers at amateur and professional level, acute hamstring injuries were reduced by 70%.11 The number needed to treat or, in this case, the number of players needed to adhere to the exercise programme to prevent a new, recurrent hamstring injury is 25 and three11 respectively. In addition, the same study reports that new or recurrent hamstring injury can be prevented if 13 players adhere to Nordic hamstring exercises program.11

The best way to prevent hamstring injuries relating to high speed running is by improving capacity. This can be achieved by increasing eccentric strength and tolerance of high running load to high running loads. Improvements in eccentric strength capacity (ECC) are associated with increased ability to dissipate high forces during sprinting. The most potent mechanism of ECC training for injury prevention is that the exercises increase strength; tissue capacity and the length of the BFlh fascicle.

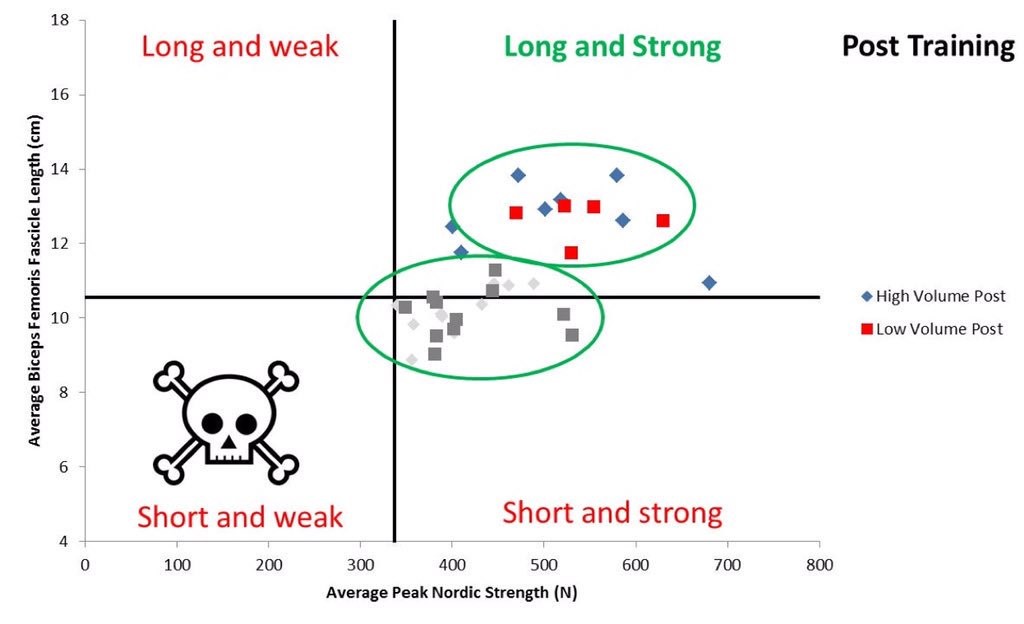

Participants in this study undertook 6 weeks of training with the Nordic Hamstring Exercise at either a high volume (up to 100 repetitions/week) or a low volume (up to 8 repetitions/week). The grey symbols are pre-test measures (fascicle length and eccentric strength), with the brightly coloured ones being post-test. Both groups increased fascicle length and eccentric strength equally. The cut points (black lines) were taken from a prospective injury study within elite Australian football2. Being short and weak resulted in an increased risk of hamstring injury. Therefore being long and strong is important to reduce injury risk.

The frequency at which hamstring injuries occur in both female and young athletes lack the extent of investigation available for male athletes, however, in football, the prevalence is the same across genders.13

In spite of increased knowledge and understanding of hamstring injuries, their management and injury prevention efforts, first time and recurrence of hamstring injuries remains high. A prospective study of elite Danish footballers found that at least three hamstring injuries per team per season were reported.3 On average 22 days were lost from playing football with some players taking up to 136 days to return to sport.

As discussed above, there is strong evidence to support the efficacy of injury prevention programs, however, compliance is low and evidence based injury prevention programs are poorly adopted at elite sporting levels.14 It could be hypothesised that fear, in terms of soreness and the exercise volume could present reasons for low compliance.

Once again, the gap between research and evidence implementation is clearly apparent and efforts need to be continued to find ways to bridge this deficit. As researchers and clinicians we need to work together to bridge this gap. Cutting-edge information on this topic including latest research innovations in implementation will be showcased at the IOC World Conference on Prevention of Injury and Illness in Sport in Monaco (#IOCprev2017). Notably, Kristian Thorborg, Roald Bahr, Rod Whiteley, David Opar, Nicol van Dyk, Anthony Shield and Gustaaf Reurink will share their latest research during Symposium 1 and several practical workshops.

********************

Nirmala Perera (@Nim_Perera) is an epidemiologist and a researcher at the Australian Centre for Research into Injury in Sport and its Prevention (@ACRISPFedUni). She is the @IOCprev2017 #SoMe campaign coordinator.

Ryan Timmins (@ryan_timmins) is a researcher within the QUT-ACU Hamstring Injury Group and a Lecturer at Australia Catholic University.

Kristian Thorborg (@KThorborg) is a physiotherapist and associate professor at Amager-Hvidovre Hospital, in Denmark.

References

- Opar D, Drezner J, Shield A, et al. Acute hamstring strain injury in track‐and‐field athletes: A 3‐year observational study at the Penn Relay Carnival. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2014;24(4):254-259.

- Timmins R, Bourne M, Shield A, Williams M, Lorenzen C, Opar D. Short biceps femoris fascicles and eccentric knee flexor weakness increase the risk of hamstring injury in elite football (soccer): a prospective cohort study. Br J Sports Med. December 16, 2015 2015.

- Petersen J, Thorborg K, Nielsen M, Hölmich P. Acute hamstring injuries in Danish elite football: a 12‐month prospective registration study among 374 players. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2010;20(4):588-592.

- Bourne M, Opar D, Williams M, Shield A. Eccentric knee flexor strength and risk of hamstring injuries in rugby union: A prospective study. Am J Sports Med. September 2, 2015 2015.

- Opar D, Williams M, Timmins R, Hickey J, Duhig S, Shield A. Eccentric hamstring strength and hamstring injury risk in Australian footballers. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2014;46.

- Ekstrand J, Waldén M, Hägglund M. Hamstring injuries have increased by 4% annually in men’s professional football, since 2001: a 13-year longitudinal analysis of the UEFA Elite Club injury study. Br J Sports Med. January 8, 2016 2016.

- Liu H, Garrett W, Moorman C, Yu B. Injury rate, mechanism, and risk factors of hamstring strain injuries in sports: A review of the literature. Journal of Sport and Health Science. 9// 2012;1(2):92-101.

- Askling C, Tengvar M, Saartok T, Thorstensson A. Proximal Hamstring Strains of Stretching Type in Different Sports Injury Situations, Clinical and Magnetic Resonance Imaging Characteristics, and Return to Sport. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36(9):1799-1804.

- Bourne M, Opar D, Williams M, Al Najjar A, Shield A. Muscle activation patterns in the Nordic hamstring exercise: Impact of prior strain injury. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2015.

- Tol J, Hamilton B, Eirale C, Muxart P, Jacobsen P, Whiteley R. At return to play following hamstring injury the majority of professional football players have residual isokinetic deficits. Br J Sports Med. 2014;48(18):1364-1369.

- Petersen J, Thorborg K, Nielsen MB, Budtz-Jørgensen E, Hölmich P. Preventive effect of eccentric training on acute hamstring injuries in men’s soccer. Am J Sports Med. November 1, 2011 2011;39(11):2296-2303.

- Presland J, Timmins R, Opar D. The effect of high or low volume Nordic hamstring exercise training on biceps femoris long head architectural adaptations.; 2016.

- Hägglund M, Waldén M, Ekstrand J. Injuries among male and female elite football players. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2009;19(6):819-827.

- Bahr R, Thorborg K, Ekstrand J. Evidence-based hamstring injury prevention is not adopted by the majority of Champions League or Norwegian Premier League football teams: the Nordic Hamstring survey. Br J Sports Med. May 20, 2015 2015.