Association of Chartered Physiotherapists in Sport and Exercise Medicine blog series @PhysiosinSport

By Tom Goom @TomGoom, Sports Physiotherapist at the Physio Rooms and the creator of Running Physio; lead on Running Repairs Course http://www.running-physio.com/running-repairs-course/

Achilles tendinopathy is a common problem among runners and can be a challenge to manage. As clinicians, we want to help the patient find a balance between the load being applied to the tissue and its capacity to manage this load. This blog is the first in a series that will examine key factors in achieving this balance by assessing and modifying tissue load and increasing load capacity, and offer PRACTICAL applications of knowledge. We are, of course, more than just tissues being loaded and we have to keep the person at the very centre of a biopsychosocial approach. In this case that person will be Al…

Meet Al.

He’ll be joining us as the key figure in a multi-part blog series on managing achilles tendinopathy in runners. Al is a runner with a sore achilles. He will be our case-study to address all aspects of tendinopathy within a biopsychosocial approach. This first blog is about what training errors may have lead to Al’s symptoms. We’d like readers to join in and share their thoughts about it by tweeting @BJSM_BMJ and @physiosinsport using the hashtag #AchillesAl.

A bit more about #AchillesAl

Before we delve in, let’s learn a bit more about Al. Al is 49 year old runner with a 2 month history of right mid-portion achilles pain. He runs an IT company, is married with 2 teenage children and is generally fit and well. His main goal is to complete a marathon in 5 months time in under 3 hours and 30 minutes. His current PB is 3:36 and he’s determined to beat this before he turns 50 next summer!

He reports a gradual onset of achilles pain that began as a niggle then progressed over a couple of weeks to become swollen and painful. It has settled somewhat since, but hurts at the start of a run and then flares-up the following morning if he’s ‘overdone it’. He doesn’t usually get pain with activities of daily living, unless his symptoms have already been aggravated by a run.

Subjective history and objective examination leads to a diagnosis of right mid-portion achilles tendinopathy. Which leads us to an important question:

What factors/conditions have caused this to develop?…

Research suggests 60-70% of running injury occurs as a result of training error. It’s important to identify which training errors may have led to an injury so a runner can learn how to adjust their training to prevent a recurrence. The best way to do this is to get a thorough overview of a runner’s training structure and how it’s changed in the lead up to the injury. Particularly important is to identify relevant change. By this we mean changes to the training that would influence the load on the injured tissue or its capacity to manage that load.

Subjective history is vital in identifying training errors. There’s no recipe to this but it typically involves looking at weekly training structure,examining longer term changes (depending on chronicity of symptoms) and hunting, delving and exploring to see what’s changed!

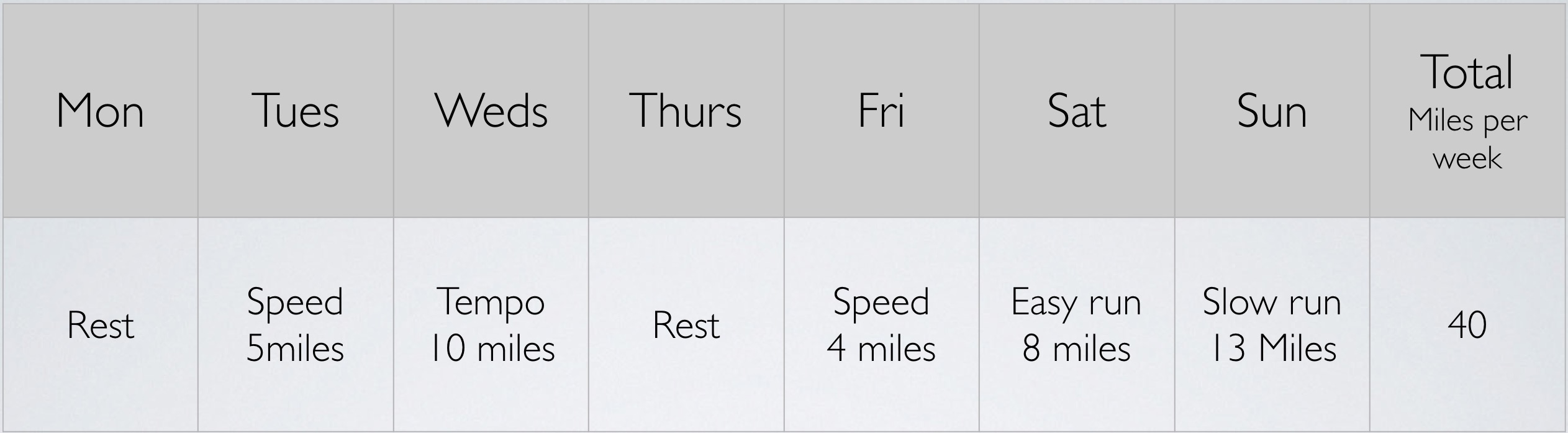

Al’s a very modern runner. At a touch of a button he sends you his typically weekly training schedule;

What are your thoughts? Can you see any training errors that might be relevant?

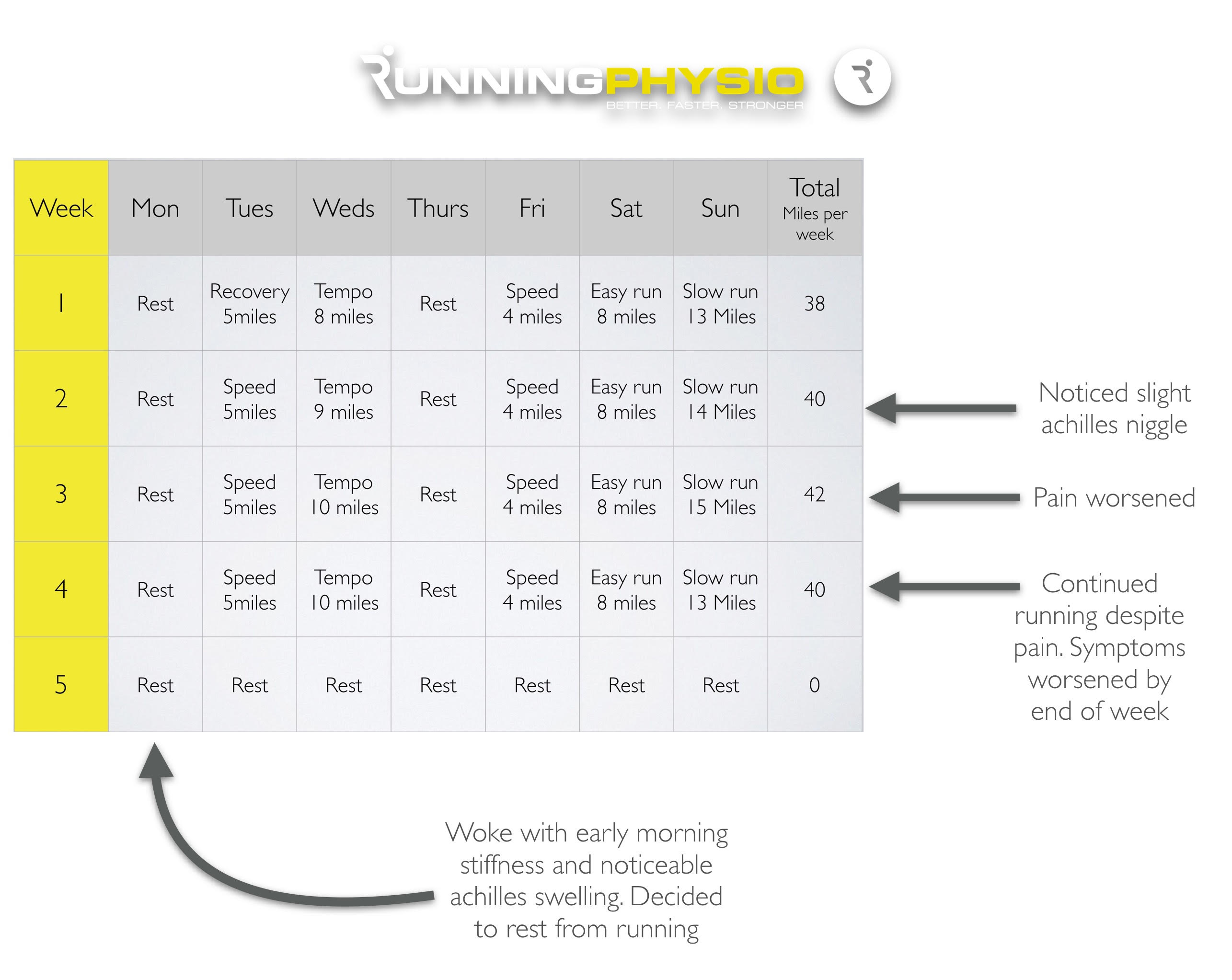

This snapshot it useful but doesn’t tell you the whole picture so Al shares his training schedule in the weeks just prior to the onset of his pain;

What do you think? Any relevant change that might have increased achilles load? Let us know on #AchillesAL.

So we have an overview but there’s still more to know! We need to hunt out those extra, key bits of information. A good subjective isn’t a box ticking exercise to ask pre-determined questions, it’s an exploration of a patient’s personal insights to see where it leads you.

We asked Al, “anything else that’s changed during this time? Did your type of training change, did you change your running surface?”

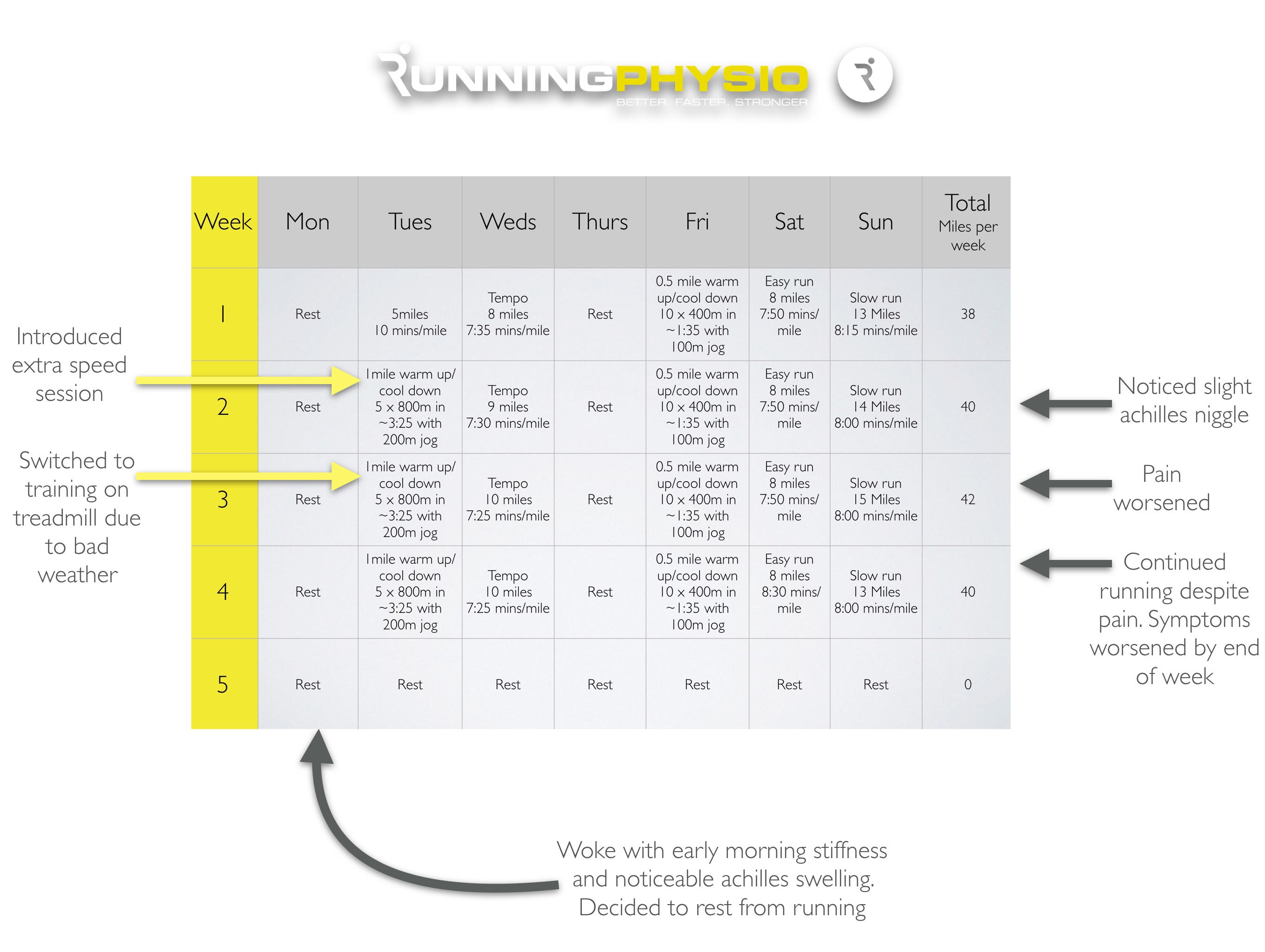

Al replies, “I’ve been pushing a bit harder to improve my pace and I also switched all my training to the treadmill a couple of weeks before it got really sore as the weather was shocking!”

We’re starting to see a couple of reasons how Al’s achilles may have become overloaded and sore but there’s another piece or two left in this puzzle! We know Al’s goal, a sub 3:30 marathon, we can use this to approximate what Al’s running pace should be at each training session. Al may have this information if he’s following a structured plan. However, questioning him further he says his training plan was provided by a friend and doesn’t have those details.

This final step is tricky. For many of us we might need some help approximating training intensity, we might feel it’s outside of our role. In an ideal world we’d work within an integrated, multi-disciplinary team and ask a running coach to help. Sadly for a lot of clinicians we can become quite isolated in clinics and may not have access to this.

**Action point** look to connect with local running coaches in your area to facilitate MDT working

If you feel confident to delve a little further there are some good online resources that can help. The Macmillan Calculator can be a useful tool. If we put Al’s goal time and a recent race time in to the calculator it gives us some approximations of his training paces;

- Speed session: 400 metre intervals ~ 1:34 – 1:39, 800 metre intervals ~ 3:17 – 3:27 (i.e. Run an 800m interval in between 3 mins 17 secs and 3 mins 27 secs)

- Tempo run: 7:21 – 7:37 minutes per mile

- Easy run: 8:10 – 9:11 minutes per mile

- Long slow run: 8:15 – 9:32 minutes per mile

We can then compare that to Al’s schedule;

With all the information to hand, what training errors can you see and how might they affect the achilles?Share your thoughts by tweeting@physiosinsport and @BJSM-BMJ on hashtag #AchillesAl.

Once you’ve given it some consideration scroll down, past the humorous ‘error in loading’ image below to see our conclusions…

Al’s case is interesting because if all you knew was his training basics (e.g. how many times a week he runs, how far and on what days) it’s unlikely we’d identify the key training errors. His training volume (how much he does) is at a normal level for him and only increases very slightly from week to week (approximately 5%). His training frequency (5 sessions per week) remains constant. It’s only when we explore training intensity, pace and type that following the ‘training errors’ appear;

- Training structure – too much speed work

- Long runs are too fast

- Rapid change in training type – addition of treadmill

- ‘Failure to adapt’

Research by Stephen Seiler suggests that endurance athletes should do roughly 80% of their training at low intensity. Indeed even the world’s best distance runners do a lot of slow running in their training. Typically a marathon training schedule for a recreational athlete involves 1 speed session per week. Al has replaced a recovery run with a second speed session and not adapted his other training to accommodate this so his schedule now includes too much high intensity work.

When we examine the pace of each run in detail we see his speed sessions are at about the right pace, e.g. 800 metre intervals in around 3:25 which is well within his target pace of 3:17 to 3:27. His tempo runs are also on target, at around 7:25 to 7:35 minutes per mile. Al’s running a little fast during his easy runs at 7:50 minutes per mile when he should be 8:10 to 9:11.

The biggest issue though appears to be his long, slow run. Al should be doing these slowly according to his plan. His target is 8:15 to 9:32 minutes per mile and typically these runs are around a minute per mile slower than race pace. Al has been doing these at race pace (~8:00 per mile) in an attempt to improve his time. Some coaches recommend doing long runs close to race pace but you need to ensure your body is coping with it and strike the right balance between pushing performance and increasing injury risk. That makes the ‘failure to adapt‘ training error particularly pertinent; if you’re pushing yourself hard you need to monitor how well your body is coping and adapt your training if you start to struggle or you get pain. Al ignored his pain and barely changed his schedule until it reached a point where he couldn’t run.

Thoughts from the MDT

I asked my go to guy for training advice, Exercise Physiologist John Feeney from Pure Sports Performance for his views on Al’s training;

“From a coaching point of view, I don’t think I would ever advocate doing a ‘long run’ at race pace unless it was part of the athlete’s periodised training plan – i.e. a race pace half marathon as part of a marathon training plan. I always have trouble trying to get athletes to slow down during their long, aerobic runs. Its perhaps more a question of educating the athletes about the benefits of the long, slow runs so they don’t take them for granted and appreciate that these should be exactly what they say on the tin…..long and slow!

The need to look at the intensity of training is crucial as this will impact on the overall training load for that session. I have no problem in incorporating 2 HIT sessions for athletes (even novice athletes) in a periodised training plan. Whilst this will lead to short-term fatigue and overreaching, it often results in high levels of adaptation and super-compensation. However, having said that these twice weekly sessions are well controlled, separated by at least 48 hours and form part of a 4-6 week training block, which itself is part of the periodised programme. The overall training load across a week tends to remain the same as other sessions are adapted accordingly.”

How does this influence the achilles?

When identifying training error it’s important to try to reason through how it might influence the load on the injured tissue. Neilsen et al. (2013)reported that injuries to the achilles, calf and plantar fascia are more likely to occur with an increase in training pace (rather than volume). Hamner et al. (2010) found the calf complex to be the greatest contributor to propulsion and load on the gastrocnemius, soleus and achilles tendon increases as we increase running speed (Schache et al. 2014). Some runners will move towards a more forefoot strike as they accelerate (Forrester and Townend 2015) and this has been found to increase achilles load (Almonroeder et al. 2013).

It follows then that the load on Al’s achilles is likely to increase if he increases training intensity. This isn’t necessarily an issue unless the increase is too rapid and excedes Al’s load capacity. Perhaps it might not have done until he added another variable into the mix…

Recent research by Rich Willy et al. (2016) compared overground and treadmill running and found peak achilles tendon force was 12.5% greater on the treadmill. The rapid introduction of treadmill running in addition to increased training intensity may well have tipped the balance and overloaded the tendon.

It’s important to discuss these findings with Al and explain how we think his training may have caused his achilles pain……Al takes on the key messages but, understandably, has some questions…

“What training should I be doing now then?”

“How could I modify it to help my achilles?”

Over to you guys…what do you think? What else might you want to know from Al?

Tweet your answers to @physiosinsport and @BJSM_BMJ on hashtag #AchillesAl and we’ll feature the best suggestions in part 2!…

*********************************************