By David Nunan @DNunan79

Many have commented on the how, who, what and ethical implications following Maria Sharapova’s shock revelation of her failed drugs test. Few have looked in more depth at the why?

Many have commented on the how, who, what and ethical implications following Maria Sharapova’s shock revelation of her failed drugs test. Few have looked in more depth at the why?

The evidence for “why?” in this case falls in to two key areas. First is the evidence that Mildronate (or Meldonium) is indicated for the conditions Maria was taking it for, apparently to “combat a magnesium deficiency, heart problems and because of a family history of diabetes”.

Second, is the question of whether the drug enhances exercise and sporting performance. I will tackle the second issue in my next blog; here I focus on the question:

“What is the evidence for Mildronate/Meldonium to treat heart problems (abnormal ECG), indications for diabetes (familial history) and magnesium deficiency in a 17-year-old athlete?”

Meldonium’s Wikipedia page provides background information on the drug, such as common trade names (“Vazonat”, “Idrinol”, “Msmall”, “Quaterine”, “MET-88”, and “THP”), its chemical name (trimethylhydrasine), one of its Latvian manufacturers, Grindeks, and its widely adopted use throughout Latvia and other Baltic states. It isn’t licensed in the United States or Europe.

A number of clinical trials are cited, unfortunately the links to each of these are dead but they all appear to be conference proceedings.

Grindeks’ own website highlights pre-published results from a 2010 Russian/Latvian/Lithuanian/Ukrainian collaborative phase III RCT. Mildronate proved safe and effective for treatment of angina. The drug’s creator wrote:

“As the author of this medication I have always been sure about the therapeutic effectiveness of Mildronate®…” and “[R]esults of the just-finished multinational clinical trial once more approve effectiveness and the high safety of Mildronate® in the treatment of angina in combination with the standard therapy.”

The webpage does not provide enough detail to ascertain if the study was published in a peer-reviewed journal nor if the protocol was pre-registered.

However, a bit of digging around the website reveals a publication for this study in Seminars in Cardiovascular Medicine.

A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in 371 chronic CHD patients with stable angina aged between 24 and 82 yrs of age (mean ~61 yrs) was performed to assess the effect of 12 months treatment with mildronate on exercise capacity as primary outcome (so not angina onset). In the 278 that completed the study (no details given for drop outs), patients randomized to mildronate improved performance on a cycling ergometer test by an average of 55 seconds.

My comparison of the study against the CONSORT statement suggests several limitations. I couldn’t find methods for (i) the sequence generation of the random numbers needed for randomisation, (ii) allocation concealment or (iii) blinding of investigators. Again, diverging from CONSORT, there is no statistical analysis section. Therefore, I respectfully posit that the findings from this paper would be classed as having risk of bias for internal validity. This would be considered a limitation were a group like the FDA (Federal Drug Agency) asked to approve the drug for clinical practice.

There appears no pre-registered protocol although reporting bias based on methods described in the paper appears low. Adverse effects were not considered as an outcome nor any reported. No information on funding is given and no conflicts of interest are stated. The study lead author and one of its principle investigators are Editors for the journal in which it was published.

But I’ve just committed one of the sins of a none-EBM approach – cherry-picking (2nd definition in link). Perhaps you want a more systematic approach?

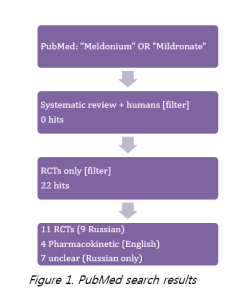

A search of PubMed for “Mildronate” OR “Meldonium” gives 217 returns, 108 of which are in Russian. Filtering for systematic reviews in humans – which would give the highest level of evidence for the efficacy and effectiveness as a treatment for these conditions – gives zero returns.

Filtering for the next level of evidence (RCTs) and only for Mildronate/Meldonium or its drug class gives 22 hits (Figure 1); 11 of which are RCTs (9 in Russian), 4 pharmacokinetic studies (all in English) and 7 studies (all in Russian) where study design/methods are unclear.

Studies were published between 1989 and 2015. The study already looked at in detail on the manufacturer website was not picked up in the search.

First thing of note is that there are a number of RCTs assessing the efficacy of Mildronate/Meldonium but no systematic review.

Ascertaining details from each of the 11 RCTs is limited by language restrictions. It appears the largest included 512 patients and the smallest only 35. Clinical conditions assessed in each trial are listed in Box.

Patient populations included in 11 RCTs of Mildronate/Meldonium

| Coronary heart disease (CHD) [2 studies] |

| Post MI heart failure with [2 studies] or without [1 study] type 2 diabetes (T2DM) |

| Ischaemic stroke [1 study] |

| Post MI [1 study] and after PCI [1 study] |

| CVD [2 studies] |

| T2DM with neuropathy [1 study] |

I note that I cannot read the Russian papers so my comments are restricted to English language papers. It may be that the Russian studies are high quality and cover off the limitations I see in the English language publications. Only one of the English language studies was pre-registered. However, this was done after the trial had started. (On a separate note, I have many reservations about current processes for trial registration — more on this issue here).

None of the English language studies assessed patients with ECG abnormalities specifically (although these will be indicated in a number of the patient groups), nor pre-diabetes or magnesium deficiency, nor in adolescents!

Focusing on English language evidence of the drug for treating ECG abnormalities, the abstract from one study reports a trial of 1000mg/day intravenous Mildronate for 10-14 days in 30 patients aged 45 to 75 years with CHD led to “a decrease in the number of arrhythmia episodes.”

A second English language trial abstract (with only 2 authors) reported that 12 weeks Mildronate (no information on delivery or dose) “decreased the number of epinventricular extrasystoles (p = 0.002) and the number of paroxysmal rhythm disturbances (p = 0.001)” in 67 myocardial infarction survivors aged 40 to 70 years of age.

It’s not possible to assess the risk of bias, the source of funding or conflicts of interest for these English language trials. Neither trial was pre-registered. Taking a leap of faith, let’s assume these trials are at low risk of bias/no conflict of interest etc., they suggest that short-term (intravenous) use of Mildronate may reduce the frequency of ECG abnormalities in people aged 40 to 75 years of age and suffering from CHD or having survived a myocardial infarction.

But these English language studies are too small to be conclusive. A lack of information on delivery mode in one trial impacts on external validity as it is sold to be taken either orally or intravenously.

So what about treating ‘indicators for diabetes’?

Tne trial reports “a statistically significant improvement in renal functioning: GFR [glomerular filtration rate] increased by 20% vs 2% (p < 0.05); proportion of patients with exhausted FRR [function renal reserve] decreased (p < 0.05)” and “A hypoglycemizing ability of Mildronate was noted” in 30 patients aged 43 to 70 with heart failure and T2DM randomised to 1 g/day Mildronate (no information on delivery mode) for 16 weeks.

A second open label trial by the same group found “Mildronate administration improved clinical condition of the study group vs controls by neuropathy and symptoms count scales.” in 70 patients with T2DM & neuropathy randomised to 1 g/day for 12 weeks.

Again, it’s not possible to assess bias and potential conflicts of interest. External validity would appear poor given the patient population and no data on glycaemic control!

Evidence for Mildronate/Meldonium in magnesium deficiency is easy! However, cardiac arrhythmia may be a symptom of a magnesium abnormality (too much or too little) that provides a (albeit poor) mechanistic link for Mildronate/Meldonium use.

Overall, there is some English-language evidence from a few small RCTs that short-term use of Mildronate/Meldomium at 1g/day (intravenously but possibly orally) reduces occurrence of cardiac arrhythmia in high risk (older) patients with CHD. It may also improve renal function in heart failure patients with T2DM and neuropathy symptoms in T2DM.

However, the English-language trials providing this “evidence” are very likely too small and there is high uncertainty about the risk of bias, the quality of the data, conflicts of interest and a lack of data on potential harms.

The question begs “Does the evidence support the decision of the family physician to prescribe Mildronate to a year 17 year old athlete for *treatment* of an abnormal ECG, indicators of diabetes and magnesium deficiency over a 10 year period?”

What would you say if you were on the jury?

In my followup blog (Next week!) I’ll examine whether Mildronate/Meldonium appears to enhance performance.

———————

David Nunan is a Departmental Lecturer and Senior Researcher at the Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences, University of Oxford. He is also a senior tutor at the Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine and a member of the Evidence Live 2016 local organising committee.

Follow @dnunan79