Who are you?

I am Kellie Wilkie, an Australian Physiotherapy Association Titled Sport & Exercise Physiotherapist in Hobart and was the Lead Physiotherapist for Rowing Australia in the Rio Olympic cycle. I travelled with the Australian Rowing Team for 9 consecutive years including being an Australian Olympic Team Physiotherapist for the 2012 London and 2016 Rio games. I am passionate about ensuring that lessons learned in the elite environment can be transferred into preventing injury for developing rowers and athletes. I have recently been involved in the research and publication of several papers in the British Journal of Sports Medicine in relation to Low back pain in sport and rowing.

What clinical tip would you like to share?

Over time, I have learnt that supporting athletes to continue training in the presence of low back pain costs them more modified and lost training days than an immediate unload from aggravating activities with early control of pain. Lost training days is a considerable burden to athlete performance and minimizing this is the ultimate goal.

In research and clinical practice, we cannot agree on what happens to the neuro-muscular system when any one person presents with low back pain. Does the transversus abdominus turn off? Do the gluteal muscles get up regulated or down regulated? Do the erector spinae muscles go into spasm? What is the role of psoas? It is likely that we cannot agree as humans present as individuals and the neuro-muscular changes in the presence of pain are varied.

Clinicians generally do agree that a reduction in pain results in a change in neuro-muscular patterns that are observed in the presence with less muscular splinting and/or inhibition as pain resolves. This is advantageous for the athlete returning to sport where they want to access familial movement patterns to be able to return to their best performance.

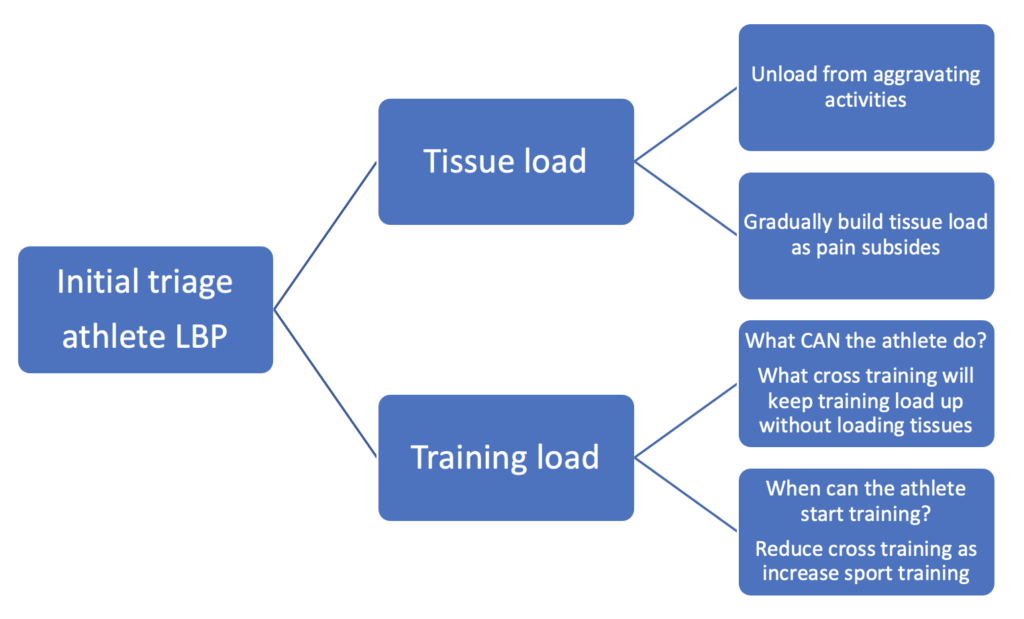

When an athlete presents with low back pain, I immediately start thinking in terms of tissue load and training load.

In the initial triage, I make it very clear that the athlete will be unloaded from all aggravating activities, so their tissues have a chance to recover. In the rowing athletes, this may be the cessation of rowing but may also extend to all sitting. I initially do this for 2-3 days and get the athlete to see a sports physician if my assessment considers that early control of pain would also be enabled by simple pain relief or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medication.

Over the tissue unload period, I prescribe exercise that the athlete can do so that their training load is maintained. For example, the rowing athlete may be able to tolerate sitting on a bike but not sitting and loading in a boat. If sitting is not tolerated, the elliptical trainer or walking up hills may be prescribed. Often, rowers with non-specific low back pain can return to rowing after an initial, early, aggressive unload after a few days.

If the low back pain presentation is more significant, a tissue unload period may be extended, and the training load can then be carefully planned with the athlete and the coach. As pain reduces, tissue load can be re-introduced with specially prescribed exercises and then a trial return to sport. As sport-specific training increases, cross-training with reduced tissue load can concurrently decrease. In my experience, this is the most efficient way to reduce lost or modified training days due to non-specific low back injuries in sport.

Where does this come from?

My time travelling with the Australian Rowing Team allowed me to follow athletes on a daily basis after a presentation of low back pain. Pressure to keep athletes training was always high but this environment allowed very close monitoring to trial different ways of managing acute low back pain presentations. I learnt so much from athlete and coach’s feedback and by attending training and watching athletes attempting to train with pain – where they were not performing at their best. Discussion time with medical team colleagues in an environment that is always trying to minimize lost training time was the ultimate professional development! Athlete and coach expectations were high when important events were close and I learnt to trust myself with aggressive unload and athletes and coaches learnt to trust me as we established relationships over time.

Scientific evidence – if any?

These recommendations come from clinical experience, but they have been explored in a Delphi study of experienced and expert clinicians that I was the lead author for in the British Journal of Sports Medicine in 20201 and the subsequent 2021 consensus statement for preventing and managing low back pain in elite and sub-elite adult rowers2. These recommendations align with recommendations for current best practices in treating low back pain in athletes3, but I do acknowledge that more research is required across sport to understand the best predictive factors for return to sport and performance after a low back pain episode.

References

- Wilkie K, Thornton J, Vinther A, et al. Clinical management of low back pain in elite and sub-elite rowers. A Delphi study of experienced and expert clinicians. British Journal of Sports Medicine 2020 doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2020-102520

- Wilson F, Thornton J, Wilkie K, et al. Consensus statement for preventing and managing low back pain in elite and sub-elite adult rowers. British Journal of Sports Medicine 2020 doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2020-103385

- Thornton J, Caneiro J, Hartvigsen J, et al. Treating low back pain in athletes: A systematic review with meta-analysis. British Journal of Sports Medicine 2020 doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2020-102723