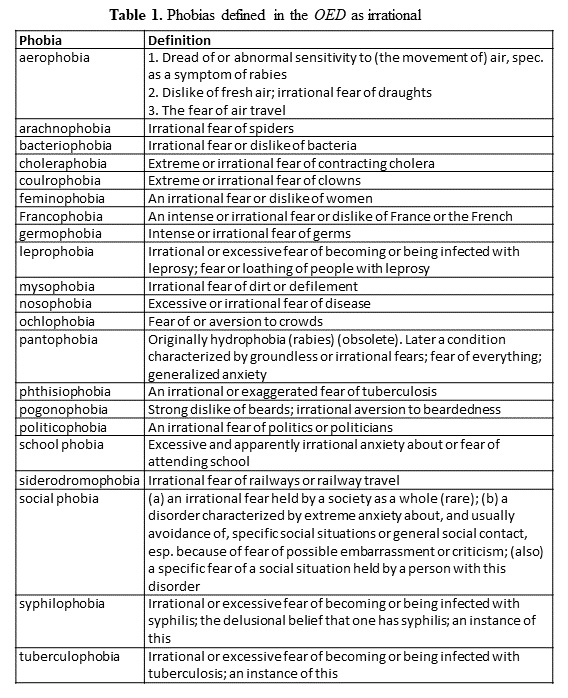

The most unusual entry from among the nearly 600 that were added to the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) in March of this year was coulrophobia, defined in the dictionary as “Extreme or irrational fear of clowns”. However, fears do not have to be irrational. The OED lists over 100 different types of phobias, only 20 of which are defined as being irrational (Table 1); nine of them are about fear of infections.

It’s certainly possible to be justifiably afraid of clowns, conditioned as we have been by the many sinister clowns portrayed in books and the movies. Anyone who has seen It, the movie based on Stephen King’s grotesquely long novel of the same name, and has had nightmares about its eponymous clown-like paedophage, will understand this.

It’s the uncommon conjunction of the l and the r that makes “coulrophobia” seem unusual. The two letters are liquid consonants and are often etymologically interchangeable; consider, for example, milagro, the Spanish word for a miracle, pilgrim, from the Latin word peregrinus, and the pronunciation of the word colonel. However, the –lr– combination is unusual. Other instances include already, chivalry, devilry, revelry, and wassailry, bullroarer, bulrush, malrotation, and railroad, and a few proper names, such as Kilroy, Milroy, Mulready, and Nesselrode. As these examples imply, the conjunction arises only when two different elements are concatenated; no basic IndoEuropean linguistic roots include the combination.

So where does “coulrophobia” come from? Well, the OED frankly admits that it doesn’t know. It floats the suggestion, which it confesses is unlikely, that it’s from a Byzantine Greek word κωλοβαθριστής, a stilt-walker, from Hellenistic Greek, κωλόβαθρον, a stilt, in turn from κῶλον, a limb, + βάθρον, a base or pedestal,.

Might it come from an old French word for a clown, coqueluchier, from classical Latin cucullus, the hood of a cloak? The dictionary doesn’t even consider it. In modern French, incidentally, coqueluche means an infectious disease, typically whooping cough.

A metathetical origin is possible, but none seems likely; colure, for example, “each of two great circles which intersect each other at right angles at the poles, and divide the equinoctial and the ecliptic into four equal parts”, is from κόλουρος, dock-tailed or truncated.

Perhaps “coulrophobia” was just a clownish misprint. Or a clownish invention.

The word “clown” entered the English language in the middle of the 16th century. It came from Scandinavian, Dutch, and German words meaning a block of wood, which gave rise to words such as clod, clog, and clot. In Yiddish a klutz is a fool or a clumsy person. In English, “clown” originally meant a countryman or rustic, implying ignorance or rude manners. Nine clowns appear in Shakespeare’s first folio. They are typically peasants, as in All’s Well That Ends Well, Titus Andronicus, and Measure for Measure. In some cases they are domestic servants, as in Othello and The Winter’s Tale. The clown in Antony and Cleopatra adds tension to the play when, having brought an asp to Cleopatra, he talks to her nonstop, leaving only when she has bid him farewell four times. Some clowns are there for light relief. The two clowns in Hamlet, for example, often reduced in performance to just one, are wisecracking gravediggers. The best known of Shakespeare’s clowns, Feste in Twelfth Night, is called Clown in the stage directions but is addressed by others as “Fool”. His responses are “Better a witty fool than a foolish wit” and “Cucullus non facit monachum [a cowl doesn’t make a monk]; that’s as much to say, as I wear not motley in my brain.” Cucullus again.

By the start of the 17th century “clown” had come to mean a fool or jester on stage or at court or in grand dwellings. A century later it became a character in a pantomime or circus.

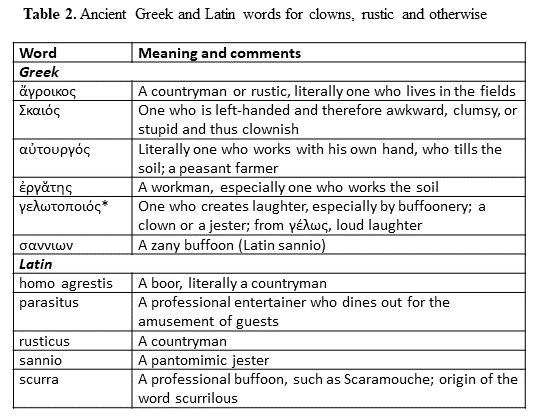

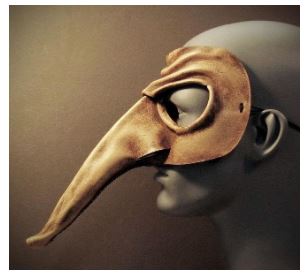

Several ancient Greek words meaning a clown might be added to “phobia” (Table 2). Of these alternatives I prefer σαννιων, reminiscent as it is of “zany”, although the etymologies are different. “Zany” comes from the Italian, zanni or zani, a name given to servants who act as clowns in the Commedia dell’ Arte, including Harlequin, Pulcinella, and Scaramuccia (Figure). “Zanni” is thought to have been a corruption of the name Gianni, and not connected to the Greek or Latin words. So fear of clowns might be called zaniphobia.

A masked Zanni (Wikimedia Creative Commons)

Jeffrey Aronson is a clinical pharmacologist, working in the Centre for Evidence Based Medicine in Oxford’s Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences. He is also president emeritus of the British Pharmacological Society.

Competing interests: None declared.

|

This week’s interesting integer: 287 • Kynea numbers • 287 is the sum of different strings of integers: • 287 is an arithmetic number, because the average of its divisors is an integer: (1 + 7 + 41 + 287)/4 = 84. • 287 is also an RMS (root mean square) number, since the square root of the sum of the squares of its divisors is integral: 12 + 72 + 412 + 2872 = 1 + 49 + 1681 + 82369 = 84100; 84100/4 = 21025 = 1452. 287 is only the fifth such number, the smaller ones being 1, 7, 41, and 239. • 287 is a ludic number (see Interesting integer 277). • Multiply the 7th and 8th primes and then subtract them from the product: • 287 is the 14th pentagonal number. |