| Correction added 24 June 2020: The original hydroxychloroquine plus azithromycin preprint paper mentioned in this article can still be viewed at https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.05.05.20088757v1?versioned=true |

Some articles get retracted. Some get withdrawn. What’s the difference?

As I have previously outlined, “retracted” comes from the Latin verb trahere (past participle tractus), meaning to drag, pull, or draw or carry along in several senses, and by extension to convey an idea mentally. To retract therefore means literally to draw back.

With- as a prefix comes from the Old English preposition wiþ. The þ is an obsolete letter called thorn, which is unvoiced and pronounced like the soft th in thin, in contrast to eth, ð, which is voiced and pronounced like the hard th in that. “Wiþ” meant away or back, as in withhold, to hold back, withstand, to oppose, and withdraw, to leave. These three derivatives are the only ones to have survived the process of obsolescence that many Old English words have undergone. We no longer use, for example withcall, to recall, withdrive, to repel, withleft, abandoned, withscape and withslip, to escape, and withstay, to withstand.

So, etymologically, retract and withdraw mean the same thing, to draw back. But in the world of research publications they have very different meanings and different implications.

Here’s an instance. On 11 May a paper was posted on medRxiv describing an analysis of 132 patients treated with hydroxychloroquine + azithromycin, azithromycin alone, or standard care. On 20 May the paper was withdrawn and the withdrawal statement can be seen on medRxiv: “The authors have withdrawn this manuscript and do not wish it to be cited. Because of controversy about hydroxychloroquine and the retrospective nature of their study, they intend to revise the manuscript after peer review”. As Retraction Watch commented, “It’s unclear why exactly the authors changed their minds about posting the preprint. Hydroxychloroquine was already controversial by May 11 [when they first posted it], and the nature of the study—retrospective—didn’t change in the intervening days.”

This may not seem too serious. In effect, the data have not been published and may never be. All that is left is the original protocol on ClinicalTrials.gov. But the experiences of 132 patients, who gave their informed consent and presumably expected to make a positive contribution to clinical progress by participating, have been squandered. Furthermore, those who had nine days during which to formulate a view, before the medRxiv preprint was withdrawn, may have been influenced by it and may have started using the combination of hydroxychloroquine plus azithromycin, perhaps to the detriment of some of their patients, from the risk of QT interval prolongation and torsades de pointes.

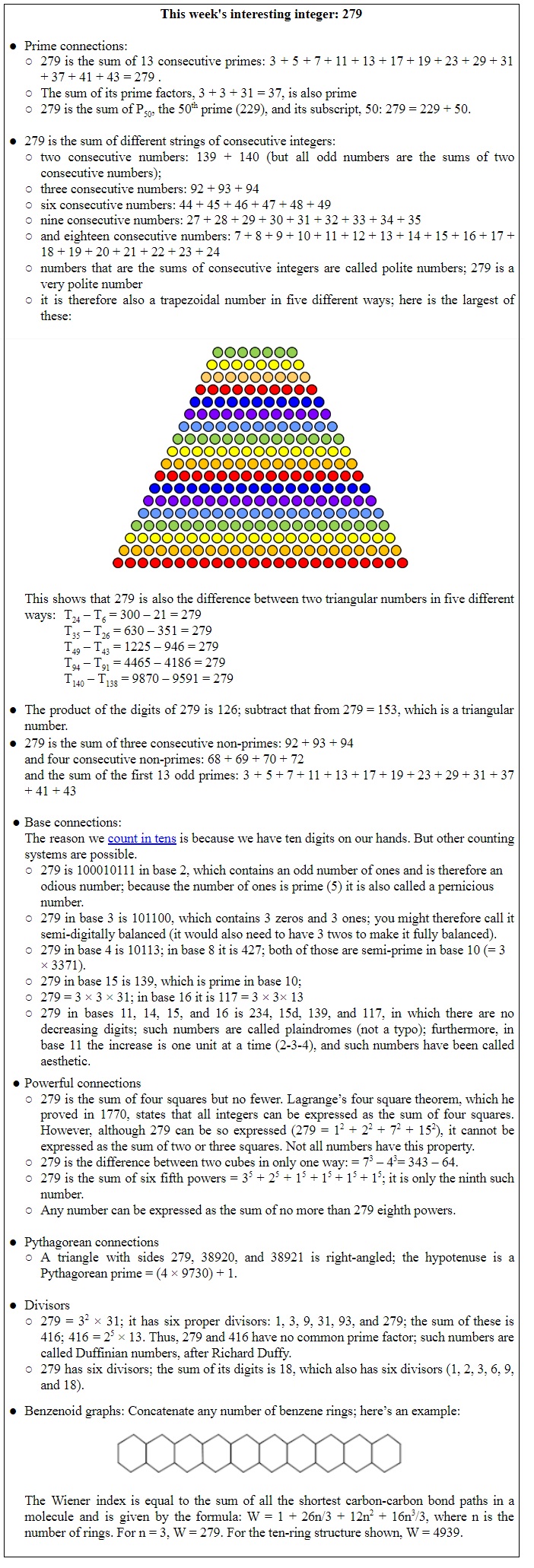

Here’s another example. Last week I mentioned a study of the use of ivermectin that was published on 21 April and described as an “observational propensity-matched case-controlled study in 1408 patients”; 704 received ivermectin and 704 did not. Ivermectin was associated with lower in-hospital mortality: 1.4% versus 8.5% (HR = 0.20; 95% CI = 0.11-0.37: P<0.0001). These striking results were mostly enthusiastically received (Box 1), although some queried their provenance. But then the preprint was withdrawn without stated reasons. One of the authors later told Nature that the preprint was “not ready for peer review”.

Box 1. A selection of comments from reddit.com (all direct quotes) about the now withdrawn ivermectin study

So again, what’s the problem? In effect, the data have not been published. But this time we have evidence that others have picked up the idea and run with it. As was reported on 9 May in the Peruvian journal Ciencia y Tecnología para el Desarrollo (Science and Technology for Development), ivermectin has been approved in Peru for treating covid-19. Since then another preprint has appeared in medRxiv, posted on 10 June, reporting the results of a retrospective cohort study of 280 patients, in whom ivermectin reduced mortality from 25% to 15% (OR = 0.52; 95% CI = 0.29-0.96; P=0.03). Cue more excited comments on Twitter.

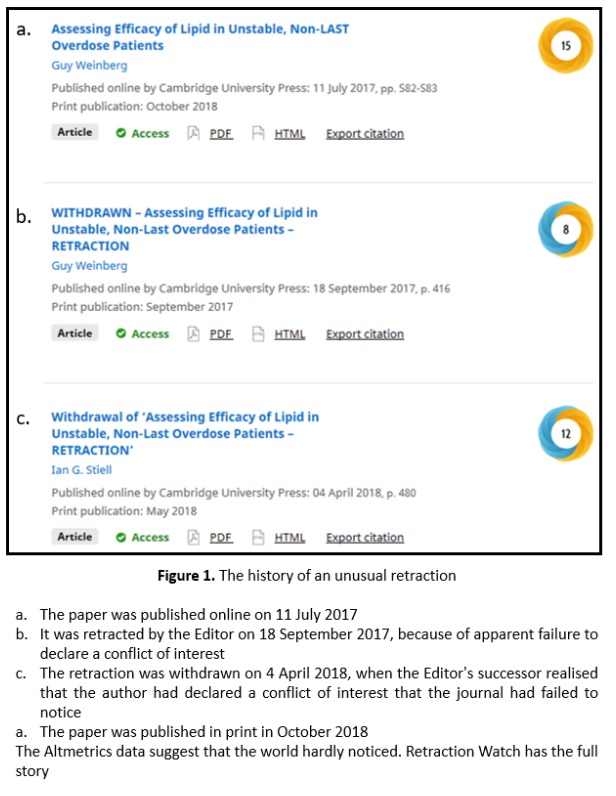

Of 26 studies listed on ClinicalTrials.gov, about a handful look as if they may be double-masked randomized placebo-controlled trials of ivermectin. While we await the results, here’s an unusual case of withdrawal of a retraction (Figure 1).

Retracted papers are potentially damaging, but they remain in the public domain. They can be scrutinized and the reasons for retraction examined. The two examples I mentioned last week illustrate this. Withdrawn papers disappear, having potentially done their damage.

Jeffrey Aronson is a clinical pharmacologist, working in the Centre for Evidence Based Medicine in Oxford’s Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences. He is also president emeritus of the British Pharmacological Society.

Competing interests: None declared.