2020 is Florence Nightingale’s bicentennial year, designated by World Health Organisation (WHO) as the first ever global Year of the Nurse and Midwife. Announced early last year, WHO can have had little idea how 2020 would start for the world’s nurses. Welcoming the announcement at the time, the comments of Donna Kinnear, CEO of the UK’s Royal College of Nursing, were prescient: “If we are to address global health inequality and combat major disease in this century, shortages [of nurses] is something that must change.”

As covid-19 sweeps across the world, the skills of nurses are shown to the world as rarely before. Two years earlier, Nursing Now, a campaign of the Burdett Trust for Nursing, the International Council of Nurses (ICN) and WHO, was launched to raise the profile of a profession too little recognised or valued.

2020 was the year when plans were already in hand to celebrate the 200 year anniversary of the birth of Florence Nightingale, widely regarded as the founder of modern nursing.

Recently, the UK’s prime minister, Boris Johnson, was seriously affected by covid-19 and admitted to London’s St Thomas’s Hospital, where Florence Nightingale’s first school for training nurses was established in 1860. In his first speech after his return to work, Johnson said: “my nursing care has been astonishing.” As he thanked a long list of nurses, he singled out Jenny from New Zealand & Luis from Portugal who, he said, “stood by my bedside every second of the night; watching, thinking, caring.” The challenge for nurses is that good nursing is not visible in the way dramatic surgery, new drugs, or technical innovations are. To some extent it has to be experienced.

The world’s nurses have come forward to care for the thousands of people stricken with this virus and already we are seeing health service staff paying with their lives. ICN believes that at least 90,000 healthcare workers have been infected, and more than 260 nurses have died. Florence Nightingale made it clear on a number of occasions that she would hold back “her” nurses if the conditions weren’t right and too many nurses, in rich countries and poor, are required to work without adequate protection.

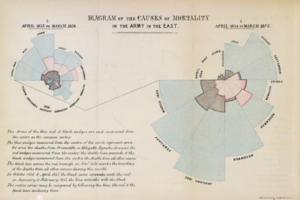

However, Florence Nightingale did not just reform nursing, she had two other skills that would be so useful in this pandemic. Her mathematical genius was what really saved many lives. As the world today struggles to make sense of algorithms, graphs and charts, she was a true pioneer in the graphical representation of statistics, developing a type of pie chart which became known as the Nightingale rose diagram (see figure) which she used to present reports on the nature and magnitude of conditions in the Crimean War to MPs and civil servants. Rather than lists or tables, she represented the death toll in a revolutionary way. Her ‘rose diagram’ showed a sharp decrease in fatalities following the work of the Sanitary Commission – it fell by 99% in a single year. The diagram was so easy to understand it was widely republished and the public understood the urgent need for change.

Her work meant new army medical, sanitary science and statistics departments were established to improve healthcare. She was the first woman elected to be a member of the Royal Statistical Society and later became an honorary member of the American Statistical Association.

Florence Nightingale implemented hand washing in British army hospitals. First publicised by Hungarian doctor Ignaz Semmelweis in the 1840s, who had observed the dramatic difference it made to death rates on maternity wards but failed to persuade his medical colleagues, Florence Nightingale implemented handwashing and other hygiene practices in the war hospital in Scutari and her handwashing practices achieved a reduction in infections.

Nightingale’s attention to international medical research and developments was just one other factor behind her ability to make effective interventions in public health.

At C3 we have been working with nurses to better understand the risks of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) for themselves, their families and their patients, but we didn’t realise they would be so significant in those badly affected by the coronavirus. Obesity, hypertension and diabetes are present in the people requiring critical care in many countries. That poverty and social deprivation should be significant will not surprise the nurses who see the disproportionate burden of NCDs born by the less well off.

Florence Nightingale would have brought the facts clearly presented to campaign against these injustices so that we learn from these difficult times to build a healthier world.

On May 12th 2020, International Nurses’ Day and the 200th anniversary of Florence Nightingale’s birth, we thank our nursing colleagues and hope they stay safe and strong.

Christine Hancock was General secretary, Royal College of Nursing, 1989-2001, and President of International Council of Nurses, 2001-2005. She founded C3 Collaborating for Health in 2009.

Competing interests: None declared