Last week, I reported my analysis of over 800 reports of drug shortages, published since the first report of shortages of quinine and mepacrine in India in 1942.

In surveying the literature, I was struck by how infrequently clinical harms attributed to drug shortages had been reported until relatively recently. In illustration of this, consider three papers, published by the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists.

- The first, “ASHP Guidelines on Managing Drug Product Shortages” (2001), discussed the causes of shortages under 11 headings and actions that might be taken under 13 headings.

- The second, “ASHP Guidelines on Managing Drug Product Shortages in Hospitals and Health Systems” (2009), introduced only minor changes and added a diagram detailing processes for decision-making in the management of shortages.

- In the third, “ASHP Guidelines on Managing Drug Product Shortages” (2018), there were more major headline changes, and this time a completely new section, titled “Patient safety”, with references from 2010 onwards.

I have now reviewed again the papers that I originally found in my search for drug shortages, this time looking for harms, and again relying on the titles and MeSH terms listed in PubMed. Although I restricted my survey to papers published since the year 2000, the total corpus included 761 papers out of the original 811 published since 1942, with additional references from the papers I found, emphasizing again that this is a relatively recent problem.

As well as frustration and anxieties, drug shortages can cause four types of clinical harm:

- failure to treat conditions properly, with delays and suboptimal treatment or none;

- withdrawal effects (e.g. during shortage of heroin);

- adverse effects of substitute medications;

- medication errors, particularly when the substitutes are unfamiliar.

In addition, extra monitoring and referrals to other facilities may be required, clinical trials may be disrupted because of reduced recruitment, and drug expenditure may increase.

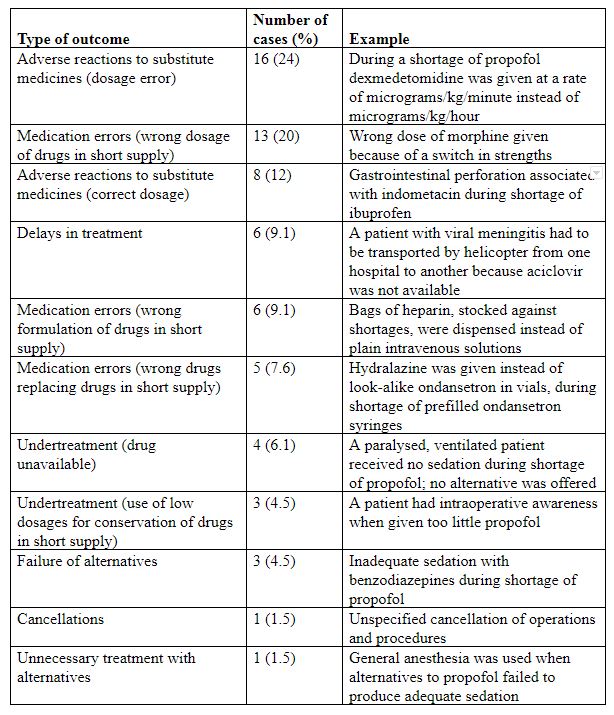

In some cases authors have reported observing few if any harms as a result of shortages. However, harms do occur, as the examples in Table 1 show.

Table 1. A summary of 66 unwanted outcomes selectively reported from a database of over 1000 cases reported to the Institute for Safe Medication Practices in 2010

How often do we discover that treatments we thought would be effective are not, or may even be harmful? 1007 patients, who were given antivenom after being bitten by snakes, underwent a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of subcutaneous adrenaline, intravenous promethazine, and intravenous hydrocortisone, each alone and in all possible combinations, in the hope of preventing adverse reactions to the antivenom; 752 (75%) had acute reactions to the antivenom (9% mild, 48% moderate, and 43% severe); adrenaline significantly reduced severe reactions to antivenom by 43% (95% CI = 25, 67) at 1 h and by 38% (95% CI = 26, 49) up to 48 h after antivenom administration; hydrocortisone and promethazine did not, but adding hydrocortisone negated the benefit of adrenaline.

So it may be no surprise that drug shortages may in some cases prove beneficial, when ineffective or harmful treatments are withheld. For example, during a shortage of noradrenaline 214 patients with severe sepsis or septic shock were either given noradrenaline (n=106) or not (n=108). A retrospective analysis showed that there was no difference in ICU length of stay after controlling for differences in intensity of the illness (APACHE II score), age, weight, and sex; however, those who were not given noradrenaline were more likely to survive (OR = 5.9; 95% CI = 3.1, 11). But perhaps the difference was accounted for by the higher serum lactate concentrations in the treated group, which were not controlled for. In another study of septic shock noradrenaline shortage was associated with increased mortality.

Publication bias takes two forms. In the better known form, studies of interventions that show no benefit are not published. In the less well known form, studies that show harms are not published either. Together, these two forms of publication bias lead to overestimation of benefits and underestimation of harms. I suspect that both forms of bias have affected studies of drug shortages, perhaps tilting the balance in the opposite direction.

Jeffrey Aronson is a clinical pharmacologist, working in the Centre for Evidence Based Medicine in Oxford’s Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences. He is also president emeritus of the British Pharmacological Society.

Competing interests: None declared.