The NHS’s position as the sole employer of trainee doctors is pushing down working conditions, says Jacob Wilson

Around the time the Soviet Union collapsed, a Russian bureaucrat asked the economist Paul Seabright who was in charge of the bread supply to London. Seabright retorted “nobody” to the rather shocked Russian official. The fact that London was adequately supplied by bread was due to the “invisible hand of the market,” to quote the 18th century economist Adam Smith, and was not controlled by any body of centralised planners.

Around the time the Soviet Union collapsed, a Russian bureaucrat asked the economist Paul Seabright who was in charge of the bread supply to London. Seabright retorted “nobody” to the rather shocked Russian official. The fact that London was adequately supplied by bread was due to the “invisible hand of the market,” to quote the 18th century economist Adam Smith, and was not controlled by any body of centralised planners.

If, however, the bureaucrat had asked today “who is in charge of the supply of trainee doctors,” Paul Seabright may have easily answered “Health Education England.”

Compared to other UK professions, the labour market for doctors in training is unusual. The NHS and by default the government operates as a monopsony. This is a technical term to describe a market in which there is a significant or sole purchaser of goods or labour. This unique position significantly alters the balance of power between the purchaser of labour (the NHS) and the labour force (doctors), which I’d argue can be seen in the employment conditions for junior doctors.

The bargaining power of the monopsony is huge given that it’s the sole employer of trainee doctors, meaning it can negotiate, or force through, stagnating salaries. Indeed, the BMA has worked out that there’s been up to a 30% pay cut in real terms for doctors over the past decade.

In addition to wages, monopsonies can also force poorer working conditions upon the labour workforce compared to a competitive market. This can manifest in worsening shift patterns, difficulties in accessing leave, and less say over where one works geographically. A dossier of the poor treatment NHS trainees have received was recently released, which highlighted all of these problems as prevalent experiences in the NHS.

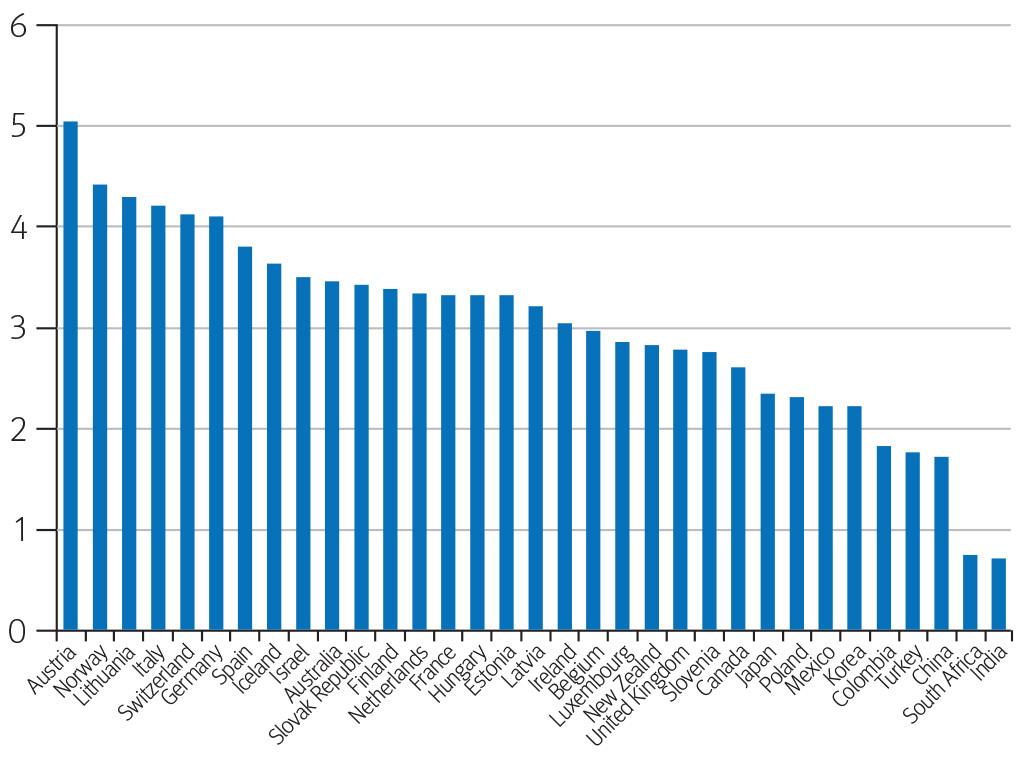

Monopsonies also tend to employ fewer people than there would normally be in a competitive labour market. This is illustrated in the NHS by the fewer number of doctors the UK has per person compared with most other countries in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), which tend to have a lesser degree of centralised oversight.

This brings me back to the role of Health Education England (HEE), whose mission includes “ensuring that the workforce of today and tomorrow has the right numbers.” This ultimately translates to them deciding the number of training jobs for doctors in the UK and where they’re located.

Yet as we’ve so often seen, the centralised allocation of training jobs to different departments and hospitals is not always enough to supply the healthcare demands placed on the hospital. The hospital, which has a much better idea of its own staffing needs, must then try and recruit non-training doctors in order to plug these gaps. However, since they’re non-training jobs, they’re often mainly for service provision and not as attractive. This, combined with the fact that departments have minimal wiggle room for offering other incentives (mainly an increase in pay), means that the problem of rota gaps is difficult for hospitals to solve individually. Ironically, they will often end up having to offer the same shift on a locum basis—last minute and at a much higher rate.

Between 2014 and 2016, there was a 17% rise in the number of doctors registered to work in Australia (from 4182 to 4881) and New Zealand (from 424 to 497). While we don’t know how many of these doctors actually left the UK, I think that greater freedom to choose where to work, better pay, and better conditions should be considered major factors in UK doctors’ interest in working abroad. I know that these factors were all considerations in my decision to work abroad for six months in New Zealand. Similarly, only 37.7% of foundation year 2 doctors progressed straight into specialty training in 2018, another year on year decrease, and a trend which has been ongoing since the survey began in 2011. While data suggest that most trainees who don’t go straight into specialty training do eventually return to the training pathway in the NHS, I think that both these trends can still be partially explained by the working environment.

The application of simple economic principles to the problems we have with doctors’ staffing and their working conditions can give us a framework from which we can begin to try and understand the causes and attempt to offer solutions. In this case, it would appear to me that the unique position the NHS holds as being the sole employer of trainee doctors, facilitated by HEE, may play a part. Decentralising the system by giving individual trusts more responsibilities over hiring trainee doctors may help to address the power imbalance between employer and employees.

Jacob Wilson is a surgical trainee in the South West. He has an interest in economics and its application to contemporary issues.

Competing interests: None declared