The phrase research active is being used more and more in the description of health and social care providers, yet we haven’t clarified what this means to people (patients) using those services.

The phrase research active is being used more and more in the description of health and social care providers, yet we haven’t clarified what this means to people (patients) using those services.

The general definition of the term research active is most often applied to an individual who conducts research on an ongoing basis and ensures it is a significant focus of their academic activity. This describes the researcher and their gain, but what should research active mean when applied to a hospital, for general practice, or in a care home? Does it actually matter and what benefits might there be for patients?

I was asked recently if all this emphasis on being research active was taking the focus away from basic care and treatment. It was an illuminating question which challenged the way we blandly use terms that become a familiar shorthand within a community. It highlights a viewpoint that research can be seen as an added extra rather than an essential ingredient of the best care. It concerns me that talk of research active hospitals might be perceived as taking away from good care.

I have a professional interest through work, but it is also driven by my own health experience many years ago. I was receiving care for throat cancer. By chance I was seen by two consultants who happened to be active in research at a national level. I didn’t know this fact for many years. They explained that the best evidence was for a voice box removal, but based on their clinical experiences and my tumour, they recommended radiotherapy.

It struck me that their decision was based on understanding research knowledge, their clinical experience and observation of the patient’s needs. These critical factors are more than just providing the best evidence based care. They involved a full and frank discussion between us in the days before talk of shared decision making.

The meaning of research active has therefore got to be more than the “best” treatment, being a researcher, promoting research, or giving more people access to well designed studies delivered to time and target. These may be essential ingredients and measure milestones on the journey, but they are not destinations.

Being research active, in my opinion, is fundamentally about our willingness and diligence, as patients, to ask questions and seek high quality evidence either as a patient, a health professional, and from an organisational standpoint.

As patients we need to ask for the evidence. We should be able to read about the findings in plain English. We must be part of a meaningful and informed conversation. We should have guidance on the questions to ask about whether to take part in research. We must be kept informed about the progress of individual studies. We should be able to find out how to get involved with researchers to inform, shape, and influence all aspects of the process. A research active patient might be described as purposely enquiring about evidence to support their own health.

For health professionals it may be about asking how research can assist in all stages of the patient pathway. It is where research moves from being a last option to a helpful guide. We only need look at the transformations in the outcomes of young people with rare diseases or in many cancers where research is a frontline treatment. A research active health professional might then mean being fully engaged with research as a means of benefiting patients through networking with colleagues and the public.

In health and care settings, hospitals, clinics, general practice, and care homes, the value and benefits to local people of research should be clearly on display for all to see. Outpatient letters and other communications should make opportunities to participate clear as well as reminding people of their rights. A research active organisation might be defined as forthright in explaining the purpose of carrying out research together with the patients, public, and partners.

There is also a need to ask questions about the way research is done and how it should adapt to the greater use of mobile health, digital technologies, and big data. We are already seeing more adaptive research with Studies Within A Trial (SWAT). Research active practice might be a phrase applied to the way researchers carry out their work and make it easier for the public to participate.

So, as I return to the question I was asked about whether research takes away from good clinical care. I believe that being research active adds value, but like the questioner I too want the focus to be on good clinical care. I want a good clinical experience based on the rigour of high quality research methods to validate the evidence to improve health and wellbeing. I want a good hospital that is active in research not a “research hospital.”

As I reflect on my own treatment—research was not an answer, it was more accurately the means of asking questions about what was best for the patient. Ultimately, it seemed to be more about a genuine conversation in which research was fully discussed as part of shared making. If we accept that research active is about enquiry then it must be done with those who use the services and the community.

Derek Stewart is a patient advocate who is passionate about the importance and value of research. He is currently the associate director for Patient & Public Involvement & Engagement with the National Institute for Health Research and supporting the work of Nottingham Biomedical Research Centre. A former teacher, Derek was treated for throat cancer in 1995.

My Twitter handle is @DerekCStewart

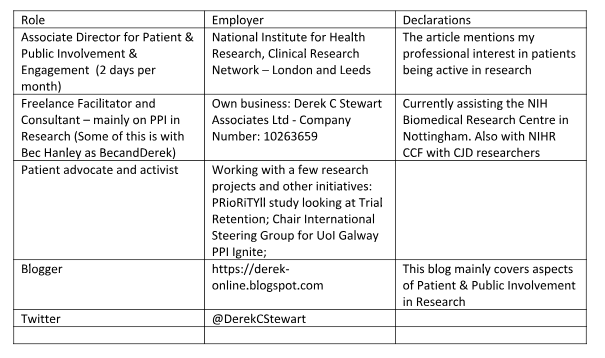

Competing interests: