As I discussed last week, the physicist Alan Sokal has pointed out that “ . . . well tested theories in the mature sciences are supported in general by a powerful web of interlocking evidence coming from a variety of sources; . . . the progress of science tends to link these theories into a unified framework, so that for instance biology has to be compatible with chemistry and chemistry with physics.” This interconnectedness is fundamental.

As I discussed last week, the physicist Alan Sokal has pointed out that “ . . . well tested theories in the mature sciences are supported in general by a powerful web of interlocking evidence coming from a variety of sources; . . . the progress of science tends to link these theories into a unified framework, so that for instance biology has to be compatible with chemistry and chemistry with physics.” This interconnectedness is fundamental.

At the etymological core of “interconnectedness” is the IndoEuropean root NED, to bind or tie. The Latin derivative, nexus, meant a bond or tie of any sort, such as a legal obligation, a clasp or embrace, and by extension the coils of a snake or a knotty problem. The corresponding verb, nectere (supine nexum), meant to bind or tie, to plait or interweave, to string together, to prepare a trap, or to compose poetry, stories, or speeches. “Nexus” was imported unchanged into English in the mid 17th century, the earliest recorded use, according to the OED, being in Some Considerations Touching the Usefulness of Experimental Natural Philosophy by Robert Boyle (1663), who used it to mean the junction between two bodies. Boyle described how what he called “invisible corpuscles” from certain objects worn externally, such as amulets, could cure or prevent certain diseases such as epilepsy (“the falling sickness”), quoting Galen in support. “That such invisible bodies,” wrote Boyle, “by passing through grosser ones, and thereby changing the motion and nexus or juncture of their parts, may produce lasting alterations in the textures (though it be a paradox) seems not at all to me impossible.”

In grammar a nexus, a term introduced by the Danish grammarian Otto Jespersen in 1917, is a group of words (with or without a verb) expressing a predicative relation. In The Philosophy of Grammar (1924), Jespersen gave an example: in the sentence “the dog barks”, “barks” is a nexus, annexed, as it were, as a predicate of the subject “the dog”, whereas in the phrase “the barking dog”, “barking” is joined to the subject, a construction that Jespersen called junction. Jespersen identified several different forms of nexus, including those involving finite verbs (“the rose is red”), infinitives (“I heard her sing”), adjectives (“I found the cage empty”), and forms called nexus subjunct (“weather permitting”) and nexus deprecation (“heaven forbid!”).

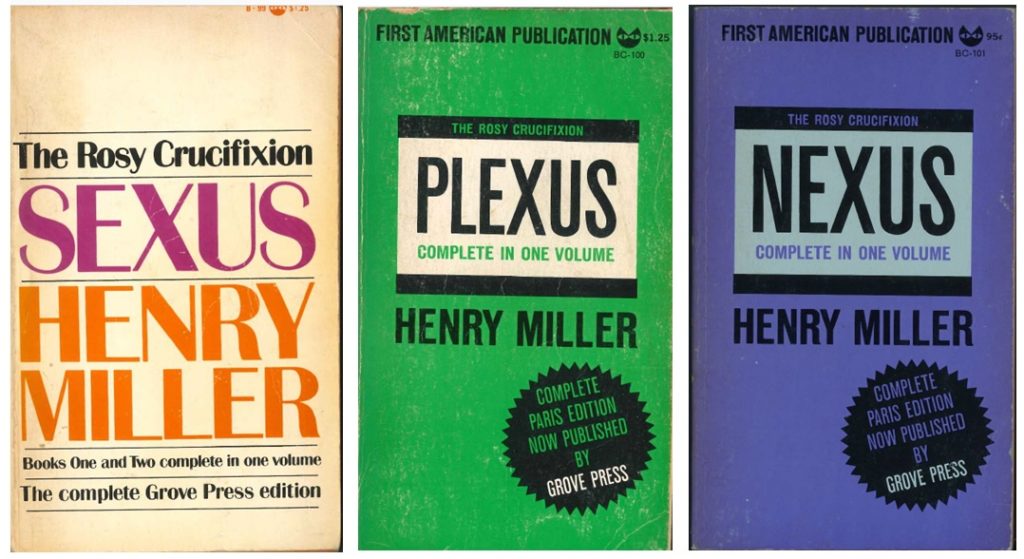

A nexus can also be a connected group, series, or network, a point of focus, and in cell biology “an area of fusion or close contact between two adjacent cell membranes, which is characterized by low electrochemical resistance” (OED), although my impression, looking at the scientific literature, is that it is often used loosely simply to mean any connection. Henry Miller completed the interconnected volumes of his Rosy Crucifixion trilogy with Nexus, which also rhymed with the titles of the previous two volumes, Sexus and Plexus (pictures).

Nexus also gives us adiponectin and fibronectin, adnexa, annex, connect, and interconnect. From NED we also get net and nettles, which were at one time, like hemp, used as a source of fibre. From the lengthened o-grade form NŌD comes the Latin word nodus, a knot, giving us node, nodule, noose, and denouement, which ties things together at the end of a book or drama.

The OED defines “interconnect” as “[to] connect each with the other”; “interconnectedness” is then “the property or state of being interconnected”. Here I mention just two forms of it.

In atomic physics interconnectedness is related to Pauli’s exclusion principle, which states that no two identical particles of matter (fermions) in all the universe may occupy the same quantum state simultaneously. So if you change the quantum state of any fermion, any other fermion that is in the same state, determined by such factors as energy, position, and spin, must also change, and so on. In his sixth Messenger Lecture on the character of physical law at Cornell University in 1963, Richard Feynman said “I think that I can safely say that nobody understands quantum mechanics”. This may be literally true of postmodernists who invoke quantum mechanics as part of their social philosophy. However, what Feynman meant was that nobody understood it in terms of the models of reality with which we are familiar. Atoms for example, do not behave like mechanical models of weights hanging on springs and oscillating. Interconnectedness in the quantum sense cannot be understood in terms of familiar models.

General scientific interconnectedness is easier to understand, and Sokal illustrated its importance in his discussion of homoeopathy, which I shall discuss next week.

Jeffrey Aronson is a clinical pharmacologist, working in the Centre for Evidence Based Medicine in Oxford’s Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences. He is also president emeritus of the British Pharmacological Society.

Competing interests: None declared.