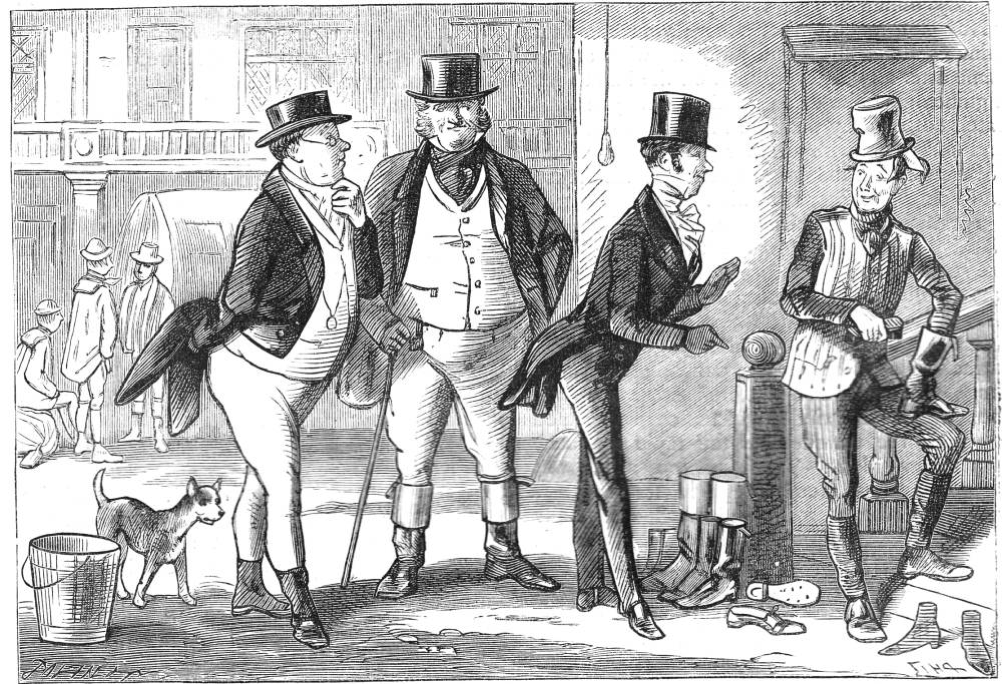

We first meet Sam Weller (picture below) in Chapter X of The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club, which was published serially between April 1836 and November 1837. “He was habited in a coarse-striped waistcoat, with black calico sleeves, and blue glass buttons; drab breeches and leggings. A bright red handkerchief was wound in a very loose and unstudied style round his neck, and an old white hat was carelessly thrown on one side of his head.” Sales of the work had been slow initially, at about 1000 a month, but picked up considerably after Sam appeared, eventually rising to about 40,000 a month. “Some write well,” said a critic, “but Dickens writes Weller”.

We first meet Sam Weller (picture below) in Chapter X of The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club, which was published serially between April 1836 and November 1837. “He was habited in a coarse-striped waistcoat, with black calico sleeves, and blue glass buttons; drab breeches and leggings. A bright red handkerchief was wound in a very loose and unstudied style round his neck, and an old white hat was carelessly thrown on one side of his head.” Sales of the work had been slow initially, at about 1000 a month, but picked up considerably after Sam appeared, eventually rising to about 40,000 a month. “Some write well,” said a critic, “but Dickens writes Weller”.

Dickens describes Pickwick’s hiring of Sam as his manservant (in Chapter XII) as “a very important Proceeding”, not least because, when Pickwick asks his landlady, Mrs Bardell, “Do you think it a much greater expense to keep two people, than to keep one?”, without specifying the second person he has in mind, she thinks that he has proposed marriage, and later sues him for breach of promise.

Sam’s conversation is larded with anecdotes and the bons mots that have come to bear his family name, Wellerisms. A Wellerism is defined in the Oxford English Dictionary as “a speech or expression employed by, or typical of Sam Weller or his father; usu. spec., a form of comparison in which a familiar saying or proverb is identified, often punningly, with what was said by someone in a specified but humorously inapposite situation”. It did not take long for the trope to catch on. The OED cites the Belfast News-letter of 8 September 1837 referring to the form as a Sam Wellerism, and the Macon Telegraph in Georgia, on 2 October 1838, gave the following uninspiring example of what it called a Professional Wellerism: “You are a wery nice man; tisnt every day we see the likes of you, as the heditor said to his subscriber, who called at the office to pay his subscription in hadvance.”

Wellerisms, cousins of Tom Swifties, typically consist of three parts: a statement in the form of a saying, proverb, or quotation; identification of the speaker who makes the statement; and a phrase that casts a new light on the statement, sometimes punningly. “Set down, sir; ve make no extra charge for the settin’ down, as the king remarked wen he blowed up his ministers” (Chapter XLV).

Wellerisms can be inverted and turned into riddles: ‘“What did one tonsil say to the other tonsil?” “Get dressed. The doctor’s taking us out tonight.”’ As Iona and Lionel Opie wrote in The Lore and Language of Schoolchildren (OUP, 1959), these are attractive to children “with their laborious sense of humour.” Truncated versions are also possible: ‘“I see,” said the blind man.

The genre has a long prehistory and features, for example, in the vocabulary of a character, Simon Spatterdash, in a play by Samuel Beazley, “The Boarding House, or Five Hours at Brighton” (1811). For example, “Come on, as the man said to his tight boot.” A later variant invokes the actress and the bishop, always with a sexual connotation, much used by Leslie Charteris. There are eight examples in Enter the Saint (1930) alone, including “I’ve stood as much as I can, as the bishop said to the actress” and “You’re getting on, as the actress said to the bishop.” Others who have used it include John Osborne and Len Deighton. Here’s Kingsley Amis in Lucky Jim (1953): “If you don’t know what to do I can’t show you, as the actress said to the bishop.” Still later variants include “as the art mistress said to the gardener”, “as the girl said to the sailor/soldier”, and “as the Windmill girl said to the stockbroker”. The US version is “Yeah, that’s what she said.”

Here are some medical examples, taken from A Dictionary of Wellerisms, edited by Wolfgang Mieder and Stewart A Kingsbury (OUP, 1994). The puns can be excruciating.

- “We’ll be all right now,” said the doctor, “if we don’t run out of patients.”

- “I only assisted nature, ma’am,” as the doctor said to the boy’s mother, after he’d bled him to death.

- “That will be enough out of you,” said the doctor, as he stitched the patient together.

- “You lie,” as the physician said to his prostate patient, when the latter said he could get up.

- “I’ll spare no pains,” as the quack said when he sawed off his patient’s leg for the rheumatism.

So, if you are foolish enough, before giving someone an injection, to say “Just a little prick,” don’t be surprised if the patient retorts “…as the actress said to the bishop.”

From left to right, Mr Pickwick, Mr Wardle, and Mr Perker (Mr Wardle’s solicitor), with Sam Weller, drawn by Phiz (Hablot Knight Browne); image originally scanned by Philip V. Allingham

Jeffrey Aronson is a clinical pharmacologist, working in the Centre for Evidence Based Medicine in Oxford’s Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences. He is also president emeritus of the British Pharmacological Society.

Competing interests: None declared.