A colleague is sick. Someone is needed to cover him tomorrow. There are no locums and no volunteers. Who should be selected?

A colleague is sick. Someone is needed to cover him tomorrow. There are no locums and no volunteers. Who should be selected?

Few issues generate more passion and cause more heartache to doctors than filling a gap in the rota. Over the Christmas period, it is likely that tears have been shed and friendships lost over who would cover the absent colleague.

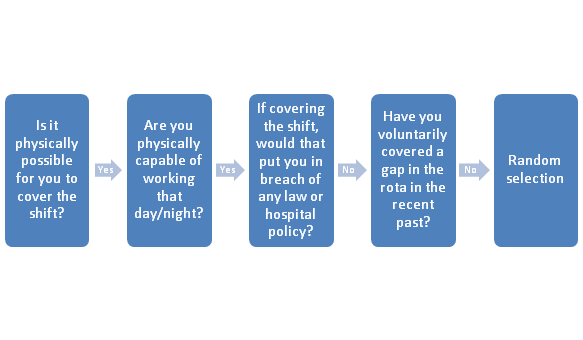

So what is the fairest way to choose?

There are three uncontroversial criteria.

First, the potential candidates must be available. If a candidate is abroad or too far away to make it back in time, he cannot be selected. As the philosopher Immanuel Kant wrote, “ought implies can.” One cannot morally require someone to do something that is not physically possible.

Second, the candidates must be physically able to do the shift. A candidate cannot be selected unless it is safe for both the doctor and the patients. A heavily pregnant doctor, or one who has just done a 24 hour shift, or too intoxicated by drink or other noxious substance, cannot be eligible.

Third, it must be lawful for the candidates to cover the colleague. If doing so will result in the doctor breaching the European Working Time Directive, or some hospital policy, then that rules her out.

The next criterion is more contentious.

If a candidate volunteered to cover a gap in the rota in the recent past, there is a strong moral argument for excluding them from selection. This would act as a reward for such behaviour. This policy may also increase the likelihood of finding volunteers to cover a gap in the rota. If every candidate has volunteered in the recent past, the one who did so the longest ago should be selected.

Whoever remains, I suggest, should be randomly chosen. Young children, needing to hire a babysitter, a spouse threatening divorce, a family reunion, an impending exam, or a longer commute to work should not exclude a doctor from the selection process. As these factors are controversial, including them in the process is likely to cause resentment and damage morale. It would also raise further difficulties: is having two children worth more “points” than one? Is a baby worth more or less than a five-year-old? How real should the threat of divorce be? How close does the exam have to be?

Finally, it is important to raise the issue of honesty. Some doctors will lie to avoid selection. They will claim to be at the other end of the country when they are nearby. They will say they are too drunk to work the next day. They will make up excuses. These are not “white” lies. They breach the General Medical Council’s rule that doctors shall be “honest and trustworthy.” Lying to avoid selection is unprofessional, breaches trust, and could lead to unfairness in the selection process. It represents a betrayal of your colleagues.

So here is one ethicist’s flowchart for selecting a replacement for the rota, assuming there are no volunteers and no locum is available.

Rota problems often raise broader issues, which include staffing, compliance with the European Working Time Directive, Trusts’ willingness to find locums and pay sufficient hourly rates for covering gaps in the rota, and perhaps even the loss of the esprit de corps that once characterised the medical profession. Those matters, which underlie the very practical problem addressed in this column, are for another time.

Daniel Sokol is a medical ethicist and barrister at 12 King’s Bench Walk, London.