I don’t know why I let Jeremy Hunt, the BMA, and Acas get in the way last week, when I was progressing with my exploration of different types of twisting.

I don’t know why I let Jeremy Hunt, the BMA, and Acas get in the way last week, when I was progressing with my exploration of different types of twisting.

As I was saying, several Indo-European roots connoted twisting and turning. I began with UER and then made a start on PLEK, but there’s more to say about the latter.

Grimm’s law, propounded by Jacob Ludwig Grimm, one of the Grimm brothers, more famous for their collection of twisted fairy tales, governs the ways in which particular sets of consonantal phonemes change from one to another as languages develop, explaining certain Latin/English and Greek/English correspondences. The interchanging sets are:

• the velars k, g, and h, explaining cardia/heart, genu/knee, and hostis/guest;

• the dentals t, d, and th, explaining tres/three, duo/two, and thyroid/door;

• the labials p, b, and f, explaining pes/foot, labia/lip, and fundamentum/bottom.

In Greek PLEK gave πλεκ- and πλο(κ)-, and in Latin plec- and plic-. It implied not only to twist, but other twisty actions as well—to braid or weave, to bend or fold. Folding also implied repetition. However, because of Grimm’s law, PLEK also gave words in which the p was replaced by b or f.

The b forms are related to duplex and duplicate, folded in two, giving double. A doubloon was a Spanish gold coin that was originally double the value of a pistole, i.e. about 35 shillings (£1.75) in old money, although, if you can find one, worth much more today.

The f forms are more numerous. Some have suggested that a flask is so called because it was originally a bottle around which straw and the like was twisted, but this seems unlikely. Other suggested derivations invoke the Greek ϕῐάλη, a bowl or a pan, and Latin vasculum, a small vessel, the diminutive of vas. These suggestions, both of which imply Grimm-type conversion from PLEK to FLA and then metathesis to FAL and back again, are scarcely more convincing than the straw hypothesis, and the whole business seems to me to be something of a fiasco.

Better attested is flax, with its woven fibres, although some have suggested an alternative source, not PLEK but PLEIK, to tear, giving flay, fleck, flesh, and flitch, implying the stripping process by which flax is prepared. Floss, the rough material that envelops the cocoon of the silk worm may also be related, but who knows? It is more probably related to plush fabrics and a post-classical Latin word pellutium, short fine wool, or a word meaning to untangle hair, like plucking.

We do know, however, that the Latin word flectere, to bend, gave us flexibility, flexor muscles to flex, flexures in the skin and large bowel, reflexes nervous and red, reflections mental, pericardial, pleural, and peritoneal, retroflexion of the uterus, inflections linguistic and mathematical, and circumflex accents, arteries, nerves, and muscles.

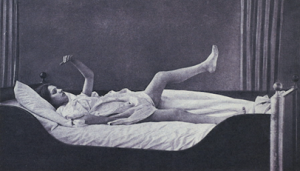

Images: Cases of waxy flexibility (left) and catalepsy (right)

Waxy flexibility, or in Latin flexibilitas cerea, is a condition in which an individual remains in the same position for an unusually long period of time and may stay there until moved by someone else (picture). It is typically a manifestation of catatonic schizophrenia. Although it is sometimes used as a synonym for catalepsy (Greek κατάληψις, seizing or grasping), it is not the same. Catalepsy is characterized by muscular rigidity and a fixed posture, with reduced sensitivity to pain. It occurs in conditions such as Parkinson’s disease and epilepsy and as an adverse reaction to neuroleptic drugs in schizophrenia. However, waxy flexibility can occur in patients with catalepsy. Even more confusingly, cataplexy, which occurs in narcolepsy (Gélineau’s syndrome), is sudden transient loss of muscle power while fully conscious, typically triggered by emotions such as laughing, crying, and terror.

Alert readers, as both of them are, may have thought that this brings us back twistingly, full circle, to PLEK, but cataplexy (κατάπληξις) comes from a different root altogether, something to do with striking. Now that does bring us back full circle.

Jeffrey Aronson is a clinical pharmacologist, working in the Centre for Evidence Based Medicine in Oxford’s Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences. He is also president emeritus of the British Pharmacological Society.

Competing interests: None declared.