As a medical student I got a parking ticket and three points on my driving license. The mistake I had made was parking in the wrong place on an unmarked road in the Peak District. When I sent in my fine I wrote a short note along the lines of, “I realise that being ignorant of this law is not a valid defence.”

As a medical student I got a parking ticket and three points on my driving license. The mistake I had made was parking in the wrong place on an unmarked road in the Peak District. When I sent in my fine I wrote a short note along the lines of, “I realise that being ignorant of this law is not a valid defence.”

For what it is worth, there has been a stir in social media this week over the publication of a survey carried out by ResilientGP, a fledgling organisation that purports to “stand up for general practitioners.” The organisation argues that one of the stressors in primary care, and there are many, is the unnecessary use of the NHS by patients with problems that seem unconnected to any health problem.

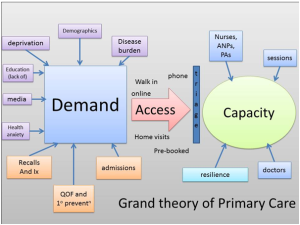

The list can make for uncomfortable reading. Some have found it hilarious. Yet others have found it outrageous that the ignorance of patients has been laid bare for people to see. The survey raises some important questions to ask though, and unfortunately I don’t think I can offer any answers. However, the purpose of the survey was to address the issue of patient demand and contributing factors towards it.

Firstly, is unfettered and unchecked patient demand, which leads to what some would consider inappropriate use of GP time, an important stressor in general practice? In some ways, it is a relief to get someone coming in asking what their xiphisternum is, or the lumps above their waist when they wear tight jeans (love handles), as these consultations take a short amount of time and help me to keep to time—just like patients that do not attend (DNAs). However, the opportunity cost, just like DNAs, is that the appointment slot used is not available for someone with genuine medical need.

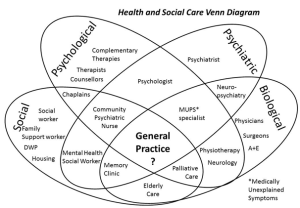

Added to that is a general practice workforce that is likely to be the most regulated, most monitored, and who are expected to do everything from spotting potential religious extremists to assessing patients’ homes for new boilers. I would add that the extra frustration of having to deal with inappropriate consultations, as with DNAs, simply compounds the retention and recruitment crisis that is affecting general practice.

The next questions are whether this use of the NHS is significant in its effect on doctors and nurses, and whether the impact on access—the holy grail of politicians—is also affected? Perhaps this survey has started a debate that is avoided by those who are elected, because of its potential to be unpopular.

The next logical question is, “How do you define what is appropriate?” This list was simply put together by doctors, based on their own thoughts, feelings, and assumptions. One would hope that patient groups would be interested in defining what is appropriate and therefore which patients can be told, “This has been a waste of my time and yours”—something which doctors probably avoid doing for fear of complaint or negative feedback on friends and family tests.

I would argue that a societal question that needs answering is, “Can you go to see your GP about absolutely anything, anything at all?” If the answer is yes, then we’ll need more GPs and funding to match. If the answer is no, then we have to go about tackling these difficult questions. How general do we want general practice to be?

Although some cases of inappropriate attendances are fuelled by health anxiety—which is another complex issue—some are simply down to ignorance, or perhaps even a lack of other options. Is ignorance a valid defence for patients? Or is every consultation, no matter how seemingly unimportant, part of a bigger relationship? Can the NHS afford that?

Do GPs and their availability exist for those without medical need? Do they exist for those without medical need, in the hope that a brief interaction will contribute positively to an episode of theoretical future care?

I would argue that we need to start by taking the bull by the horns: deciding for ourselves what we can and can’t deal with, and telling patients where our boundaries are—for the sake of the rest of our practice population (the opportunity cost), our own wellbeing, and to educate our patients. It is my understanding that the ambulance service gives examples of inappropriate use of its finite resources. Hopefully by doing the same, ResilientGP has sparked a debate about the use of GP resources, which ultimately are also limited and finite.

Samir Dawlatly is a GP partner at Jiggins Lane Surgery in Birmingham. He combines clinical practice with being a part time house husband and an interest in social media, as well as publishing poems, essays, and blogs. He can be found on Twitter as @sdawlatly.

I have read and understood BMJ policy on declaration of interests and declare the following interests: I am a member of the RCGP online working group on overdiagnosis. I am a member of the Resilient GP Facebook group. I have made a single donation of money to the Resilient GP Partnership and provided material for their blog.