Authors: Alex Rowlands and Mark Orme

Why is this study important?

Wearable activity monitors are increasingly used to assess how physically active people are. The intensity of physical activity measured by these devices is usually expressed in absolute terms. For example, time spent above a given rate of energy expenditure (e.g., 3 metabolic equivalents (METs), defined as moderate), or above a walking speed (e.g., 3 mph).

However, this approach does not account for an individual’s physical capacity; that is, walking at 3 mph may be perceived as light (or easy) by a person with high fitness, but vigorous (or hard) by a person with low fitness. Expressing the intensity of a person’s physical activity relative to their physical capacity reflects how hard activities feel to that person.

Clinical studies typically use relative intensity, e.g., prescription of intensity based on heart rate or rating of perceived exertion (RPE), while epidemiological studies typically use absolute intensity. This difference in how intensity is defined may impact on the applicability of epidemiological findings in clinical settings.

We have previously developed open-source tools that use data from wearable activity monitors to express the intensity of a person’s physical activity relative to their physical capacity. In this study, we apply these methods to determine whether epidemiological findings differ depending on whether absolute or relative intensity is measured. We considered: (1) age-related differences in physical activity; and (2) associations with mortality.

How did the study go about this?

We used data from 11,463 participants of the UK Biobank study, aged 43-76 years, who had their cardiorespiratory fitness (physical capacity) measured and who wore an activity monitor for up to 7-days. We used performance on the fitness test to determine each person’s maximum physical activity level. We then expressed the intensity of their daily physical activity relative to this maximum level.

For participants who died during the ~8-years since their activity was measured, we obtained the date of death from NHS records.

What did the study find?

Age differences in physical activity and associations with mortality differed depending on whether intensity was expressed in absolute terms or relative to a person’s physical capacity.

- The absolute intensity of people’s daily physical activity declined by age. However, the relative intensity of daily physical activity was similar across age. Thus, despite older people doing less activity, they were just as active as younger people relative to their physical capacity.

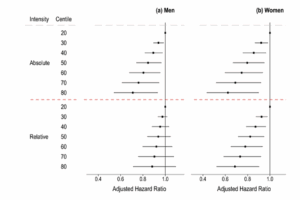

- For women, either higher absolute intensity or higher relative intensity of physical activity was associated with lower rates of mortality. However, in men, only higher absolute intensity of physical activity was associated with lower rates of mortality.

What are the key take-home points?

It matters whether the intensity of physical activity is measured in absolute terms or relative to a person’s capacity. Thus, it is important to consider how activity intensity is defined when applying findings from epidemiological studies to clinical settings.

Assessing physical activity based on absolute intensity overestimates moderate intensity activity in younger (and/or healthy) populations and underestimates moderate intensity activity in older (and/or less healthy) populations.

Daily physical activity profiles including 30 minutes of walking at >3.5 mph (or >110 steps/min) were associated with the lowest mortality risk in men and women. In women only, daily physical activity profiles with 20 minutes at or above a RPE of 12–14 were also associated with a low risk of mortality.