Part 2 – Management & Infographic

Management

Many factors need to be taken into account when determining the approach to managing a Moral-Lavallee lesion. Different management forms include conservative treatment, minimally invasive treatment, and surgical intervention.

Conservative approach

Lesions with small fluid collections and no overlying pressure changes may be managed by conservative means such as compression bandaging. (6)

Tight compression bandaging is vital as a form of primary treatment and as an adjunct. For hip lesions, tight cycling shorts may help reduce recurrence.

Patient education is imperative; patients should be educated on how to re-bandage and be given adequate safety-netting advice on recognising the signs of infection.

Minimally invasive – Aspiration

Aspiration may be used on acute lesions with fluid below 50ml as the recurrence of fluid collection is appreciably more common in lesions above 50ml. (6)

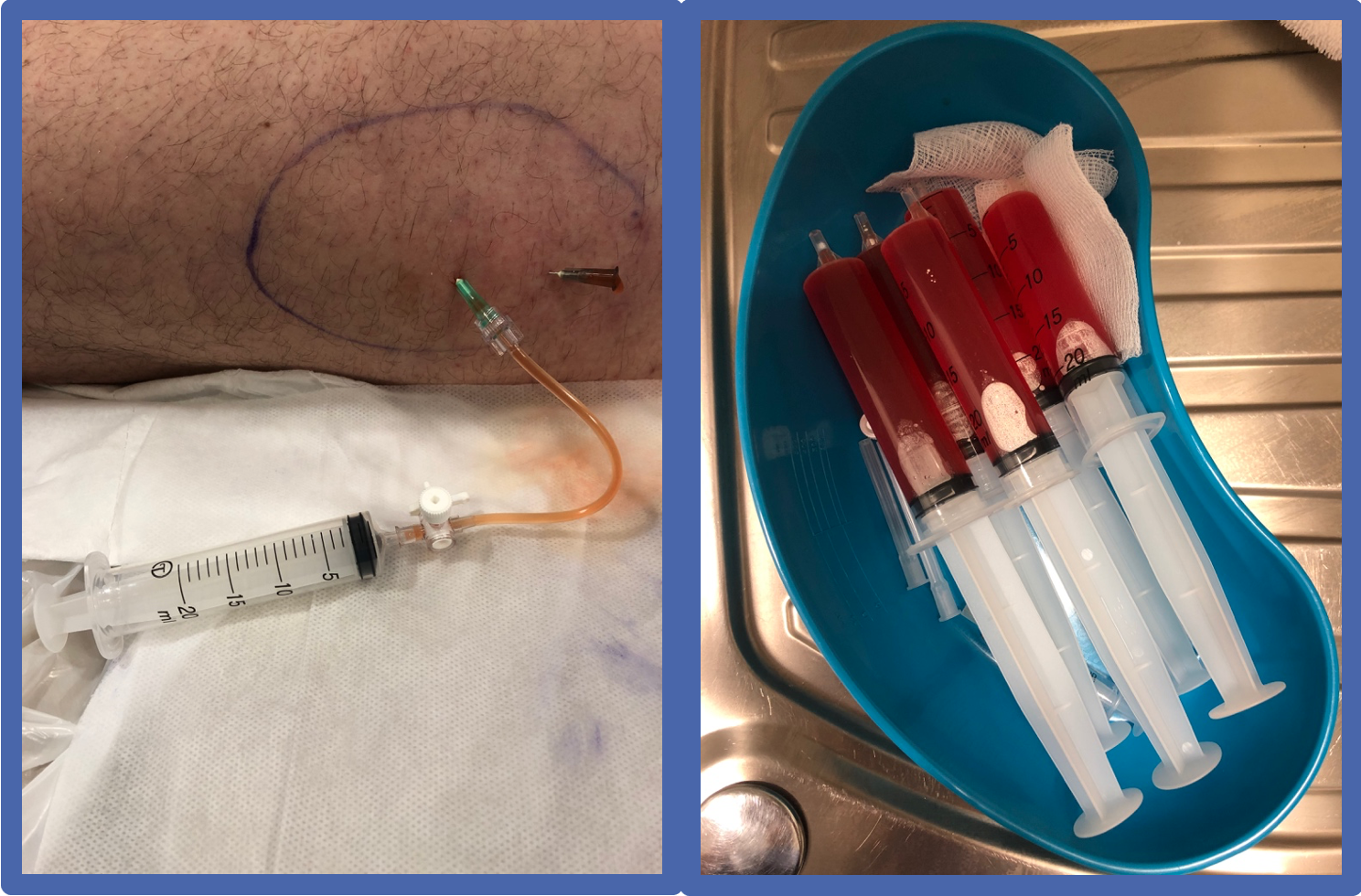

Aspiration can be performed in a lateral decubitus or supine position, with the patient lying on the contralateral asymptomatic hip. The aspiration is performed under ultrasound guidance, using a sterile technique and a large-bore needle, 20-50ml Luer-lock syringe, and 3-way tap.

Aspiration from the caudal to the cranial direction risks creating a fistula as fluids continue to seep out of the tract due to gravity.

The MLL is aspirated to dryness, if possible, and then compressed with an elastic dressing such as Coban around the upper thigh. This can be worn for 3 or more days.

The patient should be advised to undertake relative rest for several days and consider offloading with crutches initially.

The patient should then be reviewed in 5 weeks for consideration of a further aspiration if required as the fluid tends to reaccumulate. This time duration is merely a guide as it can vary from patient to patient. It takes an average of 5 weeks for the complete resolution. It takes an average of 5 weeks for complete resolution, which should be confirmed by looking for the complete absence of any free fluid on ultrasound of the affected region. (7)

Minimally invasive – Sclerodesis

This approach is often used where aspiration fails. A sclerosant pharmacologic agent can be used to close off pathological cavities via the induction of fibrosis through the destruction of the cells lining the cavity. This process will prevent the fluid collection and reduce the risk of recurrence post aspiration.

Doxycycline is currently the most researched sclerosant agent as it is highly effective and financially viable. The protocol designed by Bansal et al. uses a solution of 500 mg doxycycline in 25 ml 0.9% saline, which is autoclaved at 121 °C for 15 min. This is shown to be effective in lesions up to 400ml. (7) Dextrose is another potential alternative; the solution should consist of an equal mixture of 50% dextrose and normal saline. Other agents such as Bleomycin, Talc and Hyaluronidase have been proposed. Bleomycin is expensive and, therefore, may not be readily accessible. Talc necessitates the need for general anaesthesia and can cause severe pain. (7) The practitioner should aim to touch lesion walls but not overfill them. Hyaluronidase is an enzyme that breaks down hyaluronic acid. It is used to increase the absorption of drugs into tissue and reduce tissue damage where there is extravasation of a drug.

Surgical intervention

Surgical intervention may be the first line or last line treatment for an MLL, depending on the injury’s context.

Indications for surgical management include

- Infection – an open debridement of the lesion will be required.

- Underlying fracture – fixation will be necessary.

- Chronic lesions – formation of pseudo capsules pose a hindrance to conservative and minimally invasive treatment and will likely require surgery. These lesions can also be an issue from an aesthetic perspective.

- Unsuccessful non-surgical treatment.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The idea for this series of narrative blogs arose from a clinical case discussion of the Pure Sports Medicine Consultants group- this comprises specialists in Sport, Exercise & Musculoskeletal Medicine; Rheumatology & Rehabilitation Medicine. We wish to thank all our colleagues for their contributions and valuable tips which arose during these discussions.

Declaration of interests: All the authors declare that they have no known established conflicting financial interests or personal relationships that may have influenced the facts or academic aspects presented in this series of narrative blogs.

AUTHORS:

Richard Seah1,2,3, Michael Burdon1, Petros Akin-Nibosun4, James Thing1,5,6, Anthony Waring1,7

Author affiliations:

1Pure Sports Medicine, London, UK

2Institute of Sport, Exercise & Health (ISEH), London, UK

3Royal National Orthopaedic Hospital NHS Trust, Stanmore, Middlesex, UK

4Medway Maritime Hospital, Medway NHS Foundation Trust, Gillingham, Kent, UK

5One Welbeck, London, UK

6The Joint Injection Clinic, London, UK

7Fortius Clinic, London, UK

Correspondence to:

Dr Richard Seah, Pure Sports Medicine, Canary Wharf, London E14 4QT, UK; rick.seah@puresportsmed.com

REFERENCES

- Morel-Lavallée VAL: Decollements traumatiques de la peau et des couches sous jacentes. Arch Gen Med. 1863;1:20-38, 172-200, 300-332

- Diviti S, Gupta N, Hooda K, Sharma K, Lo L. Morel-Lavallee lesions-review of pathophysiology, clinical findings, imaging findings and management. Journal of clinical and diagnostic research: JCDR. 2017 Apr;11(4):TE01.

- Scolaro JA, Chao T, Zamorano DP. The Morel-Lavallée lesion: diagnosis and management. JAAOS-Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2016 Oct 1;24(10):667-72.

- Vanhegan IS, Dala-Ali B, Verhelst L, Mallucci P, Haddad FS: The Morel-Lavallée lesion as a rare differential diagnosis for recalcitrant bursitis of the knee: Case report and literature review. Case Rep Orthop 2012; 2012:593193.23320230

- Suzuki T. Postoperative surgical site infection following acetabular fracture fixation. Injury 2010;41(4):396-399.20004894

- Nickerson TP, Zielinski MD, Jenkins DH, Schiller HJ. The Mayo Clinic experience with Morel-Lavallée lesions: establishment of a practice management guideline. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2014; 76:493–7.

- Bansal A, Bhatia N, Singh A, Singh AK. Doxycycline sclerodesis as a treatment option for persistent Morel-Lavallée lesions. Injury. 2013 Jan 1;44(1):66-9.

- Figure 1 created by Biorender.com

- Figure 2 taken with permission from Bonilla-Yoon I, Masih S, Patel DB, White EA, Levine BD, Chow K, Gottsegen CJ, Matcuk GR. The Morel-Lavallée lesion: pathophysiology, clinical presentation, imaging features, and treatment options. Emergency Radiology. 2014 Feb;21(1):35-43.