Introduction

- Hand osteoarthritis (OA) is a common presentation in the musculoskeletal (MSK) clinic, impacting millions of patients worldwide.

- It typically presents with pain, stiffness, and a significant reduction in joint function, which collectively disrupt daily activities and patients’ quality of life.

- To effectively manage hand OA, MSK clinicians must be adept at diagnosing the condition and distinguishing it from similar disorders such as rheumatoid arthritis, calcium pyrophosphate deposition (CPPD) and gout.

- In this blog, we discuss the key patterns of joint disease to be aware of, and what future treatments are on the horizon.

What do we know about hand OA?

- Despite the high prevalence of hand OA, we are still understanding the exact mechanisms of its disease progression and trying to identify the most effective mechanism-based therapies for treatment.

- As with other forms of OA, current research is pointing towards a complex interplay of genetic, metabolic, and lifestyle factors that influence disease progression.

- Increasing life expectancy, and obesity rates, are two factors that are projected to increase the prevalence of OA globally (1).

- Research on hand OA is still ongoing to help us evaluate clinical scoring systems, and criteria to assess the severity and how the disease may progress over time (prognosis) (2).

Figure 1: Hand osteoarthritis summarised

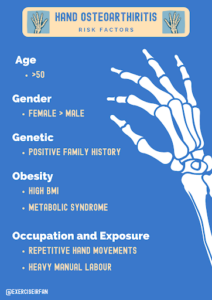

Who gets it?

The prevalence of hand OA in adults varies, by age sex, family history and trauma history!

- Symptomatic hand OA prevalence in adults (2.0-6.2%) (3).

- Symptomatic hand OA prevalence in elderly adults (4.7-20.4%) (3).

- Hand OA (prevalence) women>men.

- Previous history of trauma (fracture or intra articular injury) and repetitive manual tasks are associated with an increased risk of Post traumatic OA (4).

- Post traumatic OA may account for up to 12% of all cases of Osteoarthritis (4).

How common are X-ray changes in older adults?

- Radiographic osteoarthritis (ROA) in at least one hand joint is observed in 67% of women and 54.8% of men aged 55 years and older (5).

Figure 2: Risk factors for OA

Classifying hand OA and typical X-ray changes seen

Hand osteoarthritis (OA) – The Typical pattern defines by (EULAR) (6)

Figure 3: X-ray hand OA – base of thumb

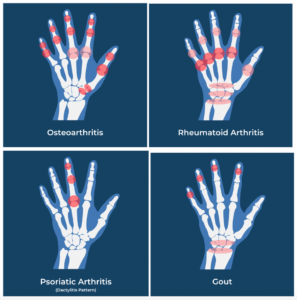

Hand Arthritis the pattern of joint disease; tells the tale!

Figure 4: Joint distribution of hand arthritis

Plain X-rays features, as classified by the Kellgren and Lawrence system, are used to evaluate hand OA patterns. The presence of “osteophytes, joint space narrowing, sclerosis and bone deformity at the joint line” are all key criteria. Osteophytes are the most common but least specific, x-ray feature of hand OA.

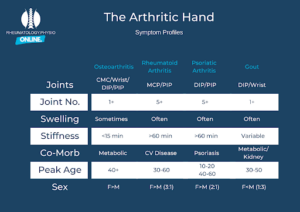

Unpicking Hand OA from key differentials in clinic!

“Hand pain” is common presenting complaint in clinic, and the diagnosis can be made based upon a focused history that considers the:

- speed on onset

- diurnal variation (pattern through the 24-hour day)

- effect of movement and load,

- the number and location of joints involved,

- the patient’s profile (genetic predisposition, occupation, metabolic profile)

- systemic symptoms.

Figure 5: The Arthritic Hand

Hand OA: can start in a single joint (monoarthritis) or present in a more widespread pattern (polyarthritis). Symptoms usually start insidiously and much slower than inflammatory or crystal–arthritis (arthropathy). Changes tend to occur in a row across joints, at the same level (e.g. distal interphalangeal joint) with common signs such as (Heberden’s or Bouchard nodes) but the MCP’s are usually spared.

Key give aways in the history of OA

- Pain related to activity.

- Pain is worse with repetitive movements or forceful heavy movements.

- Short lived morning stiffness (typically, < 15 mins)

- Nocturnal discomfort

- Quiet joint line (minimal redness, swelling or heat)

In more severe cases

- Loss of joint function, and significant deformity,

- Often accompanied by OA symptoms to other large joints (Hip/ Knee)

Figure 6: Hand OA features

Using imaging to unpick the causes of hand pain

MSK imaging can be useful to help you determine which structures could be driving the pain.

1. X-ray

- The most widely used imaging modality for hand pain.

- Although not essential for the diagnosis of hand OA, it can help to define the number and pattern of joints affected.

2. Ultrasound – good for assessing soft tissue structures,

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Used to detect early signs of synovial hypertrophy, joint tissue swelling/oedema, osteophytic lipping and inflammation (power doppler signal).

- Erosions may also be seen in later disease.

- Peripheral spondyloarthropathies

- Used to detect extra-articular changes in peripheral spondyloarthropathies (tenosynovitis & enthesis).

- Crystal arthropathies

- Used to detect, tophi, double contour sign & snowstorm appearance of synovial fluid

3. MRI – Good for assessing soft tissue structures, and inflammation/ infection. This imaging modality is expensive and not easily available.

Although not required for the diagnosis of hypermobility syndrome or fibromyalgia, the use of imaging in clinic (Point of care ultrasound) where available can be considered for patient education. To demonstrate that joint movements are unrestricted, and no significant pathology is visible of the joint or soft tissue structure.

| Condition | Key features/ risk factors | Diagnosis | Gold Standard investigation (if any) |

| Rheumatoid Arthritis | FH of rheumatoid arthritis.

Smoking history Middle age presentation |

Rheumatoid factor (positive status) – sensitivity 41%–66% for early RA.

Rheumatoid factor – has higher sensitivity in established disease. Anti-CCP positive status linked with higher disease activity/ inflammation. |

Clinical history + Anti-CCP – positive status |

| Gout [7] | Metabolic syndrome features.

Positive family history in early onset disease. |

MTP joint, acute inflammation (<1 day onset of maximum pain)

Elevated serum urate >360mmol + clinical features of gout flare. Tophi + Positive fluid aspirate Positive DECT scan (sens 81% spec 88%)- in chronic/challenging cases |

Clinical history and hyperuricemia or positive joint aspiration (Negative birefringent crystals) |

| PsA | f/h of PsA | Accepted criteria (CASPAR) | Combination of clinical history and imaging features. |

| OA [8] | f/h

manual job/hand dominant sport |

Can be made on clinical history

But imaging features can be used to support the diagnosis/pattern of disease (Xray/US) US more specific for early-stage disease. |

X-ray changes. |

| Pain sensitisation / fibromyalgia | Widespread pain

hypermobility |

Clinical

Imaging can be used to exclude other diagnosis. |

Imaging often normal, or only age-appropriate changes seen. |

Figure 7: X-ray displaying features of gout

| Condition | Best modality for Early disease | Key Xray findings | Key US findings | Key MRI findings | Other imaging tests |

| Rheumatoid Arthritis (9) | US

MRI not routinely used but can help to diagnose this |

Articular erosions

Ulnar deviation (advanced) |

Synovitis

Power doppler signal Erosions |

Synovial hypertophy/synovitis,

Bursitis/bursal hypertrophy Tenosynovitis/tenosynovial hypertrophy bone marrow oedema (precedes erosions) |

Nil |

| Gout | US | Periarticular erosions | Gouty tophy (shimmer sign)

Double contour sign(less reliable) Snowstorm sign |

Synovitis

Tophi |

DECT scan |

| PsA (10) | US | Marginal erosions with hypertrophy in typical patterns | Synovitis

Flexor tenosynovitis ECU tenosynovitis Enthesitis |

Synovial hypertrophy | Nil |

| OA (11) | US | Joint space narrowing, Subchondral sclerosis, osteophytes | Osteophytes,

Synovial hypertrophy, Atrophy of fibrocartilaginous complex |

Loss of articular cartilage | Nil |

| Pain sensitisation | Nil | Normal | Nil | Nil | Nil |

| CRPS | Nil | May show localised osteopenia | Nil | May show bone marrow oedema | Nil |

Treatments – Starting with patient education and hand therapy

Clinical treatment for Hand Osteoarthritis primarily focuses on maintaining function, through joint range, strength and supporting the use of the upper limb. It is important to consider the patient’s occupational demands and hobbies as part of treatment goals. The use of low stress environments such as warm water, hand putty, or wax therapy can be trialled.

Joint supports (1st CMC brace and gel caps for DIP joints) can impact range of motion and be cumbersome with movement. It is important to counsel patients on regular breaks from repetitive tasks and positioning techniques to reduce stress on symptomatic joints. Reducing systemic inflammatory factors such as smoking cessation, weight loss, optimised sleep and stress reduction can be helpful in the long term.

Preventing Hand injuries in sports

Traumatic hand injuries commonly occur in combat sports & ball sports where contact is made with the hand (e.g., basketball, volleyball, and goalkeepers in football (13). Common injuries include:

- fractures (e.g., phalangeal, metacarpal, carpal),

- ligamentous injuries (e.g., scapholunate, collaterals, CMCJ, and knuckle sagittal bands)

- tendon ruptures (e.g., jersey finger, mallet finger, central slip, and pulley injuries in rock climbers) (13)

Figure 8: Common hand injuries

Taping strategies are an effective way to minimise hand injuries in sport?

Injury prevention strategies for hand trauma should look to identify the intrinsic and extrinsic factors of each “at risk” sport. The most employed strategy is external “taping” across the small and large joints of the hand to reduce the forces transmitted to the hand. The location and distribution of taping varies by each sport, discipline and the rules governing the level of support allowed during competition.

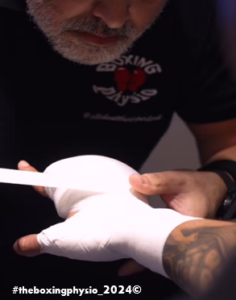

Some sports have quite visible distinctive preventative taping (e.g. digits in volleyball or rugby, or the entire hand-wrist in boxing, which is then fitted in a glove). In boxing, adding tape provides a 25-30% reduction in wrist motion, placing the hand in a better position to withstand forces and thereby reducing the likelihood of injuries (14, 15).

Figure 9: Taping strategies

Medications

| Medication Type | Indications | Benefits | Potential Side Effects | Guideline Recommendations |

| Paracetamol (PCM) | Initial mild to moderate pain | Well-tolerated, easy to access | Limited efficacy, liver toxicity at high doses | Use with caution, limited benefits observed |

| Topical NSAIDs | Localized mild to moderate pain | Effective, fewer systemic side effects | Skin irritation, minimal systemic absorption | Recommended for initial treatment, especially in patients with comorbidities |

| Oral NSAIDs | More severe pain | Strong anti-inflammatory and pain relief | Gastrointestinal, cardiovascular, renal risks | Use if topical NSAIDs are inadequate, monitor for side effects |

| Opioids | Severe pain, other treatments ineffective | Potent pain relief | Nausea, vomiting, dizziness, dependency | Not generally recommended due to risk of adverse effects |

| Steroid Injections | Severe inflammation | Rapid relief from pain and inflammation, some placebo effect | Temporary relief, potential for joint damage | Consider if other medications fail; limit frequency of use |

Specialist Hand OA treatment

Early onset OA (<40 yrs of age) needs specialist input as secondary causes e.g. haemochromatosis, hypermobility syndromes and connective tissue disorders such as stickler syndrome need to be considered. Such patients usually have comorbid symptoms of diabetes, joint subluxations, ocular or auricular complications. Similarly, inflammatory or erosive OA may have associated underlying conditions e.g. primary hyperparathyroidism or calcium pyrophosphate disease (CPPD). In such cases, the specialists may consider short courses of corticosteroids, colchicine or intra-articular injections. Though there is no role of conventional or biological disease modifiers as employed in inflammatory arthritides, in cases of co-existing CPPD arthritis, there is limited data of their utility.

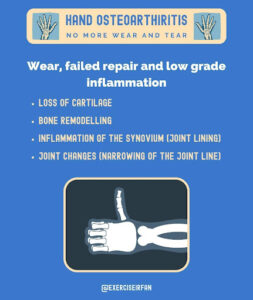

The Latest Evidence on what drives OA – What is coming?

OA was traditionally considered a “wear and tear” disease, but recent evidence has expanded this concept to “wear, failed repair, and low-grade systemic inflammation.” It helps to frame discussions around the impact, of lifestyle interventions as part of treatment plans, and how weight loss and other health intervention can reduce symptoms. In the long-term preventing failed repair mechanisms are key to OA (12).

Figure 10: Features of hand osteoarthritis

Hand OA – Break down and failed repair at the joint

- OA leads to an inflammatory environment at the joint surface (16).

- OA leads to Higher chondrocyte activity (16).

- OA leads to a cycle of cartilage breakdown, and loss of protection to mechanical stress (16).

- OA leads to thickening of the joints synovial lining (often seen on ultrasound) & an increase in cellular inflammatory signals (17).

What’s new with hand OA treatments.

Thanks to improved understanding of factors associated with OA progression, several disease modifying osteoarthritis drugs (DMOADs) have been trialled to prevent further structural deterioration, restore joint structure, and improve symptoms. Therapeutic mechanisms are based on stimulating cartilage growth by inducing anabolic factors e.g. fibroblast growth factor-18, transforming growth factor beta1, reducing joint degradation by inhibiting catabolic factors e.g. Wnt pathway or Cathepsin K inhibitor and abrogating inflammation with IL-10 induction or IL-1 downregulation. The dawn of mechanism-based targeted therapies is promising and provides hope of addressing the unmet therapeutic needs of hand OA.

Conclusion – 4 key points

- Hand OA – is linked to – “Wear, Failed repair and low-grade inflammation” at the joints of the hand.

- There are increasing links between, metabolic risk factors (diabetes / obesity) and the progression of hand OA.

- A focussed assessment, to include the pattern of pain, joint involved and medical history can help to unpick OA from other causes of hand pain.

- Currently there are no biological therapies for hand OA. but this is a future area of research.

References

- Cross M, Smith E, Hoy D, et al. (2014). The global burden of hip and knee osteoarthritis: estimates from the global burden of disease 2010 study. Annals of Rheumatic Diseases, 73, 1323–1330.

- Altman R, Asch E, Bloch D, et al. (1986). Development of criteria for the classification and reporting of osteoarthritis: Classification of osteoarthritis of the knee. Arthritis and Rheumatism, 29, 1039–1049.

- Kloppenburg M, Kwok WY. (2011). Hand osteoarthritis—a heterogeneous disorder. Nature Reviews Rheumatology, 8, 22–31.

- Dilley JE, Bello MA, Roman N, et al. (2023). Post-traumatic osteoarthritis: A review of pathogenic mechanisms and novel targets for mitigation. Bone Reports, 18. doi: 10.1016/J.BONR.2023.101658

- Dahaghin S, Bierma-Zeinstra SMA, Ginai AZ, et al. (2005). Prevalence and pattern of radiographic hand osteoarthritis and association with pain and disability (the Rotterdam study). Annals of Rheumatic Diseases, 64, 682–687.

- Zhang W, Doherty M, Leeb BF, et al. (2009). EULAR evidence-based recommendations for the diagnosis of hand osteoarthritis: report of a task force of ESCISIT. Annals of Rheumatic Diseases, 68, 8–17.

- Jia E, Zhu J, Huang W, et al. (2018). Dual-energy computed tomography has limited diagnostic sensitivity for short-term gout. Clinical Rheumatology, 37, 773–777.

- Solivetti FM, Elia F, Teoli M, et al. (2010). Role of Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasound in Early Diagnosis of Psoriatic Arthritis. Dermatology, 220, 25–31.

- Terslev L, Naredo E, Aegerter P, et al. (2017). Scoring ultrasound synovitis in rheumatoid arthritis: a EULAR-OMERACT ultrasound taskforce-Part 2: reliability and application to multiple joints of a standardised consensus-based scoring system. RMD Open, 3, 427.

- Leung YY, Tillett DW, de Wit M, et al. (2023). Initiating Evaluation of Composite Outcome Measures for Psoriatic Arthritis: 2022 Updates From the GRAPPA-OMERACT Working Group. Journal of Rheumatology, 50, 53–57.

- Sensitivity of radiographic features and specificity of scintigraphic imaging in hand osteoarthritis. PubMed (accessed 9 June 2024).

- Hunter DJ, Bierma-Zeinstra S. (2019). Osteoarthritis. Lancet, 393, 1745–1759.

- Simpson AM, Donato DP, Veith J, et al. (2020). Hand and Wrist Injuries Among Collegiate Athletes: The Role of Sex and Competition on Injury Rates and Severity. Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine, 8(12). doi: 10.1177/2325967120964622

- Gatt IT, Allen T, Wheat J. (2023). Effects of using rigid tape with bandaging techniques on wrist joint motion during boxing shots in elite male athletes. Physical Therapy in Sport, 61, 82-90. doi: 10.1016/j.ptsp.2023.03.002

- Avery DM 3rd, Rodner CM, Edgar CM. (2016). Sports-related wrist and hand injuries: a review. Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery and Research, 11(1):99. doi: 10.1186/s13018-016-0432-8

- Loeser RF, Goldring SR, Scanzello CR, et al. (2012). Osteoarthritis: a disease of the joint as an organ. Arthritis and Rheumatism, 64, 1697–1707.

- Scanzello CR, Goldring SR. (2012). The role of synovitis in osteoarthritis pathogenesis. Bone, 51, 249–257.