Key words: ACL, muscle strength, rehabilitation, hip

This blog summarises the findings from a recent systematic review on hip and lower leg strength after anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injury) (1).

Why is this study important?

Muscle weakness is a key target of ACL injury rehabilitation, and strength deficits of the knee muscles (quadriceps and hamstrings) are often as high as 10-20% compared to uninjured controls, even several years after injury. However, less is known about muscle strength of the hip and lower leg (calf). Hip and lower leg muscles are crucial to many functional tasks and sporting activities (e.g., hopping, jumping). All existing evidence was reviewed to provide a single go-to summary of hip and lower leg strength for clinicians and researchers.

How did we go about this?

We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of all studies that measured hip and/or lower leg strength after primary (first time) ACL injury. Participants were aged 18-40 years at the time of injury, but no other restrictions were placed on the people included. Muscle strength had to be measured with a hand-held or computerised (isokinetic) dynamometer. Studies had to report muscle strength for the ACL limb compared to either the: (i) contralateral limb (within-person comparison); or (ii) uninjured control limb (between-person comparison). We investigated both comparisons, as, while within-person comparisons are more common, the contralateral limb can also be affected by weakness after ACL injury, and comparison to an uninjured control might be more appropriate.

We grouped data by the strength outcome (e.g. hip abduction) and type of comparison (between-person or within-person), and conducted meta-analyses where two or more studies were available.

What did the study find?

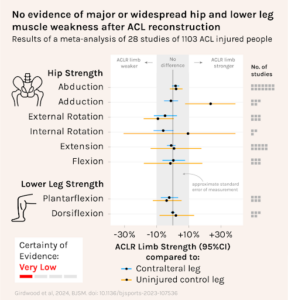

We included 28 studies of 1103 ACL injured people (38% women) and 1145 uninjured controls (81% women). All except one study followed people after ACL reconstruction (ACLR), and most studies looked at strength in the first year post-surgery.

16 studies used a hand-held dynamometer (similar to common methods in clinical practice);12 studies measured strength with an isokinetic dynamometer.

Overall, there was no consistent evidence for major or widespread hip or lower leg muscle weakness:

- Hip abduction strength was most commonly assessed (n=12 studies), with the ACLR limb estimated to be within 5% of the contralateral limb or an uninjured control limb.

- Hip extension strength (i.e. gluteal muscles) was not different within or between people.

- The only major difference identified was for hip adduction strength, where we saw stronger ACL limb strength compared to the contralateral limb, however this result was uncertain from 3 small studies.

Because of the poor quality of the included studies, as well as their observational nature, the certainty of evidence was rated as very low. Despite this, for hip abduction strength it is likely that the results would not change even if new studies were published.

What are the key take-home points?

- Unlike the quadriceps and hamstrings, we did not find significant or widespread weakness in the hip and lower leg muscles in individuals with ACL injury.

- Clinicians should use individualised assessment to guide rehabilitation after ACL injury – target areas of weakness identified on strength tests.

- Most evidence in our review came from the first 6-12 months after ACL reconstruction, and more work is needed to understand whether long-term weakness is a problem.

- Results for some movements, such as hip internal rotation and ankle plantarflexion and dorsiflexion were drawn from only 1-2 studies, so results should be interpreted with caution.

Authors

Michael Girdwood, Adam Culvenor, Brooke Patterson, Melissa Haberfield, Ebonie Rio, Michael Hedger, Kay Crossley

References:

Girdwood M, Culvenor AG, Patterson B, et al. No sign of weakness: a systematic review and meta-analysis of hip and calf muscle strength after anterior cruciate ligament injury. British Journal of Sports Medicine 2024;58:500-510.