The forgotten crystal arthropathy; Metabolically driven or just an incidental finding?

Key words: #MSKplaybook #Chondrocalcinosis #CrystalArthropathy #Pseudogout #CPPD

Introduction

Chondrocalcinosis is a common imaging finding encountered in community MSK clinics. In some patients, it may be considered normal for age, but in others, it can be a sign of a crystal arthropathy (CPPD arthropathy/pseudogout) or be associated with an underlying metabolic, genetic, or medical condition. Early recognition of the condition can help to preserve joint health or alert clinicians to patients that need a full medical and metabolic workup. We discuss the key clinical tests, blood tests and history for MSK clinicians to consider as part of their playbook.

Chondrocalcinosis: incidental finding or evidence of destructive joint disease?

The presence of chondrocalcinosis (deposits of calcium pyrophosphate within joints) increases with age and is often reported on plain radiographs of the hands, wrists, shoulders, ankles, elbows, or hands. For clinicians in a community MSK setting, the question is often if this finding is expected for the patient’s age/medical history or does this need further medical and metabolic workup?

Chondrocalcinosis within joints can go on to cause symptomatic flares of pseudogout or calcium pyrophosphate deposition (CPPD) arthropathy. This is a painful arthropathy, often thought of as the forgotten crystal arthropathy – as in primary care routine imaging X-ray or joint aspiration is not performed to confirm the diagnosis.

Figure 1: Focused clinical history questions In chondrocalcinosis patients

How common is it?

- CPPD has an estimated prevalence of between 4% and 7% in the general population (1,2).

- It is the most common cause of an acutely swollen joint in the elderly, however, it is often overlooked and treated as gout or osteoarthritis.

- Among 100 consecutive patients admitted to an acute geriatric ward, the prevalence of radiological CPP deposition increases with age from 15% for those aged 65-74 to almost 50% for those >84 years (3).

- There is no clear gender predominance (3).

- Early onset chondrocalcinosis is associated with an increased risk of an underlying genetic or metabolic condition at age<50.

| Risk factors for chondrocalcinosis | ||

| Patient-related | Medical/metabolic | Genetic |

| Trauma | Rheumatoid arthritis | Hemochromatosis |

| Osteoarthritis | Gout | Wilsons disease |

| Hyperparathyroidism | Ochronosis syndrome | |

| Loop diuretics | Gitelman’s syndrome | |

| Bisphosphonates | ||

| Hypothyroidism | ||

Table 1: Risk factors for CPPD arthropathy/Pseudogout

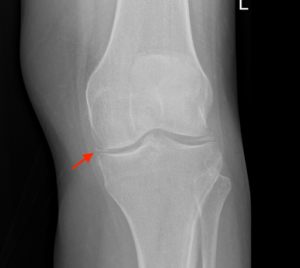

CPPD arthropathy is often diagnosed after imaging has been performed in a symptomatic joint. Diagnostic workups for chondrocalcinosis can vary according to the skills mix and resources available in community MSK clinics, and whether this is done in-house or referred to secondary care. A focussed clinical history and typical X-ray findings (chondrocalcinosis) are usually enough to confirm a suspected diagnosis, but in cases of uncertainty, aspiration of fluid and crystal analysis may be performed (4).

Figure 2: X-ray 1 – Chondrocalcinosis (knee)

Risk factors for CPPD, include medical conditions, metabolic triggers, bone health, or underlying joint disease (osteoarthritis/ rheumatoid arthritis/ gout). Identifying these risk factors and addressing them early can reduce the risk of destruction of joint disease in the long term and can influence the onset and progression of the conditions (5). Age is by far the biggest risk factor and when the condition is present <50 or if there is a family history of hemochromatosis, we recommend further medical workup (Figure 1).

Figure 3: X-ray 2 – chondrocalcinosis (wrist)

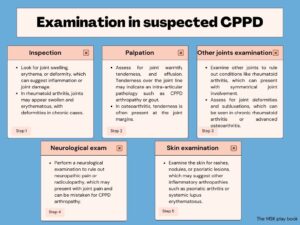

Clinical History

Assessment of an acutely swollen joint, suspicious for calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate disease (CPPD) or pseudogout, should begin with a comprehensive history to screen for relevant risk factors. This includes questions regarding medication history, alcohol, and smoking. The evaluation should continue with a meticulous physical examination, scrutinising not only the affected joint but also other peripheral joints, looking for any signs indicative of more systemic features of rheumatic disease, such as skin or eye involvement, associated with other inflammatory rheumatic diseases. An important distinction to bear in mind during the examination is that, unlike other types of inflammatory arthritis that predominantly affect small joints — such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA) involving metacarpophalangeal joints (MCPJs) and metatarsophalangeal joints (MTPJs), and connective tissue diseases (CTDs) affecting wrists — CPPD/pseudogout tends to impact larger joints. Additionally, gout, another differential diagnosis, typically affects the 1st MTPJ in about 75% of cases.

Figure 4: Focused examination in suspected CPPD patients

Blood Tests

Several blood tests can be considered when investigating underlying, genetic, or medical conditions. These include:

| Blood tests to order | Diagnosis to rule out/in |

| Full Blood Count (FBC)

Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP) |

To evaluate the presence of inflammation and differentiate between inflammatory and non-inflammatory conditions. |

| Urea and Electrolytes | CKD is a risk factor for chondrocalcinosis |

| Bone profile (Calcium, phosphate, and ALP) | If high Calcium: think hyperparathyroidism, or hypocalciuric hypercalcaemia (rare) as a cause of chondrocalcinosis.

If low calcium: chronic kidney disease, and magnesium deficiency should be considered. If low Phosphate and ALP: think about hypophosphatasia (rare) |

| Serum Magnesium | Hypomagnesaemia |

| Thyroid function tests | Hypothyroidism is associated with chondrocalcinosis |

| Parathyroid hormone (PTH) | Hyperparathyroidism can cause chondrocalcinosis. |

| Serum uric acid level | To rule out gout as a cause of the joint pain |

| Iron profile | Hemochromatosis can cause chondrocalcinosis |

Table 2: blood tests to consider in patients with chondrocalcinosis.

These should be focussed based on the clinical and family history of the patient. Community MSK services with direct access to rheumatology should be considered for those with diagnostic uncertainty.

Figure 5: Chondrocalcinosis; a risk factor-based approach of when to consider further investigation.

Treatments

Treatment for CPPD primarily involves addressing acute attacks as well as identifying and managing underlying reversible causes, to prevent future joint damage (7).

- Regular ice packs, relative rest, and aspiration of the joint for symptom relief are often used first line (8). Range of motion exercises should also be included.

- Oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) can be used for acute episodes of CPPD, providing effective relief from pain and inflammation (9).

- Intra-articular corticosteroid injections can also be used for single-joint involvement, often relieving symptoms rapidly (10).

- If CPPD is multi-joint involvement, sometimes oral corticosteroids can be considered, but this is often reserved for more severe diseases.

- Oral colchicine can also be used and is moderately beneficial in both acute attacks and preventing future attacks (8).

- Physiotherapy and strengthening exercises can help to maintain joint function and reduce stiffness.

- Regular physical activity is recommended for patients with chondrocalcinosis.

There are no disease-modifying drugs to treat or prevent CPPD from occurring (8). Importantly, identifying and managing reversible causes, such as metabolic disorders or endocrine abnormalities, are crucial in limiting disease progression and preventing the onset of more widespread arthropathy (11). In the case of genetic causes such as haemochromatosis, onward referral for treatment or genetic counselling may be advised.

Conclusions

- Chondrocalcinosis is a common imaging finding reported in community MSK services.

- The early identification of genetic, metabolic, and medical risk factors can be based on the patient’s age, and a focused clinical history.

- Where risk factors are present, for an underlying reversible cause referral to an MSK service with (rheumatology or musculoskeletal medicine) should be considered.

Authors and Affiliations: Dr Mohammed Subhi, Dr Irfan Ahmed, Dr Imran Lasker, Dr Raj Amarnani, Mr Jack March, Dr Nicholas Shenker

Dr Mohammed Subhi

GP Specialty Registrar

NHS England – East of England

@Moh_irak

Dr Irfan Ahmed

Locum Consultant in Musculoskeletal, Sport & Exercise Medicine

Addenbrookes Hospital

@ExerciseIrfan

Dr Imran Lasker

Consultant Radiologist with Specialist interest in MSK

Mid & South Essex Foundation Trust

@DocLasker

Links to MSK/MRI courses: imranlasker.com, radiologyseminars.com. emergencyimaging.co.uk

Dr Raj Amarnani

Sport and Exercise Medicine Registrar

Barts Health NHS Trust

@DrRajAmar

Mr Jack March

Rheumatology Physiotherapist / Rheumatology Clinical Lead

Chews Health

@physiojack

Dr Ncholas Shenker

Consultant Rheumatologist

Addenbrooke’s Hospital

References:

- Neame RL, Carr AJ, Muir K, Doherty M. UK community prevalence of knee chondrocalcinosis: evidence that correlation with osteoarthritis is through a shared association with osteophyte. Ann Rheum Dis. 2003 Jun;62(6):513-8. doi: 10.1136/ard.62.6.513. PMID: 12759286; PMCID: PMC1754579.

- Felson DT, Naimark A, Anderson J, Kazis L, Castelli W, Meenan RF. The prevalence of knee osteoarthritis in the elderly. The Framingham Osteoarthritis Study. Arthritis Rheum. 1987 Aug;30(8):914-8. doi 10.1002/art.1780300811. PMID: 3632732.

- Rosenthal, A.K. (2023) Clinical manifestations and diagnosis of calcium pyrophosphate crystal deposition (CPPD) disease, UpToDate. Available at: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/clinical-manifestations-and-diagnosis-of-calcium-pyrophosphate-crystal-deposition-cppd-disease?search=prevalence+CPPD+disease&source=search_result&selectedTitle=1~87&usage_type=default&display_rank=1 (Accessed: 13 May 2023).

- Rosenthal AK, Ryan LM. Calcium Pyrophosphate Deposition Disease. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(26):2575-2584.

- Abhishek A, Doherty M. Pathophysiology of articular chondrocalcinosis—the role of ANKH. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2011;7(2):96-104.

- Ryan LM, McCarty DJ. Calcium pyrophosphate crystal deposition disease, pseudogout, and articular chondrocalcinosis. In: Koopman WJ, Moreland LW, eds. Arthritis and Allied Conditions: A Textbook of Rheumatology. 15th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2005:2103-2125.

- Zhang W, Doherty M, Pascual E, et al. EULAR recommendations for calcium pyrophosphate deposition. Part II: management. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70(4):571-575.

- Iqbal SM, Qadir S, Aslam HM, Qadir MA. Updated Treatment for Calcium Pyrophosphate Deposition Disease: An Insight. Cureus. 2019 Jan 7;11(1): e3840. doi: 10.7759/cureus.3840. PMID: 30891381; PMCID: PMC6411330.

- Rosenthal AK, Ryan LM. Calcium Pyrophosphate Deposition Disease. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(26):2575-2584.

- Richette P, Doherty M, Pascual E, et al. 2016 updated EULAR evidence-based recommendations for the management of gout. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76(1):29-42.

- Abhishek A, Doherty M. Pathophysiology of articular chondrocalcinosis–role of ANKH. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2011;7(2):96-104.