In this blog post, we will provide an overview of a recently published study and explain how we leveraged unique data available from the Swedish military conscription register to deepen our understanding of the associations between cardiorespiratory fitness in youth and site-specific cancers in men (1).

Why is this study important?

Cardiorespiratory fitness has well-established associations with several health outcomes, such as cardiovascular disease and mortality. While mortality in cardiovascular disease has decreased over the past four decades due to improved prevention and treatment (2), cancer incidence is predicted to double from 2020 to 2070 (3). Hence, establishing ways of preventing this increase are needed. Obesity is an established risk factor for several types of cancer, and physical inactivity is an established risk factor for some types of cancer. However, there is a lack of evidence on the cancer preventive potential of cardiorespiratory fitness for most site-specific cancers.

How did the study go about this?

We utilized a population-based data set on more than one million 18-year-old Swedish men who underwent compulsory military conscription. The conscription included both objectively assessed cardiorespiratory fitness through a maximal aerobic workload cycle test as well as objectively assessed body weight, blood pressure, and cognitive ability. For a subset of more than 20,000 men it also included information on smoking. The data from the military conscription were merged with data on parental education, emigration status, and cancer diagnoses and causes of death from other national registers with high validity. This allowed us to perform time-to-event analyses of the associations between cardiorespiratory fitness at age 18 and 18 site-specific cancers as well as any cancer. The analyses were adjusted for year, age, and site of military conscription as well as body mass index and parental level of education. The subset of individuals with information on smoking allowed us to assess whether smoking seemed to confound the associations.

What did the study find?

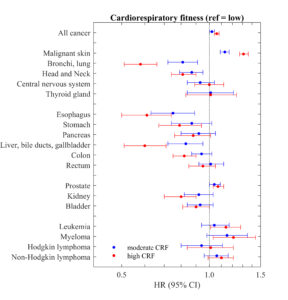

Our study found that higher cardiorespiratory fitness was associated with lower risk of developing cancer in the head and neck, esophagus, stomach, pancreas, liver, colon, rectum, kidney, bladder, and lung. Conversely, higher CRF predicted higher risk of being diagnosed with prostate cancer and malignant skin cancer. The association between fitness and lung cancer seemed to be explained mostly by fit individuals being less prone to smoking, and this also seemed to explain about one third of the associations between fitness and cancer in the esophagus and the liver. The unexpected higher risk of prostate cancer for individuals with high fitness has previously been explained by differences in screening. This might also be the case for skin cancer, while it might also be explained by difference in UV exposure which we couldn’t account for in our analyses.

What are the key take-home points?

Higher cardiorespiratory fitness in youth was associated with lower risk of developing ten of the site-specific cancers included in our analyses, with several of these being in the gastrointestinal tract. The risk was approximately 20% lower for several of these for men with high versus low cardiorespiratory fitness. With the expected increase in cancer incidence, this should serve as yet another call for clinicians to promote physical activity to increase cardiorespiratory fitness of their patients. This should also further strengthen the incentive for policymakers to promote public health work focused on improving cardiorespiratory fitness in youth.

Author information

Aron Onerup, aron.onerup@gu.se

References

- , et al.

- Mensah GA, Wei GS, Sorlie PD, et al. Circ Res 2017;120(2):366-80

- Soerjomataram I, Bray F. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2021;18(10):663-72.