Keywords: rest, exercise, sport-related concussion

In this blog, we summarize our recent publication that presents evidence regarding the risks and benefits of physical activity (PA), prescribed aerobic exercise treatment, rest, cognitive activity, and sleep during the early recovery phase after sport-related concussion (SRC) (1). This systematic review was developed for the international Concussion in Sport Group (CISG) Consensus Conference held in 2022 in Amsterdam, the Netherlands.

Why is this study important?

Concussion is a public health problem with millions of children and young adults sustaining SRC every year. While most athletes recover within weeks, a significant minority (one third) remains persistently symptomatic beyond 1 month, which impairs school performance, return to sport, and quality of life. The traditional approach to concussion management, based largely on expert opinion, was strict cognitive and physical rest until the acute symptoms resolved. Emerging evidence, however, has challenged the “rest is best” approach (2).

How did the study go about this?

We systematically searched the published literature since 2001 for the strongest evidence regarding the effects of PA/prescribed exercise, rest, cognitive activity, and sleep on recovery during the first 2 weeks after SRC (Figure 1). Based upon study quality (mostly randomized trials- the highest level of evidence for a medical intervention), we performed a meta-analysis (a statistical method that combines the results of multiple scientific studies) for the effect of PA/prescribed exercise on SRC recovery. We performed a narrative synthesis (a description of the data) for the effects of rest, cognitive activity, and sleep.

Figure 1: Modified Preferred Reporting Item for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA)

What did the study find?

The best evidence confirms that strict physical and cognitive rest until all symptoms are gone (colloquially called “cocooning”) is not effective for SRC. An important finding is, contrary to the fear that any increase in symptoms after SRC harmed the brain and delayed recovery, mild symptom increase (defined as no more than a 2-point symptom increase during physical or cognitive activity when compared with the pre-activity level on a 0-10 scale) does not impair recovery. We also found that light intensity PA (e.g., walking that does not more than mildly exacerbate symptoms) during the first 48 hours after SRC facilitates recovery. Moreover, a prescription for sub-symptom threshold aerobic exercise treatment, based upon systematic exercise testing that identifies each person’s more-than-mild symptom exacerbation heart rate threshold, can safely be started within 2-14 days of SRC. Aerobic exercise as “medicine” early after SRC both facilitates recovery and, importantly, reduces the incidence of symptoms persisting beyond one month. Sleep disturbance appears to impair SRC recovery whereas reducing typical time spent viewing screens (e.g., phones, computers) during the first 48 hours after injury appears to facilitate recovery.

What are the key take-home points?

The treatment approach to SRC has changed radically and the below points summarize the findings from this study.

- Adolescents and young adults should not “cocoon”.

- They may return to light PA (e.g., walking and easy activities of daily living) during the first 48 hours after SRC.

- They should limit their typical screen use within the first 48 hours after injury to facilitate recovery.

- Good sleep is important.

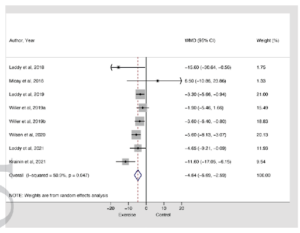

- Individualized aerobic exercise treatment (based upon formal exercise testing) can be prescribed to athletes as soon as 2 days after SRC. Early exercise “medicine” facilitates recovery on average by 5 days (range 2.5-7 days, Figure 2) when compared with not using exercise to treat SRC. This personalized approach significantly reduces the incidence of symptoms persisting beyond one month and has even been shown to promote recovery in athletes who continue to experience symptoms beyond one month.

- Athletes experiencing more-than- mild symptom exacerbation should stop physical or cognitive activity and rest until the exacerbation subsides. More-than-mild concussion symptom exacerbation is typically brief, does not delay recovery, and should not prevent athletes from resuming activity/exercise after a brief period of relative rest.

Figure 2: Forest plot depicting the impact of physical activity and prescribed exercise on recovery compared with a control group.

References:

- Leddy JJ, Burma JS, Toomey CM, et alRest and exercise early after sport-related concussion: a systematic review and meta-analysisBritish Journal of Sports Medicine 2023;57:762-770.

- McCrory, P., Meeuwisse, W., Aubry, M., et al. Consensus Statement on Concussion in Sport-The 4th International Conference on Concussion in Sport Held in Zurich, November 2012. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 47, 250-258. 2013.

Authors: Blog by Dr John Leddy