Authors: Bryant Webber; Heather Yun; Geoffrey Whitfield

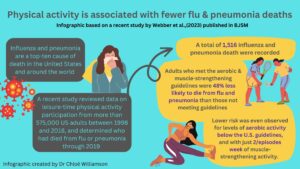

After reviewing 25 studies during the pandemic, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention concluded that being physically inactive increases the chance of severe COVID-19 illness. Given emerging interest in the relationship between physical activity and infectious diseases, we explored the impact of types and amounts of physical activity on influenza and pneumonia deaths. Analyzed collectively (as they often are in vital statistics systems), influenza and pneumonia are a top-ten cause of death in the United States and around the world. This blog provides an overview of our recently published review.

Why is this study important?

Guidelines from the United States and World Health Organization recommend physical activity for a variety of physical and mental health benefits. Released respectively in 2018 and 2020, these guidelines do not include infectious disease control as a benefit. Our study (recently published in BJSM) provides compelling evidence that regular leisure-time physical activity can lower the risk of dying from influenza or pneumonia.

The evidence is compelling because it is based on a large and nationally representative sample, for whom we had baseline physical activity information and up to 22 years of follow-up data. Our findings may be valuable for health care providers and their patients as they search for additional actions, beyond vaccination, to protect themselves against influenza and pneumonia.

How did the study collect physical activity and death data?

We reviewed data on leisure-time physical activity participation from more than 575,000 U.S. adults who participated in the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) between 1998 and 2018. We categorized adults as meeting the guidelines if they reported at least 150 min/week of moderate-intensity aerobic activity and at least 2 episodes/week of muscle-strengthening activity. We also categorized them into five levels of moderate-intensity aerobic physical activity (<10, 10–149, 150–300, 301–600, and >600 min/week) and five levels of muscle-strengthening activity (<2, 2, 3, 4–6, and ≥7 episodes/week).

Using the National Death Index, we determined who had died from influenza or pneumonia through 2019. We then assessed the risk of influenza and pneumonia death by different levels of physical activity, controlling for other factors that may have increased or reduced this risk, such as demographics, smoking and alcohol habits, body mass index, vaccination status, and health conditions (such as heart disease and asthma).

What did the study find?

A total of 1,516 influenza and pneumonia deaths were recorded among study participants. Adults who reported meeting the aerobic and muscle-strengthening physical activity guidelines were 48% less likely to die from influenza and pneumonia compared to those who reported not meeting the guidelines. We also found that any level of aerobic physical activity, even at amounts below the recommended level, lowered the risk of death from these causes compared to no aerobic activity. For muscle-strengthening activity, adults who performed 2 episodes/week had a 47% lower risk of death from influenza or pneumonia than those who performed fewer than 2 episodes/week. In contrast, risk was 41% higher among adults reporting very high levels of muscle-strengthening activity (7 or more episodes/week).

What are the key take-home points?

Regular physical activity may reduce the risk of death from influenza and pneumonia. Lower risk is seen even with low levels of aerobic physical activity (at least 10 min/week) and with just 2 episodes/week of muscle-strengthening activity. Health care providers may wish to screen all their patients for physical activity and promote aerobic and muscle-strengthening activity among those who are inactive.

In the bigger picture, this study adds to the growing body of science showing that physical activity is not just valuable for preventing chronic diseases, such as heart disease and cancer. It may even have a role in preventing death from influenza and pneumonia.