Keywords = ACL, concussion, neuromuscular control

In the world of sports, soccer is unique because of the purposeful use of the unprotected head for controlling and advancing the ball. This skill places the player at risk of head injury. Head injury can be a result of contact of the head with another player’s head (or other body parts), ground, goal post, or the ball. Such impacts can lead to contusions, fractures, eye injuries, concussions, or rarely, death. Coaches, players, parents and physicians are rightly concerned about the risk of head injury in soccer. Current research shows that selected retired soccer players have some degree of cognitive dysfunction (1). It is important to determine the reasons behind such outcomes. Heading the ball has generally been blamed. However, a closer look at studies focusing on heading has revealed methodological concerns that question the validity of blaming purposeful ball heading for neurocognitive and lower limb chain reaction injuries.

This blog will discuss if there is a connection between mild traumatic brain injury (TBI)/concussion and neuromuscular control at the lower limb in football players and summarises our 2021 paper (2).

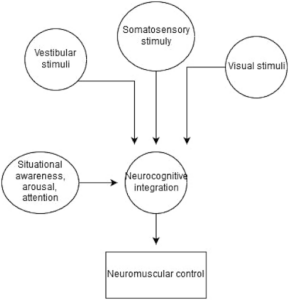

Figure 1 taken from Kakavas et al., 2020 (3)

Mild TBI and ball heading:

It is unlikely that the subconcussive impact of purposeful heading causes the observed negative outcomes noted in Figure 1. However, it is not known whether multiple concussive impacts may have lingering effects (2). In addition, it is unknown whether the noted deficits have any effect on daily life.

Soccer accounts for a significant number of sub-concussive episodes in sports. Excessive heading of the ball (more than 1,000 episodes per year) may cause subclinical brain injury, the effects of which are not as well defined as those of recognized frank concussion. However, most published studies have focused on collegiate and professional players when most soccer players are amateur recreational league players .

Heading with the unprotected head to direct the ball during game play is increasingly recognized as a major source of exposure to concussive and sub-concussive repetitive head impacts. These impacts have been linked to changes in brain structure visible on neuroimaging, and decreased performance on cognitive tasks both with short term and long-term exposure.

Concussion involves several clinical domains: symptoms, physical signs, behavioral changes, cognitive impairment, and sleep disturbance. The physical signs of concussion can resolve quickly, but some players may manifest persistent impairment.

The Union of European Football Associations (UEFA) first published a call for research proposals in May 2017, in which potential researchers were asked to address 3 questions.

- What is the burden of heading in youth football?

- Are there differences in the way headers are taught in football training?

- Are there differences in the incidence and characteristics of football headers in matches and training, amongst different age and gender categories?

The new heading guidelines are published from UEFA in June 2020 with aim to protect the health of the young footballers.

Sub-concussion effects in the neuromuscular control of the knee:

When the lower limb lacks neuromuscular control the most devastating injury is anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) rupture. When the stresses to which the ACL is exposed exceed its mechanical properties, but extreme knee loading scenarios may be potentiated through abnormal neuromuscular control in the lower limb, with gender differences in hip rotation and rear foot pronation in the transverse and frontal planes. Concussion can also result in decreased postural stability from impairment on the afferent signals from the cervical spine, the vestibular-ocular system, and the visual systems. Persistent sensorimotor impairment after resolution of concussion symptoms would likely contribute to an increased injury risk, and further studies are warranted. These neurocognitive impairments are likely linked with neuromuscular control, motor learning, and other aspects critical for the performance and safety of the athlete.

From a sports traumatology and rehabilitation perspective, we should try and produce interventions first which allow us to assess neurocognitive performance and identify athletes at risk for injury. Also, in the rehabilitation process, neuromuscular training tools should incorporate progressively more challenging tasks. The benefits of using tasks such as dual-attention during clinical assessment are currently being explored when assessing and managing concussion . This strategy can be successfully translated to ACL injury risk screening, and neurocognitive strategies may be employed in ACL injury prevention and ACL injury rehabilitation. Sport activities demand initiating and maintaining appropriate performance of dynamic activities in a complex, rapidly changing environment (3). The success of each action is contingent on voluntary and in-voluntary motor commands modulated by sensory processing, attention, and motor planning.

Take home messages:

Neuroscience will continue to help uncover how the nervous system influences and determines motor control, and the mechanistic errors in motor control resulting in non-contact ACL injury. Poor baseline neurocognitive performance or impairments in neuro- cognitive performance via sleep deprivation, psychological stress, or concussion injury can increase the risk for subsequent musculoskeletal injury. Head injury prevention programs can help athletes beyond ACL injury, and their impact will extend to prevention of impairment of neural function and neurocognition.

Authors: Georgios Kakavas PT OMT ATC MSc.PhDc.

References:

- Didehbani N, Fields LM, Wilmoth K, LoBue C, Hart J, Cullum CM. Mild Cognitive Impairment in Retired Professional Football Players With a History of Mild Traumatic Brain Injury: A Pilot Investigation. Cogn Behav Neurol. 2020 Sep;33(3):208-217

- Kakavas, G., Malliaropoulos, N., Blach, W. et al. Ball heading and subclinical concussion in soccer as a risk factor for anterior cruciate ligament injury. J Orthop Surg Res 16, 566 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13018-021-02711-z

- Kakavas G, Malliaropoulos N, Pruna R, Traster D, Bikos G, Maffulli N. Neuroplasticity and Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury. Indian J Orthop. 2020 Jan 31;54(3):275-280