By Chloë Williamson and Jennifer Duncan

Busy schedules, family commitments, fatigue, dark evenings and slippy pavements are just some of the various factors that can make convincing the general public to be physically active even more challenging. One way we can influence attitudes, motivation and intention to be active is through physical activity messaging and communication. Though messaging can be a helpful tool in physical activity promotion, it also has the potential to be harmful if we don’t base our messages on evidence. So, how can we best use messaging to promote physical activity?

Physical activity messages to date have largely focused on long-term prevention of disease and premature mortality, despite there being a lack of theory or evidence to support this approach. In a previous blog, we discussed the role of messaging in improving population physical activity levels. Notably, we highlighted the idea that what is important to us (as healthcare professionals, policymakers and researchers in the field of public health), is not necessarily what is important to the general public. Of course, many individuals may value their long term health and may be interested in reducing their risk of non-communicable disease later in life. But is this the most effective way to change how people feel and act relating to physical activity in the short-term?

Findings from our review of physical activity messaging identified that messages should highlight the benefits of physical activity (rather than the consequences of inactivity). Specifically, evidence from this review supports the communication of shorter term benefits. Following this scoping review, we developed the Physical Activity Messaging Framework, and have since applied this in a proof-of-concept study to explore messaging preferences in a specific population subgroup. Our ongoing research, alongside other research in this field, is increasingly supporting the promotion of short-term benefits of physical activity (which largely relate to mental and social health). This approach, in line with behavioural science and social marketing, would see messages that convey what people can gain from being physically active almost immediately, as opposed to what benefits they may reap years later.

Physical activity messages often do not align with this growing body of evidence, including those that have been put out during the festive period. For example, on the 21st of December 2021, the World Health Organization tweeted the following PA message: “Insufficient physical inactivity puts you at risk of noncommunicable disease such as cardiovascular diseases, cancer and diabetes. This holiday season, move more!”. This type of message is not in line with key messaging evidence. It highlights physical inactivity consequences (rather than benefits of physical activity), and focuses on long-term physical health outcomes (rather than short term mental health and social benefits). Furthermore, the Physical Activity Messaging Framework highlights the importance of considering context and what is important to the target audience at that time. It is quite possible that risk of cardiovascular disease, cancer and diabetes are not the most important considerations for the general public over the holiday season. Perhaps they would instead value benefits such as spending time with loved ones and reducing feelings of stress. Therefore, there is a need to change our approach to physical activity messaging.

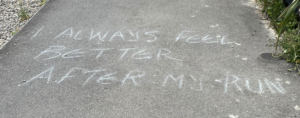

Promisingly, some good examples of messages do exist. The figure below shows a message spotted very recently by one of the BJSM blog authors on their local running path that says “I always feel better after my run”.

We want to contribute to seeing more of these good example messages. As part of our ongoing physical activity communication research at the University of Edinburgh, we have developed some initial key evidence-based messages for use during the festive period (and beyond).

We hope that this blog and the messages in the infographic can help you to help others ‘step’ into Christmas!