‘Clinical Take Home Messages’ from an OPTIKNEE systematic review

This blog is part of a series on work by OPTIKNEE Consensus. This is an international consensus group focused on improving knee health and preventing osteoarthritis after a traumatic knee injury.

People who injure their knee have an elevated risk for post-traumatic knee osteoarthritis (PTOA) (1). The international OPTIKNEE consensus aims to guide rehabilitation to optimise knee health and prevent knee PTOA. As part of this consensus, we recently published a systematic review in BJSM (OPEN ACCESS) to identify risk factors for osteoarthritis after knee injury (2).

Why is this study important?

Knee PTOA is associated with a young age of onset (twenties-to-forties). Therefore, people with knee PTOA experience progressive joint pain (3) disability, and reduced quality-of-life (4) for much of their adult life (5, 6). Because PTOA is incurable, prevention is key (7). But who should clinicians target, and what should we do? Studies designed to identify risk factors, including randomized – controlled trials (RCTs) and cohort studies, might provide clues. Systematic reviews combine the findings from several studies, providing high-level evidence.

What did we do?

Our review included RCTs and cohort studies that assessed potential risk factors for symptomatic or structural osteoarthritis in people with a knee injury. We searched five databases for eligible studies, assessed risk-of-bias, performed quantitative (meta-analysis) and semi-quantitative syntheses, and reached a conclusion and level of evidence for each potential risk factor. We separated symptomatic and structural osteoarthritis because symptoms interfere with people’s lives motivating them to seek health care, while structural osteoarthritis can exist without symptoms.

What did the study find?

We identified 81 potential risk factors across 66 studies including approximately 800,000 people. The clinical value of 80% of the potential risk factors was unclear because they were only assessed in one study. Structured syntheses of the remaining factors, revealed information about who is at risk (unmodifiable risk factor) of knee PTOA, and how to reduce the risk (modifiable risk factors).

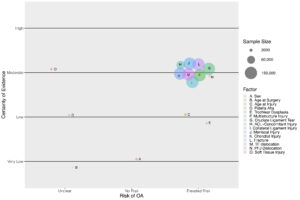

Figure 1 summarizes what we learned about who is at risk of symptomatic knee PTOA. The strongest level of evidence (moderate-certainty) suggests that many knee injury types increase risk, with the greatest risk seen after ACL and/or meniscus tears, multi-structure injuries, or dislocations (patello and tibiofemoral). There is also low-certainty evidence that older injury age may increase risk.

Figure 1: Non-modifiable risk factors for symptomatic knee PTOA

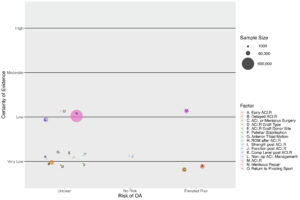

Figure 2 summarizes what we learned about how to reduce symptomatic knee PTOA risk. The strongest evidence (low-certainty) suggests that ACL reconstruction (ACLR; versus no ACLR) may increase risk, while the influence of meniscal repair (versus partial menisectomy) and return-to-pivoting sport is unclear. There is also very-low certainty evidence that early ACLR (versus delayed) may increase risk.

Figure 2: Modifiable risk factors for symptomatic knee PTOA

What are the key take-home messages?

Our findings challenge popular beliefs about who is at elevated risk for knee PTOA and provide a foundation for learning about how to reduce it.

1- People with ALL types of knee joint injuries – NOT just those who experience an ACL and/or meniscal tear – have an elevated risk for knee PTOA.

2 – A lack of evidence about how to prevent knee PTOA should NOT STOP clinicians from supporting patients to manage their knee health after an injury. Treatment targets include known risk factors for knee osteoarthritis in general (physical inactivity, quadriceps weakness, unhealthy body fat) with a focus on education, weight-bearing physical activity, and muscle strengthening exercises.

3 – Our findings can help to MANAGE EXPECTATIONS about things commonly believed to protect against or increase risk for PTOA, where evidence suggests otherwise. For example, the perceived value of early ACLR for reducing PTOA risk, and harmful effect of returning-to-pivoting sports.

4 – KNOWLEDGE GAPS about how to reduce knee PTOA risk can be addressed when patients, clinicians and researchers work together across disciplines and institutions, to overcome the challenges of conducting rigorous studies.

References:

- Snoeker B, Turkiewicz A, Magnusson K, et al. Risk of knee osteoarthritis after different types of knee injuries in young adults: a population-based cohort study. Br J Sports Med 2020;54(12):725-30. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2019-100959 [published Online First: 2019/12/13]

- Whittaker JL, Losciale JM, Juhl CB, et al. Risk factors for knee osteoarthritis after traumatic knee injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials and cohort studies for the OPTIKNEE Consensus. Br J Sports Med 2022;Published Online First September 2, 2022 doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2022-105496

- King LK, Kendzerska T, Waugh EJ, et al. Impact of Osteoarthritis on Difficulty Walking: A Population-Based Study. Arthritis care & research 2018;70(1):71-79. doi: 10.1002/acr.23250 [published Online First: 2017/05/18]

- Abbott JH, Usiskin IM, Wilson R, et al. The quality-of-life burden of knee osteoarthritis in New Zealand adults: A model-based evaluation. PLoS One 2017;12(10):e0185676. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0185676 [published Online First: 2017/10/25]

- Leyland KM, Gates LS, Sanchez-Santos MT, et al. Knee osteoarthritis and time-to all-cause mortality in six community-based cohorts: an international meta-analysis of individual participant-level data. Aging Clin Exp Res 2021 doi: 10.1007/s40520-020-01762-2 [published Online First: 2021/02/17]

- Ajuied A, Wong F, Smith C, et al. Anterior cruciate ligament injury and radiologic progression of knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Sports Med 2014;42(9):2242-52. doi: 10.1177/0363546513508376

- Whittaker JL, Runhaar J, Bierma-Zeinstra S, et al. A lifespan approach to osteoarthritis prevention. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2021;29(12):1638-53. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2021.06.015 [published Online First: 2021/09/25]

Authors:

Justin M. Losciale (1&2)

Alison Hoens (1&2)

Jackie L. Whittaker (1&2)

Affiliations:

(1)Department of Physical Therapy, Faculty of Medicine, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada

(2)Arthritis Research Canada, Vancouver, Canada

Twitter:

ORCID:

Justin M. Losciale 0000-0001-5135-1191

Alison Hoens 0000-0002-9533-9079

Jackie L. Whittaker 0000-0002-6591-4976