Keywords: gender bias, sports medicine physician, sexual harassment

This blog provides highlights of a recent paper regarding gender bias in sports medicine (1).

Recently, physician researchers from Japan and the United States worked together to gain a better understanding of gender bias in sports medicine. Similar to previous findings, it was noted that there is a difference in how female sports medicine physicians are treated compared to their male counterparts. Based on the results, sports medicine societies and sporting organizations should develop and implement policies around diversity and inclusion, bullying, harassment, and all forms of discrimination. Annual data should also be collected on these across sport to ensure organizations move toward gender equality and safer work environments for physicians of all genders, races, ethnicities and sexual orientations.

Why is this study important?

Sports medicine operates in a unique environment. Physicians are required to communicate not only with athletes, but also with coaches, athletic trainers (ATs), and other professions that surround the athlete.

The presence of gender bias could lead to more stress, lower job satisfaction, and higher burnout rates of female Sports Medicine Physicians (SMPs). In order to achieve gender equity in the sports medicine world, we must first evaluate the environment to identify areas that need to be addressed.

How did the study go about this?

A survey was sent around the world and the responses from 1193 SMPs from 51 countries were analyzed. They were asked how often they felt disrespected or had their judgement questioned by key stakeholders within athletics as well as how often they were sexually harassed. The authors then looked at the responses to see if there were different answers between male and female sports medicine physicians.

What did the study find?

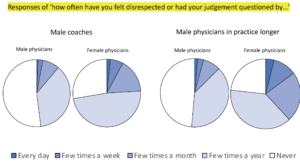

We found that female SMPs felt disrespected or had their judgment questioned more than male SMPs. This was the case for almost all of the categories studied including their interactions with male athletes, female athletes, male coaches, female coaches, male athletic trainers, female athletic trainers, administration, male physicians of all ages, and female physicians in practice longer than them. The only category where male and female SMPs did not differ in feeling disrespected was in their exchanges with female physicians in practice the same or less time as them. Sports medicine physicians in Asia perceived less disrespect or had their judgment questioned less compared to European sports medicine physicians. Additionally, female North American physicians perceived disrespect or had their judgment questioned more than their female European counterparts.

Female SMPs reported higher rates of sexual harassment than male counterparts by the following groups: male athletes, male coaches, male physicians in practice both longer and shorter than them, male athletic trainers, and administration. In the survey, 29.9% of female SMPs reported being sexually harassed by male physicians in practice longer than them and 18.4% were sexually harassed by male athletes.

Details of the responses of ‘how often have you felt disrespected or had your judgment questioned by the following?’ on both male and female sports medicine physicians.

What are the key take-home points?

We hope this study creates more awareness about the disrespect, harassment, and inequity experienced by women in sports medicine. While all members of the sports environment (athletes, coaches, athletic trainers) should work together and treat each other with respect, the experiences reported by women in this study reveal a toxic work culture that is extremely pervasive and disturbing. We challenge the sports medicine community to examine current practices and offer solutions to make the workplace a safer environment for both men and women across the world.

Authors

Yuka Tsukahara (Associate editor of BJSM),1 Melissa Novak,2 Seira Takei,3 Irfan M Asif,4 Fumihiro Yamasawa,5 Suguru Torii,6 Takao Akama,6Hideo Matsumoto,7 Carly Day8,9

1Waseda Institute for Sport Sciences, Waseda University

2Family Medicine, Oregon Health and Science University

3Waseda Institute of Human Growth and Development, Waseda University,

4Department of Family and Community Medicine, The University of Alabama at Birmingham School of Medicine

5Marubeni Health Promotion Center

6Faculty of Sport Sciences, Waseda University

7Japan Sports Medicine Foundation

8Department of Health and Kinesiology, Purdue University

9Sports Medicine, Franciscan Physician Network

References

- Tsukahara Y, Novak M, Takei S, Asif IM, Yamasawa F, Torii S, et al. Gender bias in sports medicine: an international assessment of sports medicine physicians’ perceptions of their interactions with athletes, coaches, athletic trainers and other physicians. Br J Sports Med. 2022.

- McCurry J. Two more Japanese medical schools admit discriminating against women 2018. Available: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/dec/12/two-morejapanese-medical-schools-admit-discriminating-against-women

- Frank E, Brogan D, Schiffman M. Prevalence and correlates of harassment among US women physicians. Arch Intern Med 1998;158:352–8.

- García-González J, Forcén P, Jimenez-Sanchez M. Men and women differ in their perception of gender bias in research institutions. PLoS One 2019;14:e0225763.

- Lewis C, Jin Y, Day C. Distribution of men and women among NCAA head team physicians, head athletic trainers, and assistant athletic trainers. JAMA Intern Med 2020;180:324–6.

- The World Economic Forum. Global gender gap report, 2020. Available: https://www.weforum.org/reports/gender-gap-2020-report-100-years-pay-equality