When to stand down injured athletes, and when to let them push through.

Less than 48 hours before boarding our flight to Iceland for the 2020 Ice Hockey World Cup, a worst-case scenario occurred for New Zealand’s women’s ice hockey team. A star player went down on the ice and felt the pop as her ACL ruptured. Exactly two weeks later this player top scored in the first game of the World Cup and then was awarded most valuable player along with a bronze medal in the fifth and final game of the series.

The exception to the rule.

No swelling. No pain. No concurrent injury. Strong muscles from intensive pre-season. Functional testing symmetrical. Fantastic neuromuscular control. Yet later that evening the knee gave way. The next morning an MRI confirmed an isolated ACL rupture with minimal bony bruising. A discussion was had with the player, coach and management regarding the risks associated with playing on a freshly ruptured ACL and the team’s options. It was too late for flights to be refunded. New Zealand’s players pay their own way to the World Cup and the player was adamant that she would play if the knee allowed. As the team’s physiotherapist and only medic my options were either ‘no’, or ‘let’s see how it looks over the next two weeks’. With extensive informed consent I sourced and fitted an ACL brace. We would monitor and see.

Playing elite level pivoting sport while ACL-deficient

Risks of early return to play post ACL rupture include acute secondary injuries such as meniscal and chondral injuries, as well as long-term consequences including post-traumatic osteoarthritis and joint replacements [1][2]. With these risks acknowledged and my recommendation against it, the player chose to participate in the World Cup. Once this decision to play was made, harm minimisation was the key goal of physiotherapy. Tape. Maintaining strength. High level proprioception. Despite these safeguards, twice during the tournament the athlete went down hard and I second guessed my decision, heart in mouth. Each time the brace and copious strapping did their job. She made it through the five games in Iceland without major issue and when eventually she had the ACL reconstructed, there still was only the isolated ACL rupture.

Reflecting on duty of care and ethics.

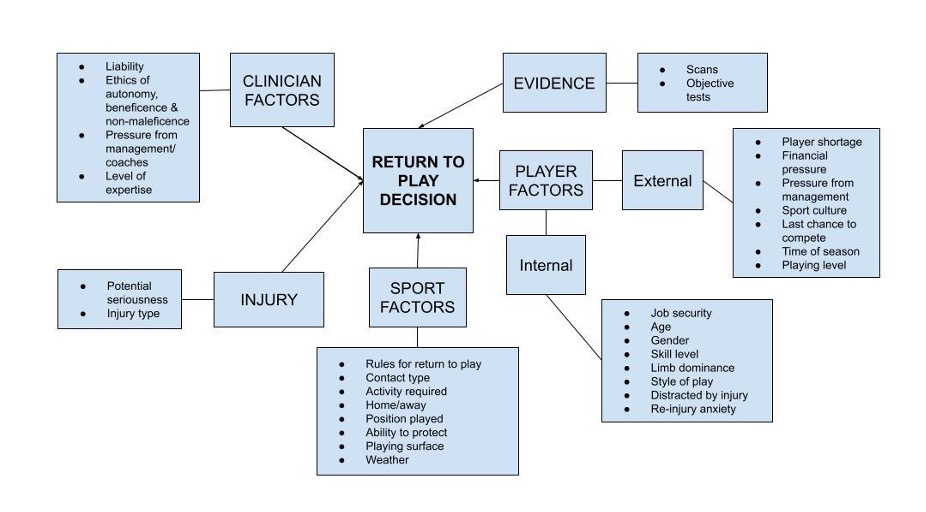

Several days before the ACL rupture, I stood down two other players due to unresolved concussions. The decision for them to sit out was made easily and was non-negotiable. So why was the ACL treated differently? The player was informed of the risks and collaborative decision making was used, yet I would not afford the same consideration to a player with a head injury. Figure 1 reflects a summary of the subconscious elements that impacted this decision making, adapted from [3] and [4]. Of all the factors below, the biggest impact on my decision came from the ethical principles of beneficence, nonmaleficence and autonomy.

Figure 1. Elements influencing decision making in the context of return to play

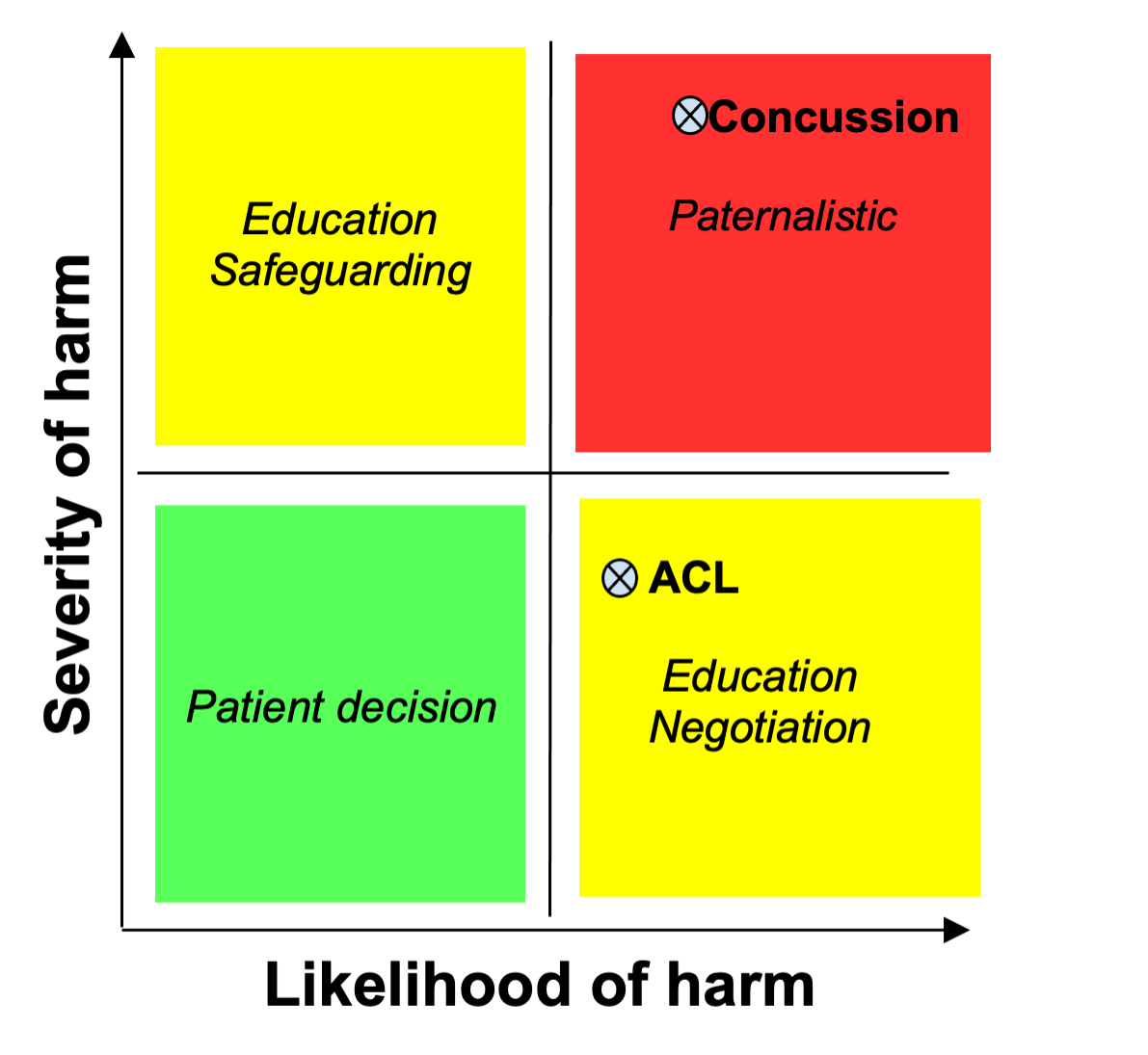

The application of the ethical principle of nonmaleficence is demonstrated in Figure 2, adapted from [5], with an analysis of potential seriousness of harm of early return to play. My interpretation of where ACL rupture and concussion fall on the scale can be seen. The worst-case scenarios fall in different categories and as such required different approaches. Although a collaborative decision-making process is preferred, in situations where there is high risk of severe injury a practitioner-led or paternalistic approach can be required [6].

Figure 2. Application of ethical principles of nonmaleficence (adapted from [5])

As health professionals working with teams we hold responsibility for our players’ safety. The ethics of return to play decisions should be carefully considered before a decision is made. Visual aids such as those presented here can assist with difficult decision making.

Author:

Michelle Jane Novotny,

Physiotherapist, Wanaka Physiotherapy and New Zealand Ice Fernz

BPT, completed towards the Sports Physiotherapy paper (PGCertPhty), University of Otago, New Zealand

References

- Sanders TL, Kremers HM, Bryan AJ, Fruth KM, Larson DR, Pareek A, Levy BA, Stuart MJ, Dahm DL, Krych AJ. Is anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction effective in preventing secondary meniscal tears and osteoarthritis? Am J Sports Med 2016;44(7):1699-707. doi: 10.1177/0363546516634325

- Sommerfeldt M, Goodine T, Raheem A, Whittaker J, Otto D. Relationship Between Time to ACL Reconstruction and Presence of Adverse Changes in the Knee at the Time of Reconstruction. Orthop J Sports Med. 2018 ;6(12):2325967118813917. doi:10.1177/2325967118813917

- Ardern CL, Bizzini M, Bahr R. It is time for consensus on return to play after injury: five key questions. Br J Sports Med. 2016;50(9):506-508. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2015-095475

- Creighton DW, Shrier I, Shultz R, Meeuwisse WH, Matheson GO. Return-to-play in sport: a decision-based model. Clin J Sport Med. 2010;20(5):379-85. doi:10.1097/JSM.0b013e3181f3c0fe

- Anderson L. Doctoring risk: Responding to risk-taking in athletes. Sport, Ethics and Philosophy. 2007;1(2):119-134. doi:10.1080/17511320701425090

- Thompson J, Gabriel L, Yoward, S. and Dawson, P. The advanced practitioners’ perspective. Exploring the decision-making process between musculoskeletal advanced practitioners and their patients: An interpretive phenomenological study. Musculoskeletal Care. 2021 May;1-9. doi:10.1002/msc.1562