Part 1 of a 2-part blog series.

A road cyclist in his forties has to brake suddenly to avoid a collision when a car pulls out abruptly, throwing him over the bicycle handlebars. He decides to seek medical advice and is diagnosed with a Morel-Lavallee lesion.

A Morel-Lavallee lesion (MLL) is a closed degloving injury that occurs where skin and superficial fascia get separated from the deep fascia, creating a potential space. This was first described by a French surgeon, Maurice Morel-Lavallee, in 1853, hence the eponymous name. (1)

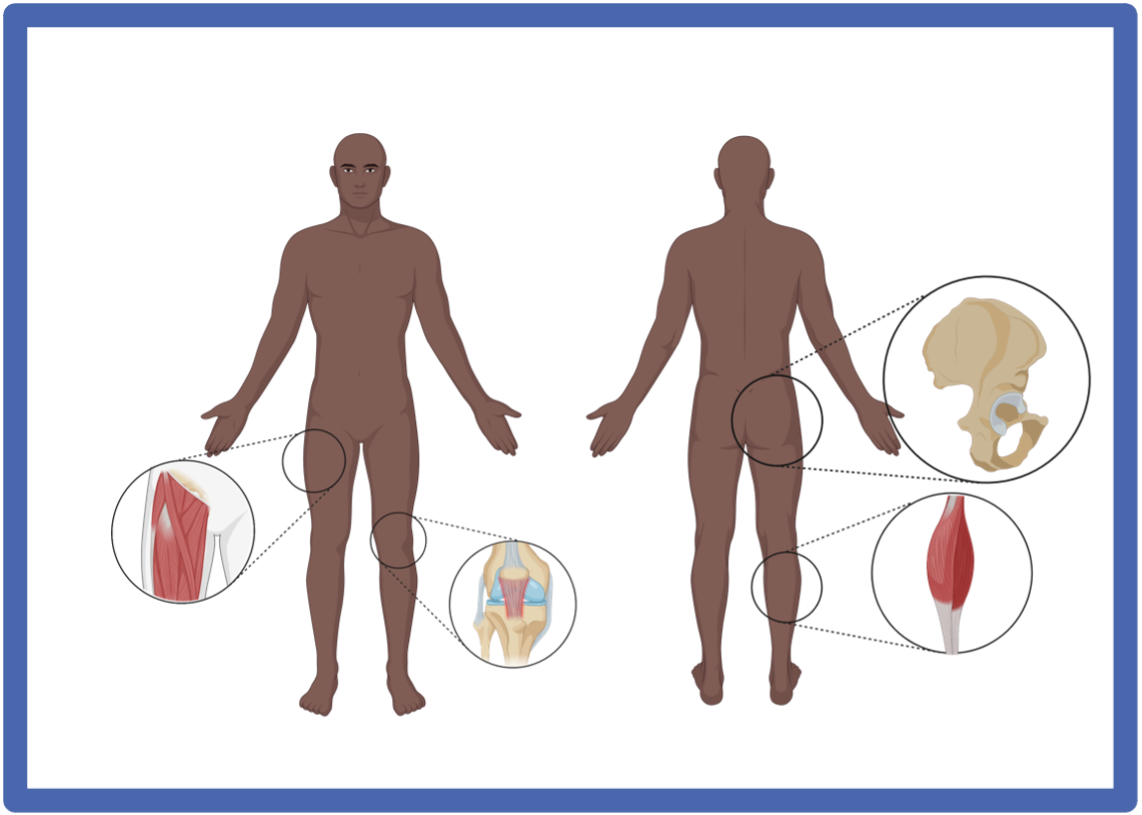

Anatomy

The greater trochanter (lateral hip) is the most commonly affected region for a MLL to occur, owing to a combination of the superficial position of the femoral cortex, relative mobility of the subdermal soft tissues, and strength of the underlying tensor fascia lata. (1) MLL can also occur in the thigh, pelvis, knee, gluteal region, lumbosacral area, abdominal area, and calf/ lower leg. (4)

Aetiology

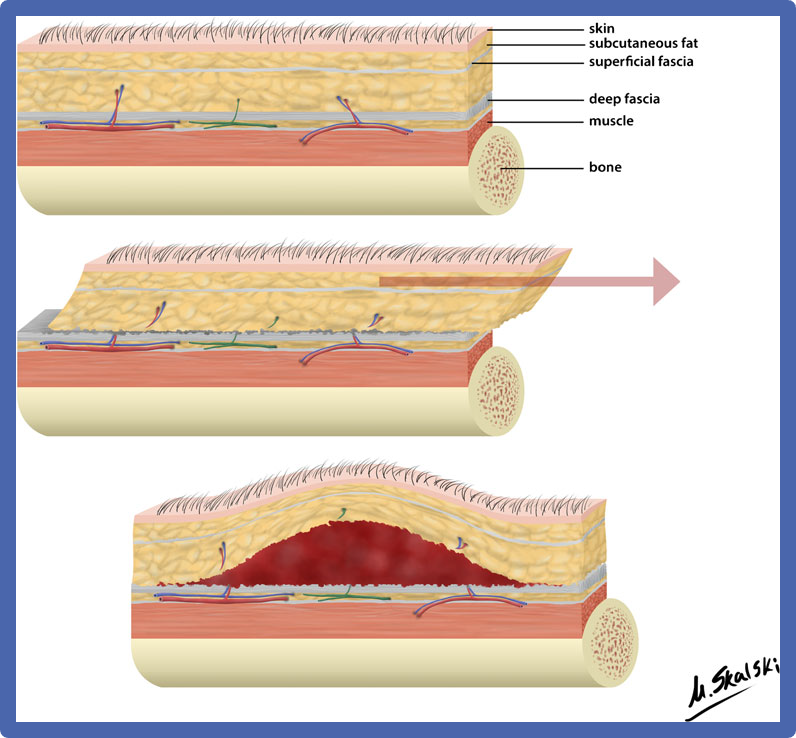

The initial shearing insult between the fascial layers disrupts the soft-tissue envelope’s perforating vascular and lymphatic structures, resulting in a characteristic haemolymphatic fluid collection. Inflammatory and metabolic products within this fluid stimulate cellular permeability and further leakage from the vessels and lymphatics into the created space. (3) As time progress, a capsulated lesion develops, which is lined by a fibrous capsule. The lesion is filled with blood products, necrotic fatty tissue, debris, and fibrin. (2)

Lesion evolution is divided into four stages. (i) The dermis is separated from the underlying fascia in the first stage. (ii) Exsanguination from the lymphatics and vasculature from the injured subdermal plexus subsequently produces a fluid collection mixture of blood, lymph, and fatty debris. (iii) Over time, these components become replaced by serosanguinous fluid as the lesion enlarges. (iv) If left untreated during the acute stage, local inflammation leads to the fourth stage of pseudocapsule formation and lesion maturation as the body attempts to sequester the fluid-filled space.

A: Normal layers of skin, tissue and bone.

B: Shear forces lead to the separation of superficial and deep fascial layers.

C: Fluid extravasation from injured vasculature leads to a haemolyphatic collection within the created space. (3)

Patient journey

As a result of the collision, the cyclist sustained an impact on his left lateral hip. Some pain is observed at the time, but otherwise, there are no immediate concerns about an acute injury. No other significant injuries were reported. After 5 days, there is increasing tenderness over the lateral aspect of the left hip with a considerable swelling that the cyclist can self-palpate.

Upon clinical examination, there is a complete and pain-free range of motion of the affected hip. With closer inspection, there is a visible swelling over the lateral hip in the greater trochanter region, and a soft cystic-like swelling accompanies this on palpation. Additionally, the overlying skin has moderate bruising, which extends a short distance distally from the swelling. Finally, there is moderate tenderness over the greater trochanter.

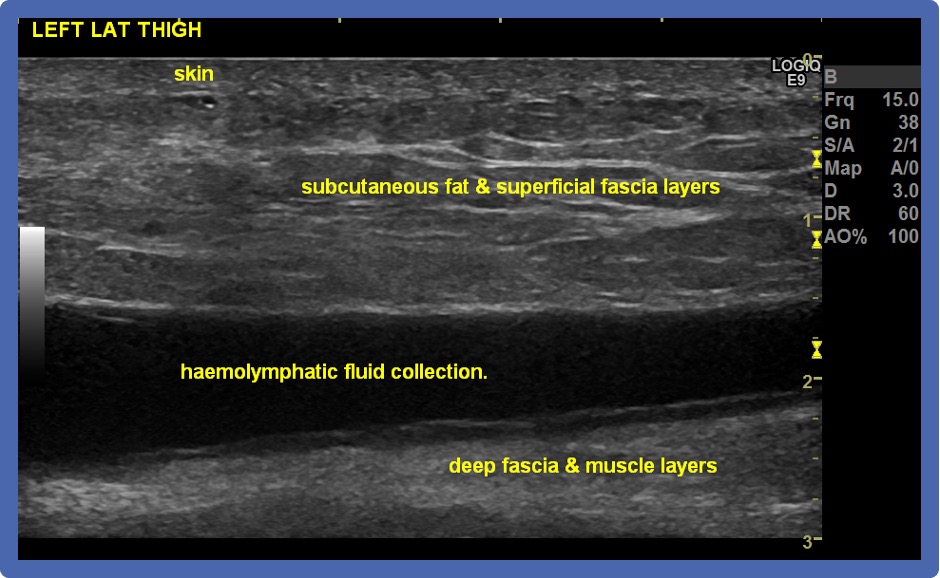

A diagnostic musculoskeletal ultrasound scan is performed. An anechoic (dark) lesion is identified on both longitudinal and transverse ultrasound imaging—the dimensions of the lesion measure several centimetres in craniocaudal length and width. The lesion is deep to the subcutaneous fat and above the underlying muscle later- there is compressibility with probe pressure. No doppler activity is seen within the fluid collection, and there are no sinister features to suggest a malignant space-occupying lesion. No bony abnormality of the greater trochanter is seen. A diagnosis of Morel-Lavallee lesion is made.

Diagnosis

History and Examination

- History of trauma:

- Lesions typically occur during falls and blunt trauma, but post-operative cases following liposuction have also been reported. (2) MLL often presents soon after the inciting traumatic event, although some patients may have a delayed presentation.

- The patient may not always be symptomatic.

- Localised tenderness:

- In general, a MLL can result in localised tenderness with discomfort due to the pressure effect of the large volume of serosanguinous fluid within a well-defined space.

- The most common location over the lateral hip and greater trochanter can make side-lying particularly difficult and painful, resulting in sleep interruption.

- It may be necessary to consider an aspiration of the fluid collection that can provide significant symptom relief.

- Swelling:

- Patients usually present with a gradually increasing compressible and fluctuant swelling that may or may not be painful.

- Bruising:

- Chronicity of events and the composition of the components within the lesion will determine the outward appearance upon examination.

- This can take several days to develop, thus causing prolongation in the time taken to reach a diagnosis and consequently a delay in treatment.

- Overlying soft tissue infection and/or fracture:

- MLLs are frequently found in polytraumatised patients as a subsequent consequence of the injury mechanism.

- The absence of prompt diagnosis and treatment may lead to a secondary infection, e.g. cellulitis.

- These complicating factors will largely govern the choice of treatment.

Investigations

Diagnosis is achieved by a comprehensive history and physical examination, alongside imaging modalities, typically ultrasound and/ or MRI. (3) MRI may be used when there is a lack of soft tissue definition on the ultrasound.

On ultrasound, there is an elevation of the subcutaneous fat layer and superficial fascia layers from the deep fascia, causing a fluid collection, which is shown as an anechoic (dark) lesion. Other ultrasound features may include the absence of flow on a colour doppler, and chronic lesions may show a hypoechoic capsule.

Differential diagnoses include necrotic soft tissue tumours and bursitis. Undesirable consequences can occur from delayed diagnosis and improper management, including infection, pseudocyst formation, and cosmetic deformity. (3)

Classification

Six distinct MLL patterns have been described. Lesion age and MRI imaging are used to distinguish each type.

Type 1: Simple seroma.

Type 2: Subacute haematoma.

Type 3: Mature organised haematoma.

Type 4: Closed fatty laceration complicated by perifascial dissection.

Type 5: Perifascial nodular lesion.

Type 6: Infected lesion with sinus tract, septations and capsular formation. (5)

How about the management of MLLs..?

Keep your eyes peeled for part 2 next week, where we will hear more about the management of these injuries!

____________________

Authors:

Richard Seah1,2,3, Michael Burdon1, Petros Akin-Nibosun4, James Thing1,5,6, Anthony Waring1,7

Affiliations:

1Pure Sports Medicine, London, UK

2Institute of Sport, Exercise & Health (ISEH), London, UK

3Royal National Orthopaedic Hospital NHS Trust, Stanmore, Middlesex, UK

4Medway Maritime Hospital, Medway NHS Foundation Trust, Gillingham, Kent, UK

5One Welbeck, London, UK

6The Joint Injection Clinic, London, UK

7Fortius Clinic, London, UK

Correspondence to:

Dr Richard Seah, Pure Sports Medicine, Canary Wharf, London E14 4QT, UK; rick.seah@puresportsmed.com

References:

- Morel-Lavallée VAL: Decollements traumatiques de la peau et des couches sous jacentes. Arch Gen Med. 1863;1:20-38, 172-200, 300-332

- Diviti S, Gupta N, Hooda K, Sharma K, Lo L. Morel-Lavallee lesions-review of pathophysiology, clinical findings, imaging findings and management. Journal of clinical and diagnostic research: JCDR. 2017 Apr;11(4):TE01.

- Scolaro JA, Chao T, Zamorano DP. The Morel-Lavallée lesion: diagnosis and management. JAAOS-Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2016 Oct 1;24(10):667-72.

- Vanhegan IS, Dala-Ali B, Verhelst L, Mallucci P, Haddad FS: The Morel-Lavallée lesion as a rare differential diagnosis for recalcitrant bursitis of the knee: Case report and literature review. Case Rep Orthop 2012; 2012:593193.23320230

- Suzuki T. Postoperative surgical site infection following acetabular fracture fixation. Injury 2010;41(4):396-399.20004894

- Nickerson TP, Zielinski MD, Jenkins DH, Schiller HJ. The Mayo Clinic experience with Morel-Lavallée lesions: establishment of a practice management guideline. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2014; 76:493–7.

- Bansal A, Bhatia N, Singh A, Singh AK. Doxycycline sclerodesis as a treatment option for persistent Morel-Lavallée lesions. Injury. 2013 Jan 1;44(1):66-9.

- Figure 1 created by Biorender.com