An overview of the quality and potential to promote behaviour change of the most downloaded Apps for people with one or more chronic conditions

We have a problem…

Osteoarthritis, hypertension, type 2 diabetes, depression, heart conditions, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease affect millions of people around the world, often co-occur (i.e., multimorbidity) and cause physical and mental impairments. 1 2 Compared to people living without medical conditions, people with one or more chronic conditions have poorer physical and mental health, 3are more likely to die prematurely, and be admitted to and have an increased length of stay in hospital.4 5 This is also associated with increased health care cost and health care utilization.6

A possible solution…

A healthy lifestyle is associated with up to 6.3 years longer life for men and 7.6 years for women with one or more chronic conditions.7 Mobile Applications (Apps) may improve the lifestyle of patients with chronic conditions, for example, through personalised self-monitoring, goal setting and behaviour change (e.g., increase physical activity) available anytime and everywhere.8 9 This topic has been the focus of recent research with promising results.10 However, although widely used (in 2019, more than 204 billion apps were downloaded)11 the quality (e.g., engagement and functionality), content and potential for behaviour change of the Apps is still unclear.12 13 This can compromise user lifestyle and, at worst, their health and safety.

What we did…

- We performed a systematic search, in the App Store and Google Play, of health Apps targeting lifestyle behaviours such as physical activity and diet, directed at patients with one or more of the following conditions: osteoarthritis of the knee or hip, heart conditions (heart failure and ischemic heart disease), hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and depression.14

- We assessed their quality and potential for behaviour change of the free content of the Apps, using the Mobile App Rating Scale (MARS-23 items)15 and the App Behavior Change Scale (ABACUS 21 items)16, respectively.

What we found…

- Overall, Apps for patients with a chronic condition or multimorbidity appear to be of acceptable quality but with a low-to-moderate potential for behaviour change.

- Apps for depression tended to have the highest quality, while Apps for osteoarthritis tended to have the lowest quality.

- Apps for patients with multimorbidity tended to have the highest potential for behaviour change, while Apps for osteoarthritis tended to have the lowest potential for behaviour change.

- Self-monitoring of physiological and behavioural parameters such as tracking medication intake, step counts, and diet were the most common features of the Apps.

- Most of the top-rated and most downloaded Apps for patients with a chronic condition or multimorbidity are not completely free.

Take home message

We suggest researchers:

- To develop and evaluate Apps with both high quality and potential for behaviour change.

We suggest patients and clinicians who would like to use Apps for managing chronic conditions:

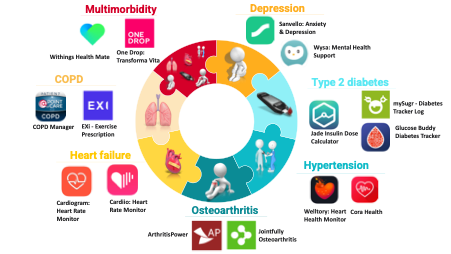

- To use and recommend Apps with higher quality and potential for behaviour change (Figure 1)

Figure 1 – Highest rated quality Apps and potential for behaviour change. - To use and recommend Apps based on the patient skills, needs and preferences.

Authors and Affiliations:

Bricca A1,2, Pellegrini A 1,2, Zangger G 1,2, Ahler J 2, Jäger M 1,2, Skou ST1,2

1 Research Unit for Musculoskeletal Function and Physiotherapy, Department of Sports Science and Clinical Biomechanics, University of Southern Denmark, 5230 Odense M, Denmark

2 The Research Unit PROgrez, Department of Physiotherapy and Occupational Therapy, Næstved-Slagelse-Ringsted Hospitals, Region Zealand, 4200 Slagelse, Denmark

Corresponding author

Alessio Bricca, abricca@health.sdu.dk, +45 65 50 95 10

Research Unit for Musculoskeletal Function and Physiotherapy, Department of Sports Science and Clinical Biomechanics, University of Southern Denmark, 5230 Odense M, Denmark.

The Research Unit PROgrez, Department of Physiotherapy and Occupational Therapy, Næstved-Slagelse-Ringsted Hospitals, Region Zealand, 4200 Slagelse, Denmark.

Competing interests

STS is the founder of the non-for-profit initiative Good Life with osteoArthritis in Denmark (GLA:D), implementing evidence-based clinical guidelines for patients with knee and hip osteoarthritis in clinical practice. STS is currently funded by a program grant from Region Zealand (Exercise First) and two grants from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program, one from the European Research Council (MOBILIZE, grant agreement No 801790) and the other under grant agreement No 945377 (ESCAPE). AB and MJ are postdocs in the MOBILIZE project (funded by the European Research Council, Næstved, Slagelse and Ringsted Hospitals’ Research Fund and The Association of Danish Physiotherapists Research Fund). The funding sources were not involved in any aspect of this work other than to provide funding. The authors declare to have no financial conflicts of interest.

References

- Bayliss EA, Bayliss MS, Ware JE, Jr., et al. Predicting declines in physical function in persons with multiple chronic medical conditions: what we can learn from the medical problem list. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2004;2:47. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-2-47 [published Online First: 2004/09/09]

- Diseases GBD, Injuries C. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 2020;396(10258):1204-22. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30925-9 [published Online First: 2020/10/19]

- Ioakeim-Skoufa I, Poblador-Plou B, Carmona-Pirez J, et al. Multimorbidity Patterns in the General Population: Results from the EpiChron Cohort Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020;17(12) doi: 10.3390/ijerph17124242 [published Online First: 2020/06/18]

- Menotti A, Mulder I, Nissinen A, et al. Prevalence of morbidity and multimorbidity in elderly male populations and their impact on 10-year all-cause mortality: The FINE study (Finland, Italy, Netherlands, Elderly). J Clin Epidemiol 2001;54(7):680-86. doi: Doi 10.1016/S0895-4356(00)00368-1

- Vogeli C, Shields AE, Lee TA, et al. Multiple chronic conditions: Prevalence, health consequences, and implications for quality, care management, and costs. J Gen Intern Med 2007;22:391-95. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0322-1

- Soley-Bori M, Ashworth M, Bisquera A, et al. Impact of multimorbidity on healthcare costs and utilisation: a systematic review of the UK literature. Br J Gen Pract 2021;71(702):e39-e46. doi: 10.3399/bjgp20X713897 [published Online First: 2020/12/02]

- Chudasama YV, Khunti K, Gillies CL, et al. Healthy lifestyle and life expectancy in people with multimorbidity in the UK Biobank: A longitudinal cohort study. PLoS Med 2020;17(9):e1003332. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003332 [published Online First: 2020/09/23]

- Direito A, Dale LP, Shields E, et al. Do physical activity and dietary smartphone applications incorporate evidence-based behaviour change techniques? BMC Public Health 2014;14:646. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-646 [published Online First: 2014/06/27]

- Middelweerd A, Mollee JS, van der Wal CN, et al. Apps to promote physical activity among adults: a review and content analysis. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2014;11:97. doi: 10.1186/s12966-014-0097-9 [published Online First: 2014/07/26]

- Sandal LF, Bach K, Overas CK, et al. Effectiveness of App-Delivered, Tailored Self-management Support for Adults With Lower Back Pain-Related Disability: A selfBACK Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med 2021;181(10):1288-96. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2021.4097 [published Online First: 2021/08/03]

- Annie A. The State of Mobile in 2020: The Key Stats You Need to Know. Available at https://wwwappanniecom/en/ (2020), Accessed August 26, 2020

- Kao CK, Liebovitz DM. Consumer Mobile Health Apps: Current State, Barriers, and Future Directions. PM R 2017;9(5S):S106-S15. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2017.02.018 [published Online First: 2017/05/22]

- Byambasuren O, Sanders S, Beller E, et al. Prescribable mHealth apps identified from an overview of systematic reviews. NPJ Digit Med 2018;1:12. doi: 10.1038/s41746-018-0021-9 [published Online First: 2018/05/09]

- Bricca A PA, Zangger G, Ahler J J, Jäger M, Skou ST. The quality and potential of Apps to promote behaviour change in patients with a chronic condition or multimorbidity: A systematic search in App Store and Google Play. JMIR mHealth and uHealth:(forthcoming/in press).

- Stoyanov SR, Hides L, Kavanagh DJ, et al. Mobile app rating scale: a new tool for assessing the quality of health mobile apps. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2015;3(1):e27. doi: 10.2196/mhealth.3422 [published Online First: 2015/03/12]

- McKay FH, Slykerman S, Dunn M. The App Behavior Change Scale: Creation of a Scale to Assess the Potential of Apps to Promote Behavior Change. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2019;7(1):e11130. doi: 10.2196/11130 [published Online First: 2019/01/27]