A proposed holistic and interdisciplinary model of care

When it comes to musculoskeletal (MSK) injuries, most clinicians will be familiar with the acronyms ‘RICE, POLICE and even PEACE & LOVE(1)’, but how does knowing that help in the grander rehabilitation process? Whilst they may provide a structure for the acute management of MSK injuries, they are extremely limited in providing a blueprint that considers the broader and more holistic elements that affect patients’ recovery. From our own clinical and educational experiences, and in revising for various formal MSK qualifications from a range of sources, we found that each book/website/clinician has a different approach to MSK medicine, and they are often specific to the background and training of the author/practitioner. As a result, these approaches can often overlook potentially key factors that influence patients’ outcomes(2,4). Whilst each of us have our own specialist skills and scope-of-practice, we propose a holistic and multi-disciplinary model that all clinicians can use to guide their approach to MSK complaints, one that can be tailored to anyone, from sedentary patients to elite athletes.

What is the #DREAM approach?

As outlined in Figure 1, #DREAM refers to an acronym that encapsulates some of the key domains that clinicians should consider when seeing a patient with an MSK injury. Each injury will ‘have’ its own specific ‘#DREAM’, which in practice would be informed by scientific evidence, the experience of the practitioner and a multitude of patient-specific factors. The purpose of this blog is not to delve into the evidence behind individual components (e.g. the evidence supporting certain rehabilitation protocols) or to provide a guide to a certain pathology, but to provide a practical blueprint and a list of factors for practitioners to consider.

D: Diagnosis

In all cases, a thorough history and clinical examination should take place, cognisant of red-flags or significant pathology. Other factors that should be routinely considered include:

- Whether objective investigations are needed?

o Consider the pros and cons of clinical investigations such as bloods/imaging. Are you asking a specific clinical question, the answer of which will influence clinical care, or are you ‘fishing’ to see what you find? If the latter, what could be the impact of finding an ‘incidentaloma’ not related to the presentation (e.g. a degenerative meniscal tear in the knee), and how will you explain that to the patient?

- Whether there is a specific context to this injury? Is a reliable/definitive return-to-play (RTP) timeline needed (as is often the case in elite sport), and would investigations help inform that?

- The language and labels used – be aware of phrases that can catastrophise diagnoses(5) (such as ‘Wear and Tear/bone-on-bone’ etc.)

R: Risk Factors & Rehabilitation

Risk-Factors. Though you may be seeing the patient after the injury has occurred, remember that prevention is better than cure, and that this is a potential window for you to reduce the chances of them being affected again in future. Can you work out what factor(s) contributed to the injury in the first place and reduce the likelihood of this happening again? Is this the consequence of numerous factors coming together even to cause injury, where just one factor in isolation may not be enough to contribute?

- Are there any non-modifiable risk-factors at play (age, history of previous injury etc)?

- Has there been any new unaccustomed activity or a sudden change in the level of activity (e.g. moving home and lifting lots of boxes etc in cases of shoulder pain)?

- Was this a ‘training error’ relating to load, a change in playing surface, a change in their S&C programme etc.?

- Is there a potential technique or equipment issue – are the coaches able to pinpoint anything?

- Were they on a programme that is too ‘aggressive’ for their ‘training age’?

- Think big-picture – could there be something else going on – RED-S, over-training, an undiagnosed medical condition, mental health issues etc?

Rehabilitation. Rehabilitation shouldn’t just refer to a one-off prescription of exercises. Adopt a biopsychosocial interdisciplinary approach to patient recovery that utilises various skill sets and backgrounds to help maximise the chance of good outcome. Some tips:

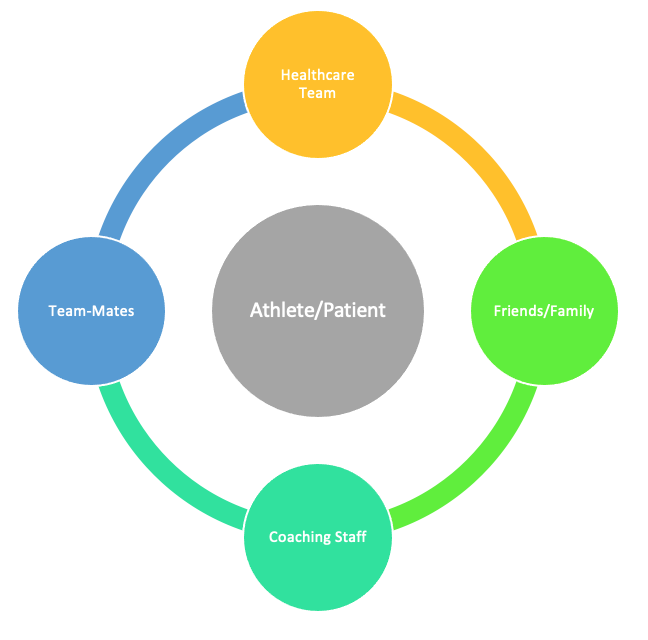

- Consider whether the patient wants to involve the wider support team (coaches, team-mates, parents etc) – but ensure the patient is in the ‘hub of the wheel’, and others form the ‘spokes’

Figure 2: ‘Hub and Spokes’ model - Draw a rehabilitation continuum, and signpost to the stages outlined below. If there has been a delay in the patient coming to see you, establish where they are on this timeline already, and ensure that the patient understands the fluid nature of the continuum and the criteria to progress through the stages.

- Early: RICE/POLICE/PEACE & LOVE etc – choose whichever you prefer (and can clinically justify). Offload or modify activities that provoke pain. Restore range-of-motion and improve proprioception. Avoid general de-conditioning.

- Middle: gradually increase the load on the injured tissue (& up the kinetic chain).

- Late: gradually increase the load on the tissue & gradually introduce loads that mirror the demands of their normal/pre-injury status. Work back from the patient’s ultimate goal, and base their rehab on this. Are there criteria that you should consider before they can be ‘cleared’ to go back to full function/play too?

- If in a sporting setting, are there things you could do to make them feel less isolated from their sport/activity throughout their rehabilitation process? As Phil Glasgow says, “Rehab is just training in the presence of injury”. Are there sport-specific skills they could integrate throughout the rehabilitation process, or can you give them a routine that mimics their life as an athlete?

E: Education

Consider this injury an opportunity for patients to increase their health literacy and empower them to take control and act as the main ‘driver’ of their rehabilitation process. This can be done by:

- Providing information relating to their condition in practical and understandable ‘chunks’. Can you get them to repeat back to you what they understand after your explanation?

- Considering and acknowledging the patient’s ideas, fears, expectations and goals, as well as their own personal/social situations. Provide reassurance where needed.

- Ensuring that the patient is happy with the role of pain during/after rehabilitation exercises, and the progressive element of the

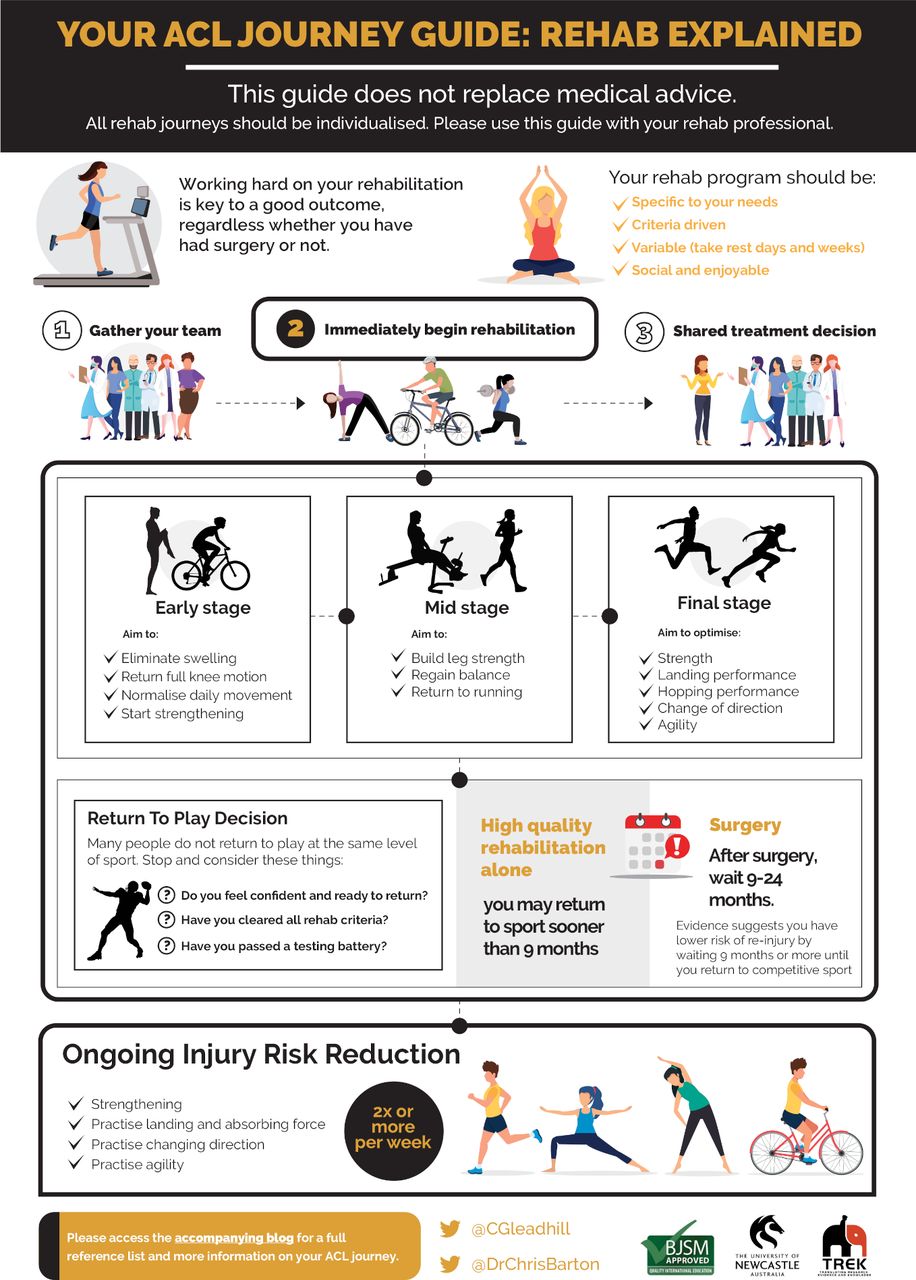

Figure 3. Infographic. ACL injury journey: an education aid | British Journal of Sports Medicine. Taken with permission of authors. process.

- Providing resources (such as that in Figure 2) that patients can refer to throughout their ‘journey’ (6)

A: Analgesia & ‘Accessories’

Analgesia. The options are almost endless in some cases. Ensure you are in line with the relevant anto-doping codes, and consider the goal of the medication and prescribe holistically (considering wider issues with chronic NSAIDs and opioid use)(7)

‘Accessories’. These will depend on several factors (including cost, risks, and evidence), but can be useful in many contexts. Consider dotting these along the rehabilitation timeline as per the goal of the adjunct (examples provided below). Ensure that the patient is aware of the role of these and that these are not seen as ‘quick-fixes’. Don’t chase the 1% ‘marginal gain’ if you haven’t nailed the basics that contribute to 99%+ of the recovery (strength, load management etc)

- Early: Nutritional supplements & muscle stimulators etc. to reduce muscle atrophy; Splints; Injection therapies (PRP etc), Shockwave therapy

- Middle: Hydrotherapy/Alter-G machine to accurately control load

- Late: Sports Psychology input for return-to-play issues; Taping & Bracing

M: Maintain Physical Activity Levels and/or Fitness

Re-frame the injury in a way that highlights what they can still do. Highlight the importance of being/remaining physically active & optimise other lifestyle factors (e.g. diet, smoking, alcohol intake and sleep). Consider taking a ‘Motivational Interviewing’ approach or trial a ‘brief intervention’ if time-limited(8), and try to find ways to overcome patient-specific barriers. For athletes, highlight that this injury is an opportunity to improve in other areas (e.g., strength in other parts of the body, tactical awareness) and provide examples and opportunities for them to improve in these areas.

Summary

Between us, we have found that the #DREAM model, which embraces a holistic and multidisciplinary approach, works well both clinically (especially as a checklist in cases where rehab is not progressing as hoped), and as a revision guide for those pursuing MSK/Sports Medicine qualifications. We hope that this serves as a guide that brings together the expertise and perspectives of a number of disciplines, to inform the approach of all clinicians who work in MSK settings and ensure that patients receive the gold-standard level of care.

Authors & Affiliations:

Steffan Griffin (1,2), Roshan Gunasekera (3), Adam Virgile (4), Emily Ross (2), Aisling Byrne (2), Carles Pedret (5), Dane Vishnubala (6,7), Vicann During (8), Sharron Flahive (9), James Noake (8, 10), Katy Hornby (2), Lorenzo Masci (11,12)

- University of Edinburgh

- England Rugby

- University of Sheffield

- University of Vermont (USA)

- FC Barcelona

- University of Leeds

- Hull York Medical School

- London Irish RFC

- Stadium Sports Medicine, Sydney

- Pure Sports Medicine, London

- Onewelbeck, London

- ISEH, London

Twitter: @SteffanGriffin @Rosh_C_G @AdamVirgile @EmilyRossPhysio @carlespedret @danevishnubala @dacrylicious @SharronFlahive @DrJN_SportsMed @lorenzo_masci

Conflict of Interest: SG is a deputy editor (social media) at the BJSM

References

- Dubois B, Esculier J. Soft-tissue injuries simply need PEACE and LOVE. British Journal of Sports Medicine 2020;54:72-73.

- Truong LK, Bekker S, Whittaker JL. Removing the training wheels: embracing the social, contextual and psychological in sports medicine British Journal of Sports Medicine 2021;55:466-467.

- Marmot M, Wilkinson R. Social determinants of health.2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005.

- Truong LK, Mosewich AD, Holt CJ, et al. Psychological and social and contextual factors across recovery stages following a sport-related knee injury: a scoping review. Br J Sports Med 2020;54:1149–56.

- Friedman DJ, Tulloh L, Khan KM. Peeling off musculoskeletal labels: sticks and stones may break my bones, but diagnostic labels can hamstring me forever. British Journal of Sports Medicine Published Online First: 06 May 2021. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2021-103998

- Gleadhill CP, Barton CJInfographic. ACL injury journey: an education aid. British Journal of Sports Medicine 2021;55:697-698.

- Tucker H, Scaff K, McCloud T, et al. Harms and benefits of opioids for management of non-surgical acute and chronic low back pain: a systematic review British Journal of Sports Medicine 2020;54:664.

- GC V, Wilson EC, Suhrcke M on behalf of the VBI Programme Team, et alAre brief interventions to increase physical activity cost-effective? A systematic review British Journal of Sports Medicine 2016;50:408-417.