Part of the BJSM’s #KnowledgeTranslation blog series

The anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injury rate for athletes in girls’/women’s sport has not changed in over 20 years, and they remain 3-6 times more likely to experience this injury when compared with athletes in boys’/men’s sport.

Injury prevention research in this area has, to date, focused heavily on seemingly ‘sex-based’ differences between girls/women and boys/men to explain and try to prevent ACL injury. This work has focused particularly on biological factors, like anatomy (such as the shape of hips) or hormones (such as during the menstrual cycle), to explain why women and girls may be more susceptible to this injury.

Unfortunately, this approach has not been overly successful, with ACL injury rates remaining higher for athletes in girl’s/women’s sport. This has led to a general perception that athletes in girls’/women’s sports are innately more likely to get this injury, and for biological reasons largely out of our control.

We found it curious that this ‘biological’ narrative has become the widely accepted in injury prevention for athletes who are girls/women. Given the persistent disparity in ACL injury rates for girls and women, we wondered whether it was time to explore alternative paradigms that could help us conceptualise new ways to intervene in the injury cycle – one that may actually take steps towards reducing rates of ACL injury in future.

Why is this study important?

This study is important because it challenges the prevailing narrative that girls and women are simply more susceptible to injury due to their biology. Indeed, this perception is based in outdated perceptions of girls’/women’s bodies as being naturally more ‘risky’ or ‘fragile.’ We show that higher rates of ACL injury could be explained by considering how gendered environments place their bodies at greater risk.

How did the study go about this?

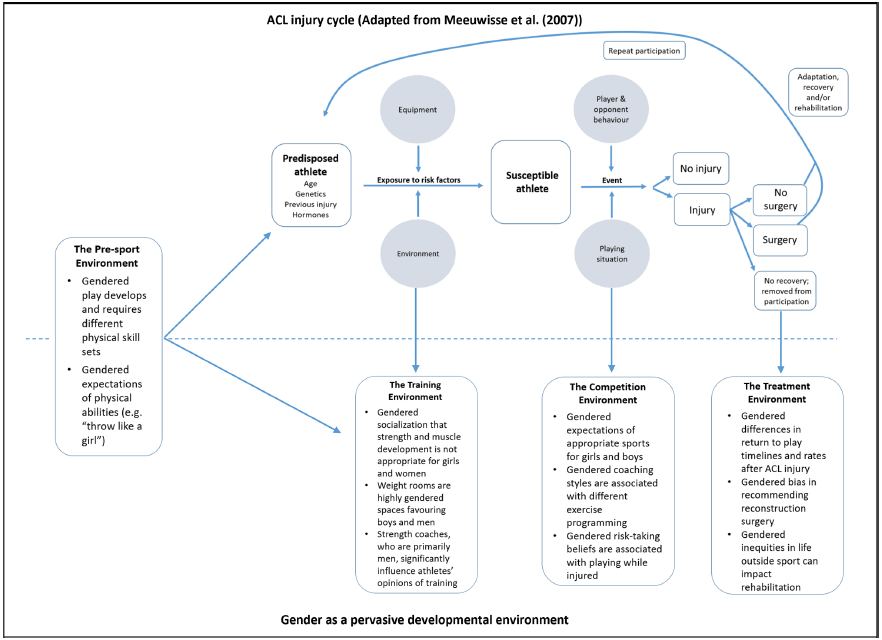

We first traced the ways in which ACL injuries have been researched to date. To do this, we looked at how risk factors, mechanisms of injury, injury models, and injury prevention programmes have been understood and developed. Crucially, in doing so we also paid attention to where biases in current approaches bleed through, such as the ways in which biology has been positioned as the sole, central cause of ACL injury to the exclusion of researching other social and environmental factors. We then discuss what those social and environmental factors might be, and make recommendations for future research and practice.

What did the study find?

Our research highlights the ways in which girls’/women’s lives are materially different from those of boys/men when it comes to physical activity and sport (and indeed many other domains across the lifespan), and how this might lead to differences in injury outcomes. We describe these conditions as social factors, or those cumulative environmental and societal experiences that are gendered in key ways.

Girls and women are not encouraged to be as active and physical as boys and men from the time that they are babies. This manifests in gender differences where girls/women and boys/men may develop and actually embody different skill sets (e.g. this is where the aphorism ‘throw like a girl’ is instructive).

Then, in training, competition, and treatment environments, girls’/women’s sports simply generally do not have the resources or expectations that men/boys sports do. Even where, on the surface, parity exists, the expectations and/or value of girls/women are often subtly—but sometimes explicitly—very different and much lower. A good example here is the recent NCAA March Madness championships in the US, where the men’s division was provided state-of-the-art strength training equipment whereas the women’s division was provided only one set of dumbbells. This example is very telling of what we expect of even elite athletes in women’s sports, and how gendered differences in sporting expectations and experiences may be subtle or overt, but still add up in disadvantaging girls/women. Different access to training, support, resources, and safety protocols; less media coverage and sponsorship; more harassment and abuse – these are all examples of gendered experiences or social factors that make participation in sport a very different one for women compared with men.

So for us, we wanted to show that girls’/women’s bodies aren’t naturally inferior, or weaker, or risky…but rather how they become so; how the gendered conditions of society and sport function to make girls’ and women’s bodies ‘risky’ and how this leads to disparities in ACL injury rates.

What are the key take-home points?

Key changes need to be implemented across women’s AND men’s sports – that’s how we make systemic changes. This is not only about targeting women’s spaces, but changing the norms (e.g., it’s not okay to say ‘girl push ups’ in women’s training environments or men’s training environments). Some examples of key pointers that can be taken up across all types of practitioners, from strength and conditioning coaches to rehabilitation specialists are:

- Language:

- Be specific about equipment and exercise names to avoid unnecessarily gendered terms.

- Example: There are no “women’s” and “men’s” barbells, there are only 15 kg and 20 kg barbells

- Focus on an athlete’s goals, performance gains, physical and mental health, not appearance.

- Example: Recognise an athlete’s gains in strength, rather than commenting on their physique (e.g., “toned,” “bulky”)

- Provide women role models in training spaces at all levels.

- Reflect on potentially taken-for-granted gender differences in expectations for women/men and/or programming for women and men. Critically assess why these differences are employed and what the potential consequences are.

- Consider how gendered roles and responsibilities (e.g. childcare, work hours) may interfere with an athlete’s progress in sport, rehabilitation, and recovery for both men and women.

- Evaluate the material aspects of athlete training and competition environments.

- Example: Are there gendered messages or imagery in weight-training spaces or locker rooms?

- Example: Are there material differences in how men’s vs. women’s training spaces are equipped or laid out?

- Be specific about equipment and exercise names to avoid unnecessarily gendered terms.

Authors and Affiliations:

Dr Joanne L Parsons – College of Rehabilitation Sciences, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada

Dr Stephanie E Coen – School of Geography, University of Nottingham, Nottingham, Nottinghamshire, UK

Dr Sheree Bekker – Department for Health, University of Bath, Bath, UK

Reference:

Parsons JL, Coen SE, Bekker S. Anterior cruciate ligament injury: towards a gendered environmental approach. British Journal of Sports Medicine Published Online First: 10 March 2021. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2020-103173